|

Glenn T. Miller is academic dean of Bangor Theological Seminary in Bangor and Portland, Maine.

(PHOTO BY GLEN SCHNEIDER) |

I. Freedom and control

In the 19th century, American education developed in harmony with the nation's vibrant localism and its passion for freedom. A handful of devoted men and women would see a need, spot an opportunity, or desire to develop some land. With the aid of willing state legislatures and denominations hungry for prestige, those educational entrepreneurs would establish an academy, a college, a law school, or a theological seminary. Catholic religious orders often functioned much as Protestant denominations did — enlisting support, securing approval from the state, and creating schools after their own likenesses. In this hearty atmosphere, schools could experiment with curriculum, admissions, and governance. All that was needed: grit, determination, a little capital, and a willing board of trustees.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the nation had grown economically and culturally. Giant corporations and new forms of communication and transportation weaved the localism of the past into a new national identity. If the passion of the 19th century was freedom, the passion of the new century was organization, energy, and — above all — control.

As Americans tried to tame the new leviathan that they had created, they most often turned to state and federal governments for muscle and direction. In retrospect, it seems that Americans moved rapidly from the progressive legislation of the new century to the wartime regulations of Wilson to the Depression-inspired New Deal. Only government seemed big enough, large enough, and strong enough to address the problems of the times.

II. Self-regulation

In large measure, American higher education escaped the governmental regulatory net. Nevertheless, colleges and universities were unsure of the value of one another's credits, and standard bachelor's degree programs ranged from highly sophisticated encounters with the best and truest of what was known, on the one hand, to little more than a four-year romp through late adolescence, on the other.

