Photo illustrations by Thomas Allen

A multiyear project is opening fresh conversations about the current moment and the future of theological education.

This essay is the fourth in In Trust magazine’s partnership with the Theological Education Between the Times project, based at the Candler School of Theology of Emory University and funded by Lilly Endowment Inc. Gathering diverse groups of people for conversations about meanings and purpose, the project begins with the understanding that theological education is undergoing profound change, and aims to stimulate conversation about the ends of theological education that can orient later conversations about its means.

The author, Keri L. Day, Ph.D., is a member of the faculty at Princeton Theological Seminary; this essay is from her book for the Between the Times series, Notes of a Native Daughter: Testifying in Theological Education.

As a Black woman scholar, I feel anger, disappointment, and heartache with ongoing forms of structural racism in theological education. So many theological institutions imagine themselves as doing anti-racist work. They form anti-racist committees to formulate institutional strategies geared toward racial diversity. They appoint task forces to oversee the conceptualization and implementation of multicultural programs. Theological institutions do cluster hires of faculty of color without any institutional investment related to retention and tenure. They reform curriculum while giving little attention to the cultures of whiteness that pervade institutional policies and practices. Black faculty members feel the burdens of such institutional posturing and lack of accountability to what’s needed for real transformation. Theological schools must acknowledge and address the psychological carnage Black faculty experience in the wake of institutional racial disenfranchisement and violence.

My book, Notes of a Native Daughter: Testifying in Theological Education, seeks to unearth this dilemma for Black faculty and students in the theological academy. I tell my personal story about this dilemma. I encounter a paradox: As a Black woman scholar, I am both an insider and outsider within theological education. In the 1940s and ’50s, writer and activist James Baldwin spoke as a “native son,” as one who can rightly claim himself as an inheritor of and contributor to the American tradition yet is treated as insignificant and of little worth. Similarly, African Americans are nurtured inside of and contribute to theological contexts that nevertheless treat them as marginal and peripheral, pointing to the unending contradictions experienced by Blacks in theological institutions. I testify about my experiences of being a native daughter as a way to not only illuminate the intersectional forms of racism that continue to plague the theological academy but also demonstrate how persons like me continue to make theological spaces creative, dynamic and life-giving. We continue to make these spaces “home.”

Let me offer an example. In the book, I write about Black theologian James Cone’s work and commitments to exposing whiteness and structural racism as sin. On the one hand, James Cone’s theology of Black liberation has been central to the theological academy’s ability to see how anti-Black racism grounds white theological projects and the broader white church. Cone’s intellectual corpus testifies to the harm Black communities continue to endure underneath white supremacy. In many theological schools, Cone’s theology has led to a revamping of curriculum as well as a focus on racial justice at an institutional level. Some schools now require students to take courses in liberationist theology and other discourses that focus on structural racism. In so many ways, Cone has been a major voice in the shaping of theological education. Many students arrive at seminaries and divinity schools and experience intellectual and spiritual refuge when reading and discussing Cone’s work. Cone’s contributions to theological education allow Black students (and many non-Black students) to find theological voice and vocational identity. Cone’s ongoing legacy through his work makes theological contexts “livable” for many students of color.

… testifying was a way of showing we had overcome those things that attempted to assault and destroy our minds and even ability to hope.

However, even as Cone’s work had undoubtedly contributed to the trajectory of theological scholarship, theological perspectives like Cone’s theology are yet marginalized, seen as “cultural insights” instead of theology proper. For instance, Black faculty are often met with questions from white students on how Black theological thinkers like Cone relate to them. They want to know how Cone is relevant to their social context and church culture. Of course, Black faculty are baffled by such white ignorance and privilege. Such students assume that Black theologians have nothing to say to their theological traditions and cultural contexts. Even more problematic, these students assume that Aquinas or Barth are enduring thinkers who speak to all cultures and people across time, place, and space. Although Cone directly calls upon white communities to confront and remedy the oppression that their communities help to create and support, many white students treat Cone as irrelevant, as a cultural unicorn that has no bearing on their theological journey.

Black faculty and students experience themselves as insiders and outsiders of theological education. And theological institutions must acknowledge this paradox to transform the structures, policies, and institutional ethos of their schools.

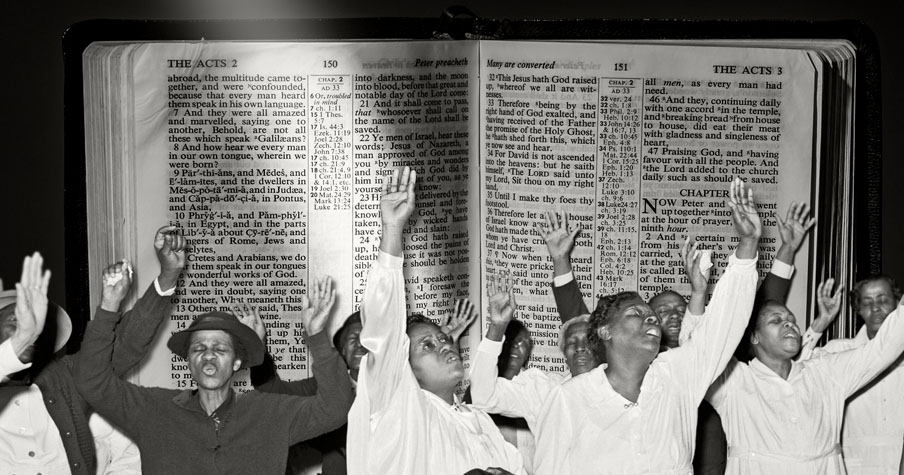

I testify about being an insider and outsider in the theological academy. I also hope this text invites other Black faculty (and faculty of color more broadly) to testify. Testifying is a familiar mode of speech for me. In my Pentecostal church in my hometown, testimony service sat at the center of our worship experience. Testimony service was verbal and demonstrative, a way of proclaiming the truth of our experiences as we waited for the liberating power of the Spirit. What was powerful about testifying was how it was a collective act. Although the individual speaker testified about God’s goodness amid their daily activities, the speaker’s testimony was also about collective awakening and affirmation. One’s testimony was met by affirmation within the community and the truths the speaker spoke about God became knowledge of who we were as a community. If God blessed the speaker to stay healthy, we received this word as God’s will for all of us. Testifying offered a different way of experiencing divine presence – God was experienced in community. Most importantly, testifying was a way of showing we had overcome those things that attempted to assault and destroy our minds and even ability to hope. We would not be silent. We would testify.

Black faculty and students must testify. Testify to the ongoing intellectual assault they endure for refusing to conform to normative standards of teaching and scholarship. Testify to the micro- and macroaggressions they experience when politically confronting inequitable practices within white academic cultures. Testify to new worlds that await to be born beyond the racially traumatic and anxiety-inducing spaces of theological education. I recognize that for some Black faculty and students testifying comes at a cost. White structures within theological education can be violent. A Black faculty member might be denied tenure for challenging the administrative system. Black students might receive poor grades or be targeted by white professors and students for telling the truth about the racist character of the classroom. However, Black faculty members and students must testify and tell the truth about white structural violence they endure.

I also hope administrators and white faculty will listen and become undone by the frustrations and cries of native daughters and sons. I propose that theological institutions not only acknowledge and rectify the racial disenfranchisement Black faculty and students endure but also build educational ecologies where we truly desire to be in authentic community. In my estimation, part of knowing how to build just and caring educational ecologies involves listening to contemporary radical social movements oriented toward practices of gathering and inclusion. Perhaps, as native daughters and sons testify, theological institutions will listen and begin anew.

Find more at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology.