As these examples show, structuring a relationship between a university and a theological school, while dauntingly complex, can hold undeniable benefit for those who opt—or find themselves forced—into it. What are the economies and other advantages? What are the costs—fiscal, human, and religious? What are your institution’s strategic opportunities for collaboration?

It was obvious that they were serious. It wasn’t a scare tactic,” said Charlotte Cochran, former board chair of Atlantic School of Theology. She was talking about a spring 2000 meeting at which Jane Purves, Nova Scotia’s deputy minister of education, announced that the provincial government expected to cancel the school’s annual $750,000 (Canadian) grant, almost a third of the school’s operating budget, in nine months.

|

William Close and Charlotte Cochran, in front of their board room window that overlooks the Northwest Arm of Halifax Harbour.

Photograph by Sandor Fizli

|

The announcement was not a complete surprise. It had been “looming on the horizon,” Cochran said. Halifax (population 360,000), Nova Scotia’s capital, has six institutions of higher education. There are five others elsewhere in the small maritime province. That’s one fewer school than a few years back, when the provincial government pulled the plug on a technical school and forced it into a less-than-entirely-happy merger.

William Close, AST’s president, had discerned the signs of the times, and was able to hear out the minister and reply—as he paraphrases it—“Yes, you can drop the ax on us and you can get away with it. But that’ll be bloody—and we’re already in conversation with another school.”

Fightings and Fears

The story has a happy ending. AST has affiliated with Saint Mary’s University, located a few blocks up the hill. In retrospect Cochran can wholeheartedly say, “We have a lot for which to thank the government.” She explains that it was time for the school to look inward, and that it probably wouldn’t have done it without being forced.

Forced it was, however, and the situation did not allow for calm introspection at the time. “I didn’t eat a lot before some board meetings that year,” said Cochran. Some members of the community had to be convinced that the government was serious. Others immediately went into full offensive mode, determined to fight for the school. Cochran and Close considered the flood of public support needed to win such a fight unlikely to pour in, pointing out that most Nova Scotians had never heard of the Atlantic School of Theology.

And then there was the matter of welding together a board of complex and diverse origins. AST was founded in 1971 as a successor to three schools: the divinity faculty of the University of King’s College (Anglican), Holy Heart Theological Institute (Roman Catholic), and Pine Hill Divinity Hall (United Church of Canada). The AST board comprises five members from each founding denomination, plus two students, two faculty members, and the president. “We broke up into small groups,” said Cochran, “and worked very hard at mixing up the groups. It worked so well that now we can’t have a discussion without small groups, and if you didn’t know the denominations of the members, you might not guess.”

Add to the mix the still existing board of the late Pine Hill Divinity Hall, which owns the property on which AST is located. A spectacular site it is, pine-studded, sloping down to the Northwest Arm of Halifax Harbour, fronting on a street in a pricey neighborhood with some of the only buildings to survive the 1917 explosion that leveled most of the city.

Cochran remained hopeful through these fightings and fears. “AST was founded on trust and cooperation,” she said. “It happened once. Why couldn’t it happen again?”

Perils and Promise

Why not indeed? Even the most organic sorts of arrangements between theological schools and universities are fraught with unexpected perils, but smooth working relationships still can emerge. Witness the reintegration of Talbot School of Theology of La Mirada, California, into its parent school. The Bible Institute of Los Angeles was founded as a training center for lay ministers in the early 1900s. By 1952, it spun off Talbot Theological Seminary. Thirty years later, when the school acquired a graduate school of psychology, it restyled itself Biola University, and Talbot returned to its parent as “Talbot School of Theology of Biola University.” Interestingly enough, according to Biola’s longtime president Clyde Cook, it wasn’t the affiliation of the school but its name that posed a problem. “The perception of some people was that theology schools connected to universities carried a liberal stigma,” he said.

|

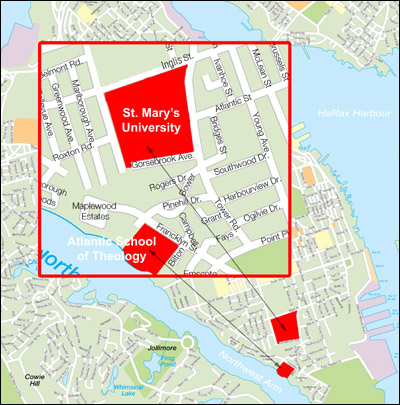

Atlantic Theological Seminary is now affiliated with Saint Mary's University, located only a few blocks away.