|

|

|

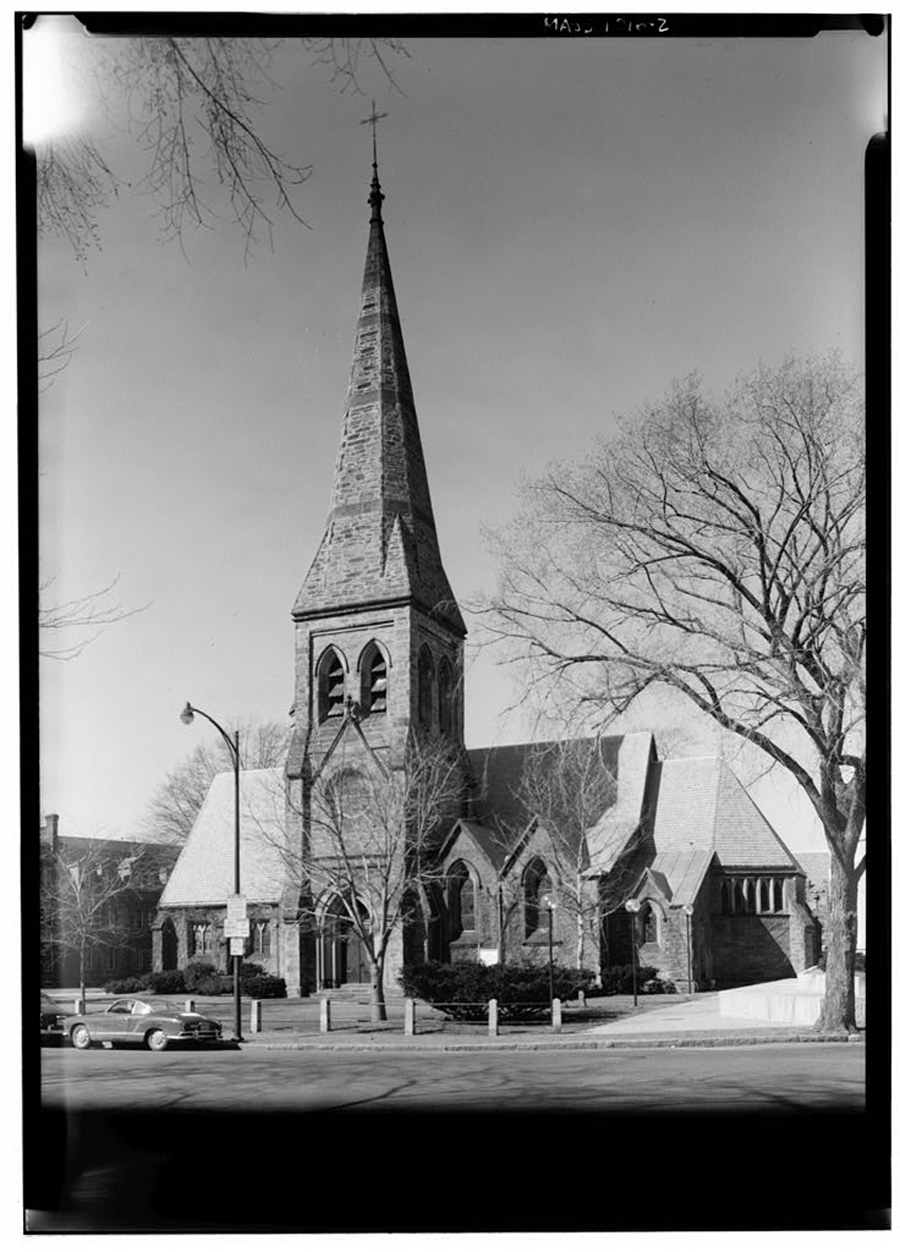

The Episcopal Theological School was founded in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1867 and merged with the Philadelphia Divinity School in 1974 to become the Episcopal Divinity School. This photo of the school's St. John's Memorial Chapel was taken in 1967. (PHOTO BY GEORGE M. CUSHING FOR THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

|

Professional education was in little better shape. Although the marketplace disciplined the professional schools somewhat, they also struggled with the fundamental issue of ensuring the quality of their programs and their graduates. To solve these problems, schools banded together to form associations that established standards for membership. The members of these associations agreed to accept the credits of other schools in the association, and, in turn, to work toward mutual improvement. Of course, associations did not level the educational playing field, but they did establish important minimums that schools (and, later, the public and the government) could trust. Requirements for positions came to refer to graduates of an accredited college or university.

Seminaries came comparatively late to the accreditation movement. In part, this was because the real test of a theological school was its ability to serve the churches that directly and indirectly paid its expenses. Further, within each denominational family, various seminaries formed networks that informally handled such issues of institutional cooperation as transfer of credits and recognition of degrees. The network of church colleges also provided a system of recognition and transfer. For Catholics, ecclesiastical recognition made the questions of transfer credits and degree recognition moot. Also, general educational strength made accreditation less important until after Vatican II.

III. Problems

Among Protestants, however, problems with seminaries began to develop in the 1890s and grew more acute during World War I and its aftermath. Perhaps the most serious problem was theological. As heirs of the Reformation, most Protestant churches inherited an understanding that theology was a university discipline to be conducted according to the canons of intellectual life. Whatever might be true of the organization of the schools, the intellectual infrastructure of seminary life was the larger university world. But where did seminaries fit into this larger ecology? The largely accidental fact that seminary training, at least in the culturally influential Presbyterian and Congregational churches, took place after college suggested that the schools were graduate professional schools, similar to other such schools.

The transformation was hastened by the erosion of the traditional understanding of the pastor as the advocate of his denomination's theology. Instead, ministers came to see themselves as experts in religion who had special insight into human psychology, sociology, and education. The voice from the pulpit no longer spoke in the harsh terms of an almighty judge but in the more moderate speech of a personal friend who wished the believer a good life and a blessed eternity. The new style of ministry required (or so its advocates believed) a style of seminary that could integrate experience around its religious core.

IV. Chaplaincy

The First World War changed many things — among them, the role of the chaplain. Traditionally, regiments had chosen their own chaplains, or some influential politician had suggested a "fighting parson." But the leaders of this war, despite their rhetoric about American traditions and American values, were committed to a conscript army, professionally led and scientifically managed. They needed chaplains who could serve men of many institutionalized faiths — and of none. Formal seminary training was one way to measure such expertise, and the military inched its way towards requiring such certification.

The end of the Great War encouraged seminary leaders to take a close look at cooperation among each other around academic standards. Drawing on the theological acumen of theologian William Adams Brown, schools were able to use the work of the ministry as the primary hallmark of a new set of standards for theological schools. Not only did this sidestep (or perhaps leap over) such serious disagreements as whether to require studies in Hebrew and Greek, but it provided a yardstick for collecting information and evaluating institutions. When combined with some standards from colleges and universities (such as the need for adequate libraries and financial resources), the seminaries had a working set of standards that they could use to control their institutional life. These standards were established just in time to be useful in recruiting and certifying the chaplains who served in the Second World War. Some Canadian seminaries joined their U.S. counterparts in seeking accreditation at this early stage, and many others later sought accreditation.

