|

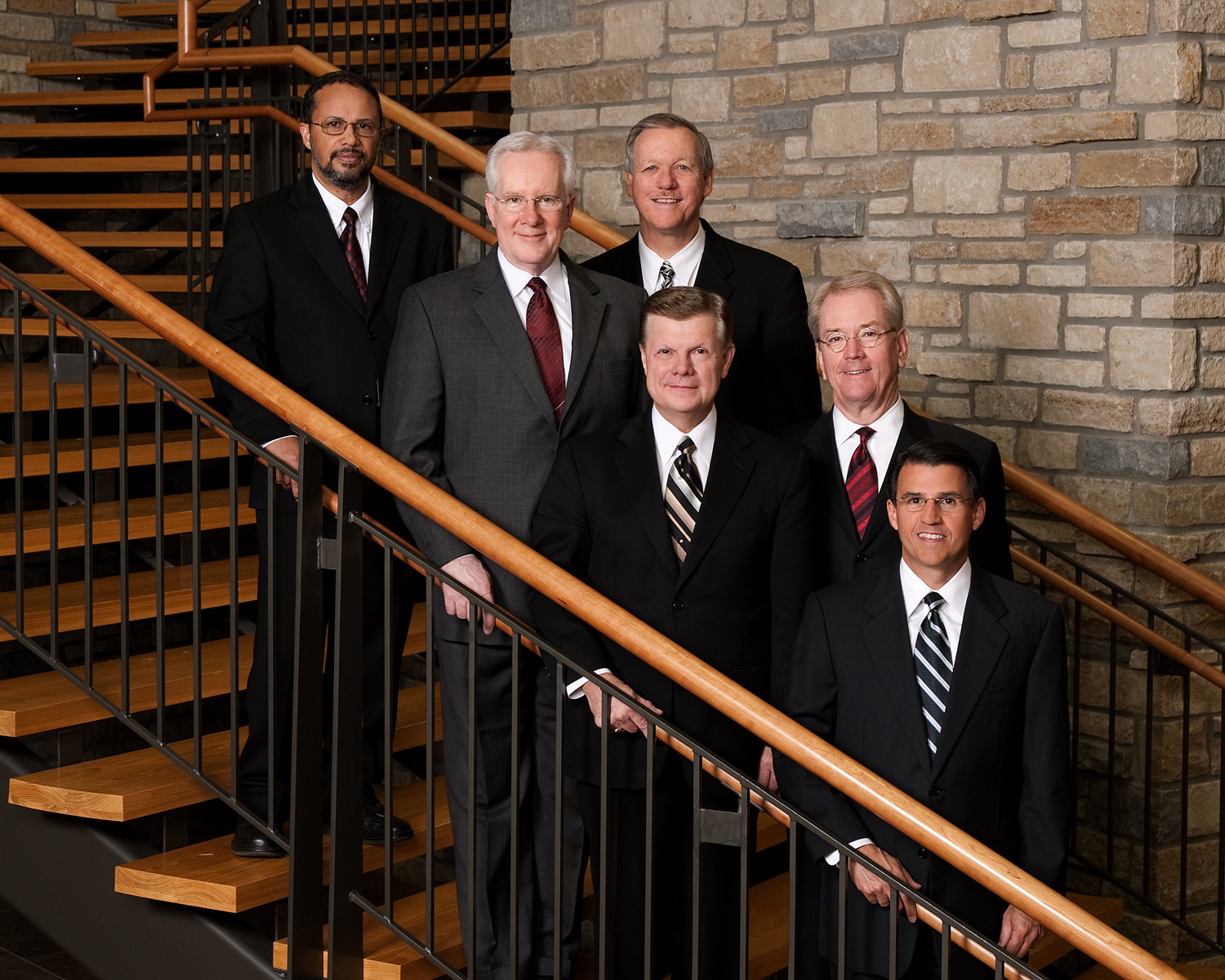

At St. Vladimir's Orthodox Theological Seminary, spring convocation brings bishops and other board members to campus. Here they gather with the school's administrators, including the dean, Archpriest John Behr (front, second from left) and the chancellor, Archpriest Chad Hatfield (front right).

