|

|

|

L. Gregory Jones, dean of the Duke University Divinity School, team-taught a university-wide seminar “The Geographies of Memory” with Karla Holloway, Duke’s dean of humanities and social sciences.

Photograph by Jim Wallace, courtesy of Duke University Photography

|

Imagine being a university student who reads an ad in the campus newspaper that’s so inflammatory and outrageous that you feel physically ill. Imagine you become angry enough to protest, demonstrate, occupy academic offices, and risk arrest to express your rejection of this affront to inexpressible core values. Now imagine being that same student and discovering that the local theological school is not only fully prepared to discuss the issue but has in place the leaders, the analytical framework, and the vocabulary to articulate a reasoned and compassionate response that is scripturally based.

This is no academic exercise. The student protest occurred in the spring of 2001, at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. And Duke University Divinity School provided the response that led to healing.

“Our situation was similar to the story in the Book of Daniel,” recalled Willie James Jennings, the divinity school’s senior associate dean. In that story “Daniel and three Hebrew boys who become men juxtaposed their wisdom with the wisdom of others.” (There’s also the bit about being thrown into the lion’s den, but one might as easily say it all boils down to being in the right place at the right time.)

When social provocateur David Horowitz of California submitted his incendiary denunciation of slavery reparations to fifty college newspapers, he had no idea where its publication might foment campus unrest. He could not have imagined that spontaneous student protest, university-wide disruptions, and soul-searching dialogues would propel a theological school into leadership that channeled anger into positive steps toward racial reconciliation.

Some student newspapers refused the Horowitz ad, but Duke’s paper, the Chronicle, published it on March 19, 2001. Two days later two African-American students sent out an e-mail inviting a small group of friends to assemble and talk about the Horowitz ad. The invitation brought an astonishing 200 crowding into the Alumni Lounge. The impromptu gathering became a movement. The movement grew and concerns broadened. Offices were occupied. Demands were made. Hundreds of students took part in public demonstrations. The university president responded. Programs were expanded. A task force was established. The divinity school emerged as a powerful resource for the whole community.

In the aftermath, the divinity school emerged from relative obscurity on the university scene to be praised by leaders across the campus for offering “one of the few signs of genuine hope in the midst of the turmoil.” Duke’s president, Nannerl Keohane, and Peter Lange, the provost, complimented it for “vigorous and thoughtful leadership.” Some faculty even suggested that the Martin Luther King celebrations be permanently lodged within the divinity school, an idea Keohane turned aside. She asked the divinity school “to continue to provide the leadership for the planning of the celebration,” but said the event should be understood to be an effort of the entire university.

How did all this come to pass? You might call it divine providence; you might call it serendipity.

As it happened, Jennings and L. Gregory Jones, the divinity school dean, had developed a team-taught seminar on issues of race from both the United States and South Africa. Focus of the project was a university-wide celebration of the life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. that brought together faculty and students from a broad range of disciplines to increase the divinity school’s “developing leadership on the crucial issue of racial reconciliation.” The project was Duke Divinity School’s contribution to a four-year program sponsored by the Association of Theological Schools to explore the public character of theological education.

The events of March 19 and days following transformed the divinity school’s academic enquiry, titled “Geographies of Memory: Theological Reflections on Racial Reconciliation in South Africa and the U.S.A.,” into an instrument of prophetic witness. “We had a much better sense of the issues,” said Jones. “Our ability to respond as well, and as articulately as we did, was informed by our preparation.”

Prior to the Horowitz ad, said Jennings, there had been little public debate at Duke about race relations. “The South African situation allowed us in this country to have a fresh opportunity to examine our situation. We’ve had incredible dexterity in avoiding discussions of race.” That avoidance was amply illustrated in the words of a visiting South African Methodist who, when asked to contrast race relations in the two countries, answered, “In South Africa, we have them. In the United States, you don’t.”