Map by Robert Lunsford

View a larger version of the map.

|

That issue is long since resolved, and Talbot plays a far more central role in Biola’s life than Atlantic is likely ever to play in Saint Mary’s. There is a wide array of ways to be a university-related school. At Biola, each school provides instruction in its area of expertise for the whole university. That means, among other things, that Talbot coordinates the thirty-unit core of Bible and theology required of undergraduates. The extra faculty required in turn makes for a larger pool of faculty to teach at Talbot.

A Set of Choices

The AST board first heard of the impending disaster in June 2000. By September, Close and Cochran visited the minister to float the idea of an affiliation with Saint Mary’s built around a center for ethics. A flicker of her eyelash convinced them they might be on the right path. Purves requested a specific proposal.

It wasn’t quite so easy as that.

The community was informed in detail of the situation in November, and Close began a phase of focus on the pastoral nature of the presidency. That same month leaders of the school’s founding parties met and agreed to do everything possible to help the school survive. Another meeting in December brought an assurance from the minister that a solution that did not involve leaving the present campus would be entertained if capital and operational vulnerabilities were addressed.

On December 11, faculty, staff, and students were invited to a discussion with board members before their regular meeting. At that meeting, the board hired a consulting firm, KPMG, to help the school consider its options. Among the possibilities were:

-

Merger with another university or theological school.

-

Continued autonomy with contractual collaboration with a university.

The province began 2001 by committing up to 50 percent funding. As the year progressed, the school successfully asked for—and received—an additional $144,000 for consulting and legal fees.

By February, the consultant presented a plan that called for:

-

Attending to deferred maintenance.

-

Pine Hill’s agreement to transfer property ownership to AST or to contribute a substantial amount to develop a new facility on a university campus.

-

A decision to affiliate with either Dalhousie University or Saint Mary’s University.

Saint Mary’s is just a few blocks uphill from AST, Dalhousie less than a mile away. Both are old schools, now secular but grown from religious roots, Saint Mary’s once Roman Catholic, Dalhousie of UCC origin. They presented different strengths and weaknesses. How does one consider the comparative relevance of a medical school (Dalhousie) and a business school (Saint Mary’s) to a theological school? Part of the decision came down to space. Dalhousie offered some dilapidated buildings in the middle of its rabbit warren of a campus that could be torn down to make room for a new building. Saint Mary’s was more interested in AST staying where it was and possibly reconfiguring AST’s mothballed 1898 Building as a center for ethics and public affairs.

Saint Mary’s already had a connection to AST in the person of its president, Colin Dodds. While he was vice president of Saint Mary’s, he rented for several years the house that Close now lives in. Close’s installation service was held in the Roman Catholic church on Saint Mary’s campus, which is larger than AST’s chapel. The two presidents share a strong sense of the public role and the public obligation of institutions of higher education, the connection between public funding and public good.

Centering

From this common view emerged the idea of an ethics center, a place to think across disciplinary and cultural lines about what Dodds calls “best practices.” Saint Mary’s has wide international connections, drawing students from more than 100 countries and conducting programs in various parts of the globe.

Once again, the presidents’ timing was impeccable. Just as the plans for the center were proposed, the corporate world was rocked with a series of scandals, and the need for the teaching of ethics was apparent to all, including potential funders.

Here, too, is a way for the schools to work together with each school making a major contribution.

Little Gems

The search for places where small frogs can contribute to a big pond is a familiar one for Arthur Holder, dean and vice president for academic affairs at the Graduate Theological Union. Most of the GTU’s nine schools cluster around the campus of the University of California at Berkeley. Six perch on a hill just one block north, another is just across campus. The GTU and Berkeley are separate entities, but they have cooperated to the point of sharing Ph.D. programs in Near Eastern Religion and Jewish Studies (the GTU offers its own Ph.D. in eleven other areas). The schools cooperate in the operation of four centers—ethics and social policy, religion and culture, women and religion, and Jewish studies.

It is possible to cross-register, although the differing calendars of the GTU and the university make it difficult. Some history and literature majors take courses at the GTU, but the traffic is mostly in the other direction. From time to time courses are offered jointly (a current one is titled “Ecology/Gender/Religion/Ethics”), and some GTU faculty are listed in the university catalogue. Holder’s assessment of the relationship between the schools is: “We’re very small. Most people (at the university) aren’t aware of us. The people who are, are very supportive.”