Credit: Leanne Parrott |

Seven years ago, the Catholic archdiocesan seminary in Milwaukee found itself in an all-too-common situation, facing deficit spending that could not be sustained. Increased costs, declining numbers of seminarians, and the beginnings of the economic downtown were taking a toll on St. Francis de Sales, the nation’s third-oldest Catholic seminary. A decision needed to be made, and Archbishop Timothy Dolan — not the seminary’s board — was responsible for making it. (Dolan is now the cardinal archbishop of New York, but he was head of the Milwaukee archdiocese from 2002 to 2009.)

In the spring of 2006, Dolan announced that St. Francis would enter into an unusual collaboration with the nearby Sacred Heart School of Theology, run by the Priests of the Sacred Heart. Milwaukee archdiocesan seminarians would receive their academic formation at Sacred Heart while continuing to live at St. Francis, receiving spiritual and pastoral formation there.

Fast-forward five years. Cardinal Dolan, now head of the New York archdiocese, is spearheading another major decision about a seminary: St. Joseph’s Seminary in Yonkers. This time, he and two neighboring bishops are creating an unusual “interdiocesan partnership” that will share the responsibility for education and formation among three institutions — graduate-level programs at one site, undergraduate and “pre-theology” programs at another, and continuing formation programs at a third. (See 'A new "one-school model" for theological education in southern New York state' below.)

The New York interdiocesan partnership is overtly collaborative and includes a formal agreement among three bishops, but Cardinal Dolan’s earlier decision in Milwaukee emerged after much consultation with ministry partners, too. Though the responsibility for that decision was the archbishop’s alone, the idea actually came from a member of an ad hoc committee that Dolan had formed to advise him about the future of St. Francis de Sales Seminary. And while Dolan did not technically need approval from the seminary board, he sought the board’s input nonetheless.

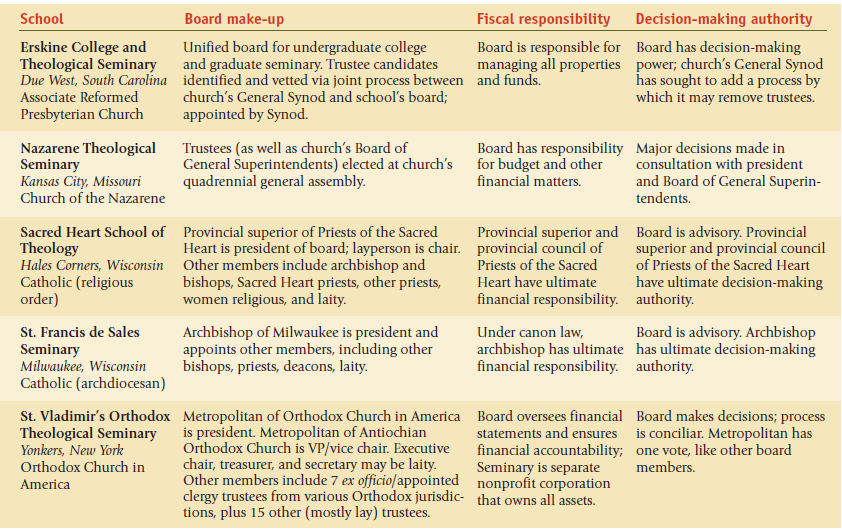

Major decisions, such as to close, merge, or otherwise reorganize a school, to hire or fire a president, or to make major financial or curricular changes, raise the question of who has ultimate responsibility. Within the world of higher education, the board of a school usually exercises this duty. But in some seminaries and theological schools, the board itself is subject to another authority, like a bishop or a council of church leaders. What are some of the challenges—or advantages—of having a board that works hand-in-glove with a church body? Is a board that doesn’t have the final word on some matters merely window dressing? Should boards try to be more independent? Grappling with questions like these can help a board understand its own role, and advance its institution’s mission, more effectively.

Who holds the reins? It’s not always an easy question to answer. For Roman Catholics, church law dictates that a bishop has ultimate authority over a diocesan seminary, even though the school may be separately incorporated, as in Milwaukee. For schools run by religious orders, the provincial superior (the head of a geographic region) or council of leaders has the final word.

Catholic seminary boards are advisory, except in the case of Catholic Theological Union (CTU), which is governed by a board of trustees from its sponsoring religious communities and at-large, lay trustees. But even at CTU, the board of trustees holds authority that is delegated by its corporate members — the heads of the religious communities that jointly own the school.

“Ultimately all authority in all Catholic seminaries rests with the highest authority, not with a lay board,” says Franciscan Sister Katarina Schuth, a professor at the Saint Paul Seminary School of Divinity of the University of St. Thomas. Schuth is author of several books on Catholic theological education, including Seminaries, Theologates, and the Future of Church Ministry (Liturgical Press, 1999).

“But that doesn’t diminish the board,” says Schuth, who advised Cardinal Dolan on his decision in Milwaukee. Schuth has served on nearly a dozen seminary boards. “Major issues are almost always well vetted and well considered through them,” she reiterates, “and their advice is honored. The bishop is there to hear what people are saying.”

|

| Priests of the Sacred Heart |

In the case of his decision to discontinue offering educational formation at St. Francis Seminary, Cardinal Dolan consulted extensively with the Catholic lay-people on the board as well as others with knowledge to contribute. “It was a thoroughly discussed issue,” says Schuth.

Father James Brackin, a Priest of the Sacred Heart who is former rector of Sacred Heart School of Theology, headed the ad hoc committee about the seminary’s future. He also recalls broad consultation about the decision. “Much to his credit, [Cardinal Dolan] really is that kind of person,” Brackin says. “I don’t think he ever thought he would make a unilateral decision.”

Bishop Donald Hying was dean of formation at St. Francis before being named rector of the school in 2007. (In 2011, Hying was ordained as a bishop and departed the seminary to become auxiliary bishop and vicar general of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee.) “The board certainly weighed in on it, but it was more honest to say, ‘This is what we have to do,’” says Hying. “They talked about how to implement it, but it would have been disingenuous to imply a different outcome.”

The final plan to discontinue academic formation at St. Francis also had to be approved by Sacred Heart School of Theology, where the St. Francis seminarians began taking their courses in 2006, even while they continued receiving spiritual and human formation on the St. Francis campus. Father Thomas Cassidy, current provincial superior of the Priests of the Sacred Heart, says that the faculty was consulted before the proposal was approved by both the school’s board and the provincial council.

In schools run by religious orders, the provincial superior is the “ordinary” — the authority with jurisdiction over the institution, just as a bishop has jurisdiction over a diocesan seminary. “Ultimately he and his council have final authority over all matters,” says Cassidy. “The provincial superior will reserve certain powers to himself and his council such as, for example, the appointment of the rector or final approval of the budget upon the recommendation of the board.”

This is a reflection of the Catholic theology of a hierarchical church. “That means people in authority are invested with the spiritual responsibility and canonical authority to exercise that leadership,” explains Bishop Hying. “The Catholic church is not a democracy. But the goal is to work with consensus, so advisory bodies do have a voice.”

Hying says he can’t think of a time when the seminary board and archbishop didn’t come to consensus. But that doesn’t mean that the board is a rubber stamp. Board deliberation, he says, helps those who have authority to make informed decisions “without the power politics of a divided or factionalized board.”

The Church of the Nazarene may not have bishops, but “we probably have considerable affinity with Roman Catholics in our theological understanding of authority,” says Dr. Jeren Rowell, board chair at Nazarene Theological Seminary in Kansas City, Missouri.

“We don’t have a representative, Presbyterian form of governance,” he says about the denomination, which is part of the Wesleyan-Holiness tradition. “We have a strong sense of superintendency that puts significant authority in leaders having the theological vision of the church.”

For Nazarene Seminary, this translates into a close relationship between seminary’s board and the denomination’s leaders, especially the church’s six-member Board of General Superintendents. This connection of seminary with denominational leadership is part of the school’s 67-year history. It was founded as a “service” of the church, Rowell explains, and it continues to receive significant denominational funding, though that has diminished in recent years. The seminary’s board members, and the Board of General Superintendents, are elected at the denomination’s quadrennial General Assembly.

Rowell describes decision making for the seminary as “collaborative and collegial” and notes that such a relationship can prove advantageous, as it did in the school’s 2011 presidential search, when Dr. David Busic first declined the position when it was offered to him.

|

When David Busic initially declined the offer of the presidency of Nazarene Theological Seminary, the denomination's Board of General Superintendents (above) asked him to reconsider. "We have a strong sense of superintendency that puts significant authority in leaders having the theological vision of the church," says the seminary's board chair, Jeren Rowell.

