Editor’s note: In this edited excerpt, the authors of (Not) Being There highlight several challenges that seminaries face and offer a glimpse at the “what’s next” for online distance education.

Theological schools, rarely at the forefront of technology, are facing the promises and challenges of moving into the digital age. Their reasons for expanding into online education are obvious: their desire to attract new students and retain current students; their need to strengthen their financial bottom lines; and their determination to prepare a new generation for ministry regardless of time and location restraints.

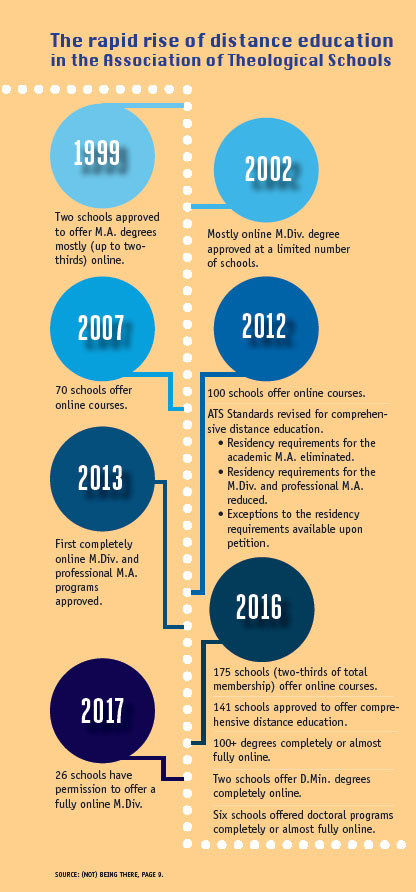

Statistics are encouraging. Although enrollment in schools accredited by the Association of Theological Schools (ATS) declined by 11 percent in the past decade, online enrollment grew by 195 percent. Tom Tanner, ATS director of institutional evaluation and accreditation, notes, “In the past five years, less than a third of schools without online students grew, while almost half of the schools with at least 100 online students saw enrollment growth.” If these trends continue, says Tanner, “a majority of ATS students may be enrolled online within a few years; one-third already are.”

Clearly, online education is here to stay. Also clear: There are still obstacles to overcome.

For schools that ventured early into online education, it’s often been a steep — and expensive — learning curve. They’ve had to keep pace with ever-evolving technology. Learning management systems have been purchased and discarded because they failed to meet the needs of students or faculty. Then there’s the challenge of helping faculty make the transition from onsite to online instruction without forfeiting quality. Some 60 percent of the deans who responded to an ATS survey indicated that training faculty to teach online was one of their top concerns. Twenty percent of the deans mentioned that “getting faculty acceptance” also was an issue at their institution. Reasons that faculty gave for their reluctance included:

-

Practical. “I don’t know how to do it.”

-

Pedagogical. “How can I teach something to students who are not sitting in my classroom?”

-

Personal. “I don’t have time.”

-

Institutional. “We don’t have the resources.”

-

Communal or relational. “How can we form community if students aren’t on campus?”

Online education takes (a lot of) time

As one professor commented, “To employ technology in the classroom with success, instructors must make a significant commitment to the effort. This requires two things: pedagogical reassessment and the willingness to invest the time and effort necessary to design and produce quality learning experiences for the students.”

Help is available. Responding to the need for professional development, several organizations — the Wabash Center for Teaching and Learning among them — offer a range of training opportunities. However, only 20 percent of the deans in an Auburn survey say they require faculty to take training in teaching online, and another 49 percent say they only encourage faculty training. The report also indicates that less than a quarter of faculty members who teach online have received formal instruction in doing so.

Help is available. Responding to the need for professional development, several organizations — the Wabash Center for Teaching and Learning among them — offer a range of training opportunities. However, only 20 percent of the deans in an Auburn survey say they require faculty to take training in teaching online, and another 49 percent say they only encourage faculty training. The report also indicates that less than a quarter of faculty members who teach online have received formal instruction in doing so.

Creating a new online course is more time consuming than creating a face-to-face class, according to nine out of 10 faculty members enrolled in the Wabash workshop on teaching online. Three out of four said the amount of time it took to teach and assess online students was “more” or “far more” than the time to teach and assess students in a traditional setting. A few professors disagreed with this assessment, explaining that once a new class is “bug free,” it often requires less time. Some schools give a stipend to professors developing new online courses; some lighten the instructors’ teaching load.

