(Reprinted with permission from the Washington Post Book World, written by Jonathan Yardley.)

(Reprinted with permission from the Washington Post Book World, written by Jonathan Yardley.)

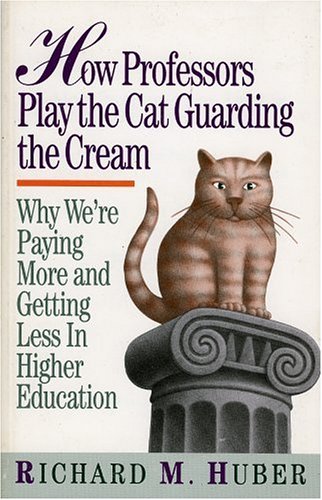

How Professors Play the Cat Guarding the Cream is not merely a critique of the hegemony of the professoriate, but a careful inquiry into how the campus differs from the rest of the world, most particularly the business world. It is a tough and at times a waspish analysis, but it is also fair and sympathetic; if anything, its irreverent fairness makes its criticism all the more penetrating.

Richard M. Huber knows whereof he writes. He has a standard-issue Ivy League education, he has been a college teacher and administrator, and he now runs State Department workshops for Foreign Service personnel. In the current dispute between traditionalists and radicals over various aspects of higher education he seems to side with the former, but he presents the radicals’ case thoroughly and dispassionately. He is, in any event, less interested in taking sides in an academic spitting match than in providing a guide so that “parents, students, business executives as trustees, alumni, legislators, and taxpayers can begin to master how universities work.”

They work in peculiar ways. “University culture,” Huber writes, “is filled with ironies,” many of which he explores in depth. A representative selection might include these:

-

“University presidents train to be managers by teaching and research.”

-

“The academic value of a credit earned by an undergraduate is the same whether taught by a full professor or a graduate student. It’s also the same price.”

-

“An increasing endowment does not reduce tuition, but inflates it.”

-

“A student at a private university can pay ten times more per course taught by a graduate student than a student at a community college pays while studying under a professor with a doctorate.”

-

“While the published research of scholars is rigorously evaluated for reliability, the undergraduate teaching of professors is seldom evaluated for the purposes of improvement.”

As these maxims suggest, Huber argues that the university is disorganized, inefficient, internally contradictory, and, so far as its teaching mission is concerned, unaccountable to anyone. It startles him that while undergraduates are quick to voice their grievances on social, political, and cultural matters, “a vigorous consumer movement has not emerged on campus.” Among the causes he cites for legitimate student complaints are: “class size, overenrolled required courses, incompetent academic advising, unavailable professors, disinterested part-time instructors and unintelligible teaching assistants”—problems that often become all the more pressing as universities become larger, richer, and more prestigious.

The blame for this, Huber says, rests largely with the faculty. To some degree he attributes it to plain human nature; a professor is as capable of venality and sloth as anyone else. But the greater difficulty is with the system itself, which balkanizes the campus into autonomous departments, places what are essentially administrative questions (i.e. appointments and tenure) in faculty hands, and affords far more prestige and financial reward to scholarship than to teaching.

Nothing in the structure of the university encourages service to the undergraduate, while everything encourages the single-minded pursuit of individual and departmental prestige. Universities compete against each other to accomplish the most celebrated research; the benchmark is scholarship, and it is to this that all universities devote the bulk of their time and resources.

The irony, Huber notes, is that “professors are hired as teachers but evaluated as scholars.” The person who enters the professoriate with hopes of a career in teaching quickly finds that a professional reputation cannot be made that way:

“Scholars want to be a member of a department with a national reputation for research.... Popular teachers do nothing to enhance the distinction of the department.... Indeed, ‘popular’ is not an accolade that resonates pleasantly in the academic ear. Popular novelists, poets, and composers can’t be good if the public likes them. Teachers who are popular are suspect for the same reason.”

The qualities that produce success in the business world are often useless, even counterproductive, in academia. Not merely is popular success held in contempt, but no training is provided for institutional—i.e. corporate—leadership. Among the faculty, respect for administrators is so low as to be nonexistent. Inefficiency and waste are as pandemic as in any government bureaucracy. Huber has some sensible proposals for combating this, none of them made “at the expense of achieving and sustaining a quality research reputation”—but he is enough of a realist to know that the chances of their acceptance are somewhere between slender and none. The cat guarding the cream has no interest in seeing it watered down to half-and-half.