Credit: Church of the Nazarene |

Busic had been chosen by the board in an election from an approved list of nominations by the Board of General Superintendents, which had been created after the superintendents met with the board search committee. He was pastor of one of the largest Nazarene congregations in the United States, and after he declined, the board reconvened to consider its next steps. Meanwhile, the superintendents called on Busic to reconsider, Rowell says. Months after the initial call, he accepted.

The denominational leaders were a “significant voice,” Rowell says, and their intervention “absolutely” did help reassure Busic of their confidence and support. “I can see how it may look controversial from the outside,” Rowell says, “but we understand it as a process of discernment.”

The process is similar for appointing faculty. The Board of General Superintendents must approve any candidates proposed by the administration and board—and there have definitely been differences of opinion between the two groups.

“The purpose is to ensure theological integrity,” says Rowell. “From a denominational perspective, it works well for them to exercise discernment over who is chosen as faculty. They want to have real confidence that the people teaching at the seminary are going to be shaping faithful pastors for the Church of the Nazarene.”

Rowell says he and other board members don’t see this lack of board independence as problematic. “What makes it work is the relationship we have. Nobody at the table is a stranger. We’re all friends. In a denomination of 2.2 million, leadership gets to be a small group of folks. We have an essential relational trust that makes that work.”

When denominational leaders have significant authority, however, the building and nurturing of those church-board relationships can be challenging. The recent controversies at Erskine College and Theological Seminary highlight the potential for tension, especially when relationships between denominations and schools change over time.

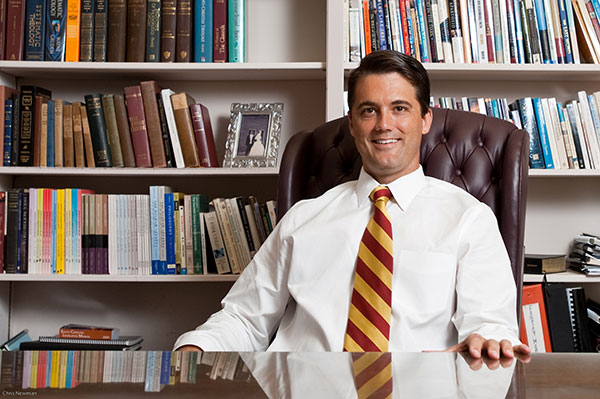

Smoothing such bumps requires constant attention to trust and relationship building, which can be difficult, emotional work, says David Norman, president of the South Carolina school, which is affiliated with the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church. “Not only is the potential for misunderstanding high, but the pain of misunderstanding is great,” he says.

Norman calls the denomination–seminary conflict that predates his presidency an “earthquake” with aftershocks that still reverberate today. Just this past spring and summer, the church governing body and the school’s board clashed over the procedure for removing individual board members for cause. And there was disagreement about whether the denomination’s influence will cause problems for accreditation.

|

| Erskine College and Theological Seminary |

Those are just the latest in a series of struggles over the university and seminary. Concerns about doctrinal purity, financial management, and cronyism at the school had surfaced at the denomination’s annual synod meeting for years, resulting in the creation of a special commission to oversee Erskine’s mission in 2010. The commission’s report raised issues ranging from the size of the board and ideological divisions within it, to negligence in overseeing faculty and a “culture of intimidation” on campus. Of special concern was the upcoming presidential search.

At the first emergency meeting in the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church’s 200-year history, the General Synod voted in 2010 to dissolve the college and seminary board, replacing it with an interim board. That controversial decision was never implemented, in part because of a since-dropped lawsuit by some trustees and alumni, and the board and synod eventually agreed to call Norman as president—a relative outsider and only 34 at the time of his appointment, he’s a graduate of Auburn University, Reformed Theological Seminary, and the University of Edinburgh.

While the conversation continues over Erskine’s governance structure—particularly the power to appoint and remove board members—the church’s General Synod did vote this June to continue its financial support of the college. Yet some critics from within the church are calling on the denomination to break official ties with the college, including financial ones. (Ironically, Erskine is named for Scottish minister Ebenezer Erskine, who led a group that seceded from the Church of Scotland in the early 18th century.)