Betrothal

In June 2001, Close and Dodds signed a memorandum of understanding that committed AST to enter into an affiliation with the university. It is not a merger. “Nothing shall be interpreted as derogating in any way the independent status of either school,” the document proclaims. The details of that affiliation will be worked out gradually. AST is still figuring out, for example, where cooperation will save them money.

AST dean David MacLachlan is spending much of his time thinking about how the schools can use each other’s faculties. “We think of them as big, of course, but in the area of religious studies, we’re bigger!” Beyond the obvious areas of connection, there have already been joint courses—one on theology in film, another on religious diversity in Canada. There is a process of discovery at work here, and it will take time to find the obvious connections, the places where the schools can enrich one another.

Jazz on Hold

The first hint that Perkins School of Theology is part of Southern Methodist University might elude the casual telephone caller, who might wonder why when put on hold, one is treated to the big band strains of “Pennsylvania 6-5000.” William Lawrence, Perkins’s dean, is happy to explain. “That’s the SMU jazz band, sometimes known as ‘the best dressed band in the land.’” Already, before saying it, he’s making his point about the particular gift of the university-related theology school. It isn’t long before he makes it explicit, “A university is the best place for theological education because a university most closely resembles the real world in which graduates will engage in ministry. The people engaged in all manner of work at the university are the very people one finds in the pews.”

Perkins is one of six graduate schools of SMU. All are fully a part of the university, which means, among other things, they don’t do their own hiring or determine tenure. Each school has an “executive board,” but the boards serve in a purely advisory capacity.

Perkins shares a dilemma in fund-raising with some other theology schools that are part of a university. While they raise much of their own money, they are also part of the university’s development office, and the director of donor relations allocates the donors, some of whom give to specific schools but some of whom are only asked for gifts to the university. And as Lawrence points out, “Our graduates are not usually in the best position to make large contributions. They can serve as doorways to those who can.”

Toward Tomorrow

AST’s financial challenges have not disappeared, but they have eased. In July 2001, the province began funding AST, through Saint Mary’s, at about 90 per cent of what it had been contributing in previous years. That November the Pine Hill Divinity Hall board agreed to sign over much of its land and most of its buildings to the AST. It will sell the remainder, some of which the AST hopes to buy.

So—having survived, AST is now faced with its biggest fund-raising enterprise ever; Close estimates that the campaign will seek at least $3 million.

Close’s first term was up in the middle of the most uncertain time in the process. The AST board waited a year to renew it, and then voted unanimously to do so.

The board has changed as it weathered the crisis from what Close describes as a maintenance board to a strategic one.

Cochran has cycled off the board, but is still very much a part of the life of the school. When Close was on sabbatical last year, she occupied his office in order to continue the conversation with Saint Mary’s. Her comment now on the experience of crisis? “I really did see it as an opportunity, and I had a lot of faith—faith in our leadership and faith that we’re necessary to our churches and community.” Such a faith allows for change, for collaboration—and for hope.

Union Hails Columbia

Union Theological Seminary in New York has formalized an agreement with Columbia University as part of a strategic plan aimed at putting Union on solid financial ground and reforming its academic programs (see “A Matter of Degree,” In Trust, New Year 2003).

An agreement signed in March leased two of Union’s buildings to Columbia for forty-nine years, and transferred ownership of the collections of the Burke Library (which will remain on the Union campus). These measures are expected to save Union $3 million a year. The practical cooperation already existing between the schools is evidenced by the e-mail addresses at Union, which end “@uts.columbia.edu.”

Academic connections between the schools will be enhanced as Columbia’s religion department relocates to Union’s campus (the Center for the Study of Science and Religion has been there since last autumn). Two of Union’s church history professors have been granted full faculty status at Columbia. There are plans to add more joint doctoral programs to those already existing in the religion and social work departments; cross-registration between the schools will also be made easier and cheaper.

Union’s renewal, though, will have a substantial price tag. The school has announced a $39 million “comprehensive campaign.” By the beginning of April, half that goal had been given or pledged. “Union’s board members committed to $7.75 million,” said Joseph Hough, Union’s president.

Kevin Mannoia, the dean of Haggard School of Theology of Azusa Pacific University in Azusa, California, in his “Perspective” department article “School and Church at the Center” looks at the development of study centers as a way to draw evangelical theological schools and churches closer together.

Read a comment on this article: “Ongoing Connections”