|

| From Psalm 133 |

There is a malaise that is pandemic—perhaps universal—among new seminarians, and I suspect that new seminary trustees are not immune to it.

It has to do with the school’s being a human community, replete with tangled relationships and populated with sinners. Consciously or unconsciously, people tend to arrive at seminary at least hoping for and at most expecting something different, something better, something purer.

Sometimes the malaise emerges when students arrive, sprouting from seeds sown earlier. Some students come wounded, seeking refuge, and are dismayed to learn that they share responsibility for community life. Some are touchingly young and idealistic and naive; occasionally one still appears who is shocked to hear a professor cuss. Some anticipate a rarefied life of the mind. Some expect more prayer, some expect more reverence, some expect more engagement with the broken world. In some the malaise develops more gradually—when they encounter the sheer nastiness that can pervade the politics of the academy, for example.

It plays itself out in all sorts of ways, too. Some new students leave noisily. Some stay and give in to whatever unhealthy acting out is in vogue: food, sex, and gossip are old standbys. Others stay, apparently with the intention of bringing everyone else to their level of misery.

The trustee experience is different, of course. The theological school is not the board members’ primary community. They don’t expect the board to be their family or their church. And for the most part, they have enough experience of human institutions—even churchly ones—to have appropriately low expectations of human behavior.

Still . . . I wonder if trustees’ souls don’t get weighed down, too. . . .

I didn’t start seminary with especially high expectations of community. For better or worse, my early formation was such that I got the point that being bright and pious wouldn’t necessarily make one happy in ministry right along with “Jesus loves me, this I know.” (It had to do with my home church’s all-out attack on a pastor who, granted that his interpersonal skills were less than polished, tried to be faithful—but that’s another story). And I admit I shook my head over my short-lived classmates who bolted in dismay, especially the one whose parting shot was a poem in the school newspaper about how the prevenience of grace means that God committed to loving the church before thinking about it. He was on to something there; I would have liked to see his pastoral mind develop.

Nevertheless, the particulars of life in that community wore me down. That’s not an indictment of my school. As I’ve already noted, it happens everywhere. But where it wore me down—and I’m guessing that I’m not alone here, either—was in my life of prayer. Without going into tiresome detail, even though I was always where I was supposed to be at chapel time, and even though I attempted conversation with God, the prayer got pretty terse. I didn’t have a great deal to say that wasn’t whiny, so I didn’t say a great deal. Over the course of a year or so, things got terribly quiet.

|

| From Psalm 180 |

By grace, it was also in seminary that I was introduced to the daily office. Not a particularly formal introduction, to be sure. It was in the days before the current spirituality boom. We were more or less expected at chapel every day before lunch, especially on Wednesday, when the Lord’s Supper was celebrated. Aside from that, we were on our own, spiritually speaking—except for a small group of students and the very occasional faculty member who kept a minimal schedule of morning, evening, and nighttime prayer in the chapel, praying each office once a week on different days to accommodate the widest possible circle of commuters. The prayers were no-frills, using the words in our denominational hymnal.

It saved my neck.

Partly it was knowing that I was praying with a community far larger than that of the seminary, one in which petty concerns were put into perspective, swallowed whole as a matter of fact. But more to the point, it was the constant, ongoing repetition of the psalms.

The psalms were the prayerbook Jesus used, of course—speaking of perspective. But what got me is the impossibility of reading over and over again through that range of human experience without connecting, without agreeing somewhere, without getting the conversation of prayer started again. “My bed is soaked with my tears and by the way, You know exactly why. . .,” and so on. And the constant round means more opportunities to connect, and so although I’ve maintained nothing like perfect adherence to the round of morning, noon, evening, and night prayer, I’ve tried. I’ve used who knows how many resources from all sorts of traditions, but it’s the continuity I’ve sought. And I’ve had arid times, but nothing like what seminary brought on.

An ongoing life of prayer requires three things: permission, structure, and encouragement. Here’s your permission. As for structure, look to your own tradition for a start, and to the psalms themselves. Boards can encourage their members by praying together, when they are together, with the rhythms of their meetings rooted in a rhythm of prayer. And that rhythm can be taken home, as a continuing connection to the task at hand, and to the Source of strength who makes it possible.

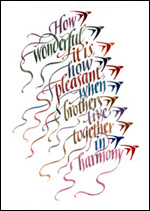

Illustrations by calligrapher Timothy R. Botts from The Book of Psalms,

(Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Wheaton, Illinois, 152 pages, $25) www.tyndale.com.

The language is that of the New Living Translation.