Norman believes maintaining the relationship is crucial, though countercultural, given that many religiously affiliated liberal arts colleges have severed or marginalized their denominational affiliations in recent decades. “What we’re trying to do is a bit different, but more difficult,” he says. “But an organic, real relationship with the church makes for a better institution, both graduate and undergraduate.”

That one unified board oversees both the graduate seminary and the undergraduate liberal arts college only complicates matters. However, the structure reflects the school’s lack of belief in a sacred/secular split, says Norman. “Our ultimate mission is to equip students to flourish as whole persons. Some of those students are meant to do that as lay people, some as ministers. We believe in the great Protestant ideal of all truth being God’s truth and all work being God’s work.”

Likewise, Norman sees Erskine’s governance structure as particularly Presbyterian. “The whole idea of board governance has its roots in the presbyterian form of government. It’s a very Scottish thing to do,” he says. “We don’t have a bishop; an elder gets a same vote as a minister.”

It seems there are almost as many governance structures as there are denominations, and sometimes even unique arrangements within a religious tradition. Orthodox Christianity, with roots in various Eastern European and Middle Eastern homelands, is especially complex at the jurisdictional level, with bishops and metropolitans overseeing several national churches. When studying the Orthodox, it can be helpful to have both an atlas and a dictionary at hand—especially if you don’t know the difference between autocephalous and autonomous.

The Orthodox Church in America was founded by Russian immigrants to North America, and it is headed by a bishop with the title of metropolitan, who serves as president and chair of the board for all three Orthodox Church in America seminaries. From November 2008 until July 2012, this leader was Metropolitan Jonah, who was born James Paffhausen. (Paffhausen took the name Jonah when he became an Orthodox monk in 1995; Orthodox bishops do not use surnames.)

One of these seminaries is St. Vladimir’s in Yonkers, New York, which draws students from historically Russian congregations as well as from other Orthodox jurisdictions. Reflecting the diversity of its constituency, its board includes Russian, Greek, Serbian, and Syrian bishops, as well as priests, deacons, and lay members from the various Orthodox branches. All have voting rights.

As with other branches of Christianity, the seminary’s authority structure reflects the church’s theology. “The history of our church is conciliar, and the board works that way too,” says Anne van den Berg, a lay member of St. Vladimir’s board. “Unlike Catholicism, where the pope is the head of other bishops, our metropolitan is considered a brother bishop to other bishops, a ‘first among equals.’”

“So there is this tradition of conciliarity, coming together to make decisions, inspired by the Holy Spirit,” she says. “You see that carried over in the board. We work together with the metropolitan, who is always there at our board meetings.”

Van den Berg, who is also a member of the board of directors of In Trust, sees several positives to the arrangement, including direct communication between church authorities and the board. “It provides a very nice liaison from the church and more immediate feedback about whether we’re meeting the needs of the church,” she says. “The metropolitan is also very aware of what we’re doing, so there’s no ‘gotcha’ moment of something he wouldn’t have known about if he weren’t on the board.”

The board has normal fiduciary responsibility for the seminary and elects the administrators for the school, in consultation with the metropolitan. For example, five years ago the board came up with the idea to split the top administrative job into two equal positions—dean and chancellor. The system encourages consultation between the two leaders, both of whom are ex officio members of the board. Archpriest Chad Hatfield, the chancellor, oversees administration and operational duties. Archpriest John Behr, the dean, is responsible for academic and ecclesial matters.

“It’s a unique system that works well because we make it work,” says Hatfield, who compares it to the Byzantine symbol of the double-headed eagle. “It can be frustrating for me when I want to make a quick decision, and I’m not sure it’s a model for personalities who have clashed. But we’re happy with it.”

Around the same time, the board decided to create a new board leadership position—executive board chair— since the metropolitan always serves as both president and board chair. And the board is shifting to assume a greater role in advocacy and fundraising, Hatfield says.