Two immediate results of the “Geographies of Memory” seminar were a request for a response in print from Jones—publication of which was paid for by large numbers of students and faculty—and the emergence of many seminar members as leaders in protests and campus forums. “The Martin Luther King observance had a primary pedagogical purpose,” said Jennings. “What became clear as events unfolded was that there is an incredible need that the university understand and see itself as bearer of public memories—a place where moral memory is preserved.” A subsequent result was the Spring 2002 observance of Martin Luther King with a focus on “The Ties that Bind,” a reference to drawing together of a woven fabric but also noting the constricting and constraining nature of relationships.

“Duke is one of the primary employers of unskilled labor in the Durham area, the vast majority of whom are African Americans and Hispanics,” said Jennings. “Because of our deep commitment to minorities we have become the spokesman for the minority community. African Americans and Hispanics have claimed the divinity school as their own.”

Continuing to build upon last year’s achievements, the divinity school will conduct a “Pilgrimage of Pain and Hope” to South Africa in August “to help provide a deeper perspective for students, faculty and staff.”

Northern Perspective

Without the catalyst of media attention focusing on student unrest, there was less fanfare attending the project undertaken by Phyllis D. Airhardt and Roger C. Hutchinson, two professors at Emmanuel College, Toronto, Ontario. There was, however, no less insight gained and perhaps equal growth in community recognition for the importance of a theological school’s perspective.

|

| Roger C. Hutchinson is professor emeritus of church and society at Emmanuel College, Victoria University, Toronto, Ontario and formerly its principal. |

The issue again had to do with race relations and communications.

As a university-related theological school, Emmanuel College of Victoria University at the University of Toronto has a decided academic presence, but its public character is also shaped by its role as the largest of the United Church of Canada’s nine theological schools.

Their project, “Responsibility, Repentance, and Right Relations: The Churches and the Residential Schools Issue in Canada,” focused on the troubling role of churches in operating boarding schools for aboriginal children in Canada’s northlands and the question of individual and community responsibility. (See “Sorry Past, Shaky Future;” In Trust, Spring 2000.) It involved a one-day event in the autumn of 2001 that featured a prominent aboriginal judge in dialogue with a faculty law school professor. Their public conversation was designed to “highlight the tensions between individual and community rights.”

The conference was rated by the college’s office staff an unqualified success with attendance exceeding all expectations, drawing “publics” from students, faculty, alumni, church executives, clergy, laity “and a few whose questions or attire identified them as non-Christians.”

In addition to initiating discussions and raising consciousness about the residential schools issue, project leaders Airhardt and Hutchinson identified an “awkwardness” between “the language of public discourse and the language of faith” that they had not anticipated.

“There are serious questions about what we take for granted in the audience that’s been invited,” said Hutchinson. “A colleague from law school was surprised by the theological/religious language woven into it.

“There’s a need for self-consciousness of the people invited—carrying forward the idea that public space is public and religious space is private.”

Indeed, noting the absence of theological language in most discussions of aboriginal issues, their report states, “The language of faith tended to be quickly transposed into the language of secular morality. Yet the importance of using the language of faith in dealing with aboriginal issues was obvious, since spirituality was so crucial for those most directly involved.”

|

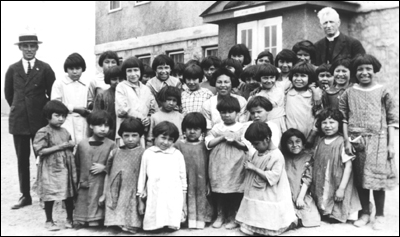

Girls at the residential school at St. John’s, Chapleau, Ontario were photographed in less than Sunday best; because of chronic underfunding schools often found it difficult to clothe children adequately.

Photo courtesy of Church of Canada Archives |

In Hutchinson’s thinking, the Old Testament scripture that gives most insight to their project is the Exodus story of the Canaanites. “Eventually,” he said, “the issue is reframed. The north was not our frontier—it was their homeland. How do we press ourselves back to a prior time? By what right did we come here?”

One of the results of the project, Hutchinson said, was the broadening of the base of understanding within the university of what Emmanuel is doing. Another will be the introduction of a course in law, religion and public discourse taught with faculty from other schools.