V. The silent revolution

Accreditation proved to be the agent of a silent revolution. The combination of a set of attainable standards with a 10-year report and visit meant that schools could concentrate on long-range improvement. In time, more schools had instructors with advanced degrees, more libraries had the most important contemporary books, and more curricula included counseling or psychology. None of this was dramatic — no one can provide a date when the change took place, and no one can name one leader whose career was capped by its completion. But slow, steady change re-created American theological education. Not surprisingly, graduation from an accredited seminary became the sine qua non for Protestant military chaplains and for ordination in the mainstream Protestant denominations.

During the 1930s and early 1940s, liberal theological educators more or less dominated theological education, with only a handful of schools standing outside the liberal neo-orthodox consensus. Strident polemics and such public events as the Scopes trial appeared to leave evangelicalism on North America's cultural margins. After World War II, however, the new evangelicals reclaimed the conservative heritage and established a number of important institutions, including Fuller Theological Seminary.

In more recent times, accreditation has continued to have its significant, but often hidden impact. The Association of Theological Schools was an important midwife, enabling evangelical theological schools and evangelical theologians to reenter the national scene. Once evangelical schools had crossed the bar of accreditation, their teachers, students, and graduates had new prestige in American life. The association also had a behind-the-scenes influence in increasing the number of women and minorities in theological schools, and in affirming the place of historically African-American institutions.

As the dean of a small theological school, I admit that I dread the 10-year ritual of self-study and visiting team. The workload on a small faculty and a small staff goes up exponentially. And as the steering committee searches for one more "evaluative loop" or "assessment tool," the temptation to cry "enough already" is ever present. Yet, when one reflects on the effects of the process on one's own school, not to mention on all of theological education, one realizes that this has been one of the most potent shapers of American theological education.

|

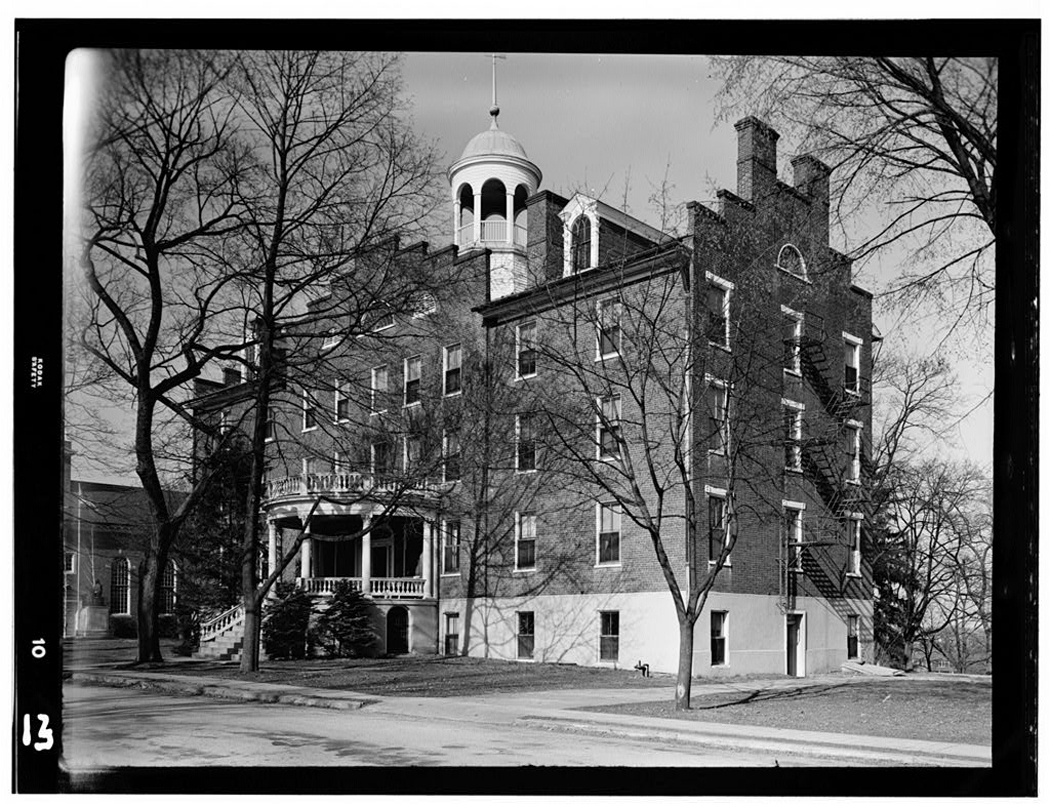

| The Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg was founded in 1826 and moved to its present location in 1832. This photo of the Main Building was taken in 1950. (PHOTO BY FREDERICK TILBERG) |