The metropolitan reserves certain responsibilities to himself, such as presiding at the opening of graduation, at ordinations, and at major feast days, says Hatfield. But since he’s president of three seminaries, the metropolitan’s responsibilities encompass not only St. Vladimir’s but also St. Tikhon’s Orthodox Theological Seminary in eastern Pennsylvania and St. Herman Theological Seminary in Alaska. While Hatfield doesn’t see that set-up as having conflict-of-interest issues, he does wish it were a “tool for more cooperation.”

|

Archpriest Chad Hatfield is chancellor of St. Vladimir's Orthodox Theological Seminary. He says that his school's unusual administrative set-up "works well because we make it work."

Credit: Robin Hatrak |

But like all governance systems, the Orthodox model can be challenged by unforeseen circumstances. On July 6, 2012, Metropolitan Jonah, the head of the Orthodox Church in America, resigned from his post under fire, leaving the all three seminaries without a president and board chair. Later in the month, the Holy Synod of the Orthodox Church in America—the diocesan bishops in council, who comprise the “supreme canonical authority in the Church”—released a three-page letter in which they explained that they had asked him to resign because of poor judgment in addressing misconduct within the church.

There are clear limitations to a hierarchical model of governance. The Holy Synod’s letter itself indicates that “Metropolitan Jonah has repeatedly refused to act with prudence,” resulting in lasting damage to the church. Yet the bishops, acting in concert, were able to address the issues in a decisive fashion. Furthermore, even with the sudden resignation, the Orthodox seminaries were not left without a shepherd for long. Archbishop Nathaniel of Detroit, the locum tenens metropolitan of the Orthodox Church in America, stepped in as president and chairman of the boards of the three schools. And of course, each individual board provides continuity of leadership, even when the chair resigns.

One thing seems clear: Even in situations in which a theological school’s board is not the final authority, the board’s influence is critical. It’s up to the church authority, and the board itself, to work out its contribution— whether in sharing wisdom, functioning within a designated sphere of authority, or offering stability during a crisis—while navigating the tumult of real life.

A new “one-school model” for theological education in southern New York state

Cardinal Timothy Dolan, the archbishop of New York, and two of his neighboring bishops have created an unusual “interdiocesan partnership” among three institutions. Under a joint operating agreement, Dolan, along with Bishop Nicholas DiMarzio of Brooklyn and Bishop William Murphy of Rockville Centre, is implementing a plan that merges the faculties and student bodies of St. Joseph’s Seminary in Yonkers and the Seminary of the Immaculate Conception in Huntington.

The new plan involves more than one hundred seminarians from all three dioceses who will complete their graduate studies and formation at the Yonkers school, also called “Dunwoodie,” starting this year.

While graduate-level seminarians are living and studying at Dunwoodie, undergraduate- level seminarians and postcollege “pre-theologians” from the three dioceses will reside in the Cathedral Seminary Residence of the Immaculate Conception in the Douglaston neighborhood of Queens—the site of the Brooklyn diocese’s former Cathedral College, which closed in 1988. They will take at least some of their courses there as well.

Living in the communal residence, undergraduate- level seminarians will earn bachelor’s degrees, with at least a minor in philosophy, at St. John’s University in Queens or at other nearby Catholic colleges. At the same time, “pre-theologians” —college graduates taking prerequisite philosophy classes before they begin graduate- level studies for the priesthood— will earn two-year accredited master’s degrees in philosophy through St. Joseph’s Seminary by taking graduate courses at the Douglaston campus. (A similar program for college and “pre-theology” students, formerly offered on the Dunwoodie campus, has now closed.)

Finally, several new programs will find their homes at the Seminary of the Immaculate Conception in Huntington, 40 miles out on Long Island in the Diocese of Rockville Centre. After a “teach-out” during which current students finish their coursework, Immaculate Conception will no longer offer post-graduate degrees for laity and clergy candidates nor seminary training leading to ordination—in Catholic parlance, it will no longer be a “theologate”—and its state charter as an independent degree-granting institution will be suspended.

Instead, the campus will become the Immaculate Conception Center for the New Evangelization, a retreat and conference facility operated by the diocese. The Huntington campus will also become a branch campus of St. Joseph’s Seminary, where lay students and permanent deacon candidates will earn master’s degrees in theology and pastoral studies under the aegis of St. Joseph’s.

The new Immaculate Conception Center will also host the Sacred Heart Institute for the Ongoing Formation of Clergy, yet another entity within the three-diocese partnership, which offers unaccredited orientation programs for parish priests, permanent deacons, newly ordained clergy, and international priests.