Origins of Study

The ATS exploration of the public character of theological education, of which the Duke University Divinity School and Emmanuel College projects formed a part, had its origins in a time that now seems very different from the present. It was funded by a Lilly Endowment grant of $806,510 in 1997.

Then the United States at least was in the midst of the longest economic boom in its history and consumer culture was king. Now the economy is flat, an international war against terrorism has broken out, and world leaders use the phrases of Old Testament prophets to embolden the faint-hearted.

Where once the questions were (1) Why is there no consensus about the public role of theological schools? and (2) What should that role be?, the question now is more likely to be framed by individual schools along the lines of: Which model shall we follow?

Although there is no agreement on an Old Testament scripture in which to root the original enquiry, the most apt may be the Genesis account of the sons of Noah gathering on the plain of Shinar to build the tower of Babel. The tower was to reach into the heavens and bring humans nearer to God, but that prospect inspired God to confuse their language and scatter them abroad upon the face of the earth.

“The purpose,” said former ATS executive director James L. Waits, whom many credit with inspiring the study, “was to raise consciousness of the whole theological community that draws upon religious tradition and prophetic instruction—what it might mean in variant forms.

“The gospel is the unifying counter to the Noah example,” said Waits. “The gospel ought to be the unifying force for our communities.

“If nothing else, the study created a critical analytical awareness,” he said. “That’s an achievement.”

From the effort to find one path came many. From the effort to find one model there rose up many models and a broader understanding of the value of diversity and a rich appreciation for what public character might mean in the wide range of traditions represented in the Association of Theological Schools.

In the words of Robin Lovin, dean of the Perkins School of Theology at Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas who (with co-director Richard Mouw, president of Fuller Theological Seminary, Pasadena, California) shepherded the project over the past four years, the study “developed our sense of traditions and therefore the range of responses appropriate to each tradition.”

“There’s the importance of specificity of responses,” explained Lovin, “and we want to affirm the importance of location and particularity. What you can do in Washington, D.C., is significantly different from what you can do elsewhere.”

“We all think about public character in different ways,” said co-director Mouw. “Theologians at Notre Dame certainly have a strong voice, but it might be different for a Roman Catholic theologian in a small midwestern seminary if a bishop were looking over his shoulder, and it would be very different from a university-based theological school. A university-related divinity school is more likely to address issues on the general campus whereas mainline Protestant denominational schools are more likely reflecting on issues of their denomination; and evangelical Protestants really have a problem with being connected to a strong political presence very little influenced by theology.”

Mouw described the first four position papers (which were completed in 2000) as excellent statements exploring and sorting out the contours of theological education. “The goal we had,” he explained, “was to get people in theological education to ask what is the obligation in theological schools, in any given context, addressing issues of public life.”

The subsequent eight projects delighted him with their quality, creativity, innovation and impact. Mouw said that reflecting on the findings made him much more aware of the overall questions.

“It forced me to take an inventory which I’d never done before,” he said. “We have courses in social ethics [at Fuller] but haven’t done a very effective job. I look at our curriculum and ask: Any items missing? I think there are. We need to provide resources for homelessness, hunger, inter-religious tensions.”

The initial study and ensuing projects “reaffirmed the insight we started with that theological schools are not as visible as they think they are,” said Lovin. “Most of us think we are prominent in our own communities and there’s a lot of evidence that that’s just not true. There’s a strong sense that it’s important to do something about that.

“It’s the same thing with media attention,” he said. “We are bemoaning the fact that we don’t get enough calls but the message from the media is that ‘We’re all the time looking for this kind of information and we need it on short deadlines.’

“What are we not doing? What do we need to do?” he mused. “It’s a matter of demonstrating usefulness. … There’s a good sermon hidden in there somewhere,” he said. “It’s not really about you.”

The initial study of the public character of theological education was undertaken in 1998 “to understand the ways in which ATS members schools made their presence known in the churches, in their local communities, and among the wider public.”