Another time-related factor involves the informal give-and-take conversation, often at the end of a class, when a teacher answers random questions. In a classroom setting, the professor can address all the students at one time. By contrast, online teaching may require the professor to answer the same question repeatedly because interaction is of the one-on-one variety. This caused one professor to estimate that a residential classroom of 25 students is “probably equivalent to teaching 18 students online.” The unintended fallout from this is that an instructor may have less time to devote to other academic responsibilities. As one professor explained: “It’s cut down on research and writing and connecting with colleagues at other theological colleges.”

Building relationships and community

Administration and faculty are often concerned with how to make online students part of a school’s community. More than a third of respondents to the ATS deans’ survey cited “building relationships” as a challenge for their institutions. Others offered rebuttals and said they felt they knew some of their online students better than those sitting in their classrooms. Some commented that at many schools, the majority of students do not live on campus anyway; they commute and arrive just before class begins and leave immediately afterward to get to work or to other commitments. Stephen Graham, senior director of programs and services at ATS, verifies this. He wrote in a blog post that just over a quarter of today’s students either live on or adjacent to campus, while 47 percent are local commuters.

Closely related to the concern about preserving community is the question of student formation. More than half of the deans in the ATS deans’ survey indicated that doing formation online could be difficult. They wondered: How do you ensure that your graduates are spiritually, psychologically, and socially healthy and able to handle the responsibilities entrusted to them as leaders of a congregation or parish? Some faculty who are committed to online teaching challenged the premise of this question because it assumes faculty can accurately assess their residential students’ preparedness for ministry.

In fact, a growing number of educators believe that training for ministry is more — not less — effective if students remain in their own context rather than be uprooted and moved to a residential campus. Their reasoning: The integration between classes and the “real world” is likely to happen more quickly and more organically if students are living, learning, and perhaps working, in their own faith environment. One dean commented on the ATS deans’ survey, “Because students in the online program learn in the ministry setting in which they will serve, we have had virtually no problems with graduates failing in their first congregation.”

Definitive proof may be in the numbers. The ATS Graduating Student Questionnaire (GSQ), administered at 183 schools to more than 6,200 graduates, enables researchers to compare learning and growth outcomes for students who did most of their degree online with graduates who did the majority of their degree on campus. Results from the 2015–16 GSQ are surprising. In the personal growth areas of “Strength of spiritual life,” “Trust in God,” and “Ability to live one’s faith in daily life,” online graduates rated themselves much higher than the onsite graduates.

Findings and outcomes

At this point, evidence indicates that online education produces outcomes at least equal to the level of traditional classroom outcomes. Some would go so far as to say that their online students do better overall in a course than those in a traditional class. Faculty members — even those with some hesitancy about online teaching — acknowledge that in online courses, there is “no lurking in the corners” (i.e., students can’t hide from class discussion — the structure requires that every person contribute). In an actual classroom, students can riff off of students who are eager to talk and thus hide the fact that they have not yet done the reading. Students who are introverts often participate more in online discussions than they might in a more traditional classroom. They have time and space to think and are not always competing with more talkative students.

Clearly, this report shows we are past the point when the efficacy of online education can be questioned. “Our recent past, and our present results, indicate online learning is becoming a proven pedagogy for theological schools,” says Tom Tanner, summarizing the finding of the survey of ATS deans. “This educational model is proving to be effective, not just for many, but for most of our member schools.”

Seminarians seem to agree. On the 2015–16 GSQ, students who took most of their classes online scored their skill level much higher than those who took the majority of their classes on campus in such key areas as “Ability to give spiritual direction,” “Ability to administer a parish,” “Ability to teach,” and “Ability to lead others.”

So, should a seminary or theological school move in the direction of online education? It’s a good question to ask, and only the school’s governing board, administration, and faculty, listening to the school’s constituency, are in the positions to respond. The market is indeed becoming saturated, and schools with limited resources wonder how they can compete against well-established online programs. Market research will be required to see if an institution has a particular niche to fill, a specific program to offer that is not available online elsewhere, or a population it can attract because of its religious tradition, denomination, or ethos.

The report at a glance

The report at a glance

The 49-page Auburn Studies report, (Not) Being There, tracks the enthusiastic — although belated — move by many North American seminaries to embrace online distance education. The comprehensive report includes statistics, depicted in easy-to-digest graphics, that verify the growth of online education in the decade leading up to 2018. Case studies illustrate how three schools chose to take the plunge into digital delivery, and why one seminary has thus far moved only hesitantly. (See “Cautious entry” below.) In addition to giving readers an honest assessment of the challenges and benefits of online education, the report offers a primer on how to jumpstart the process of implementing online education.

Three key findings emerge from the authors’ research:

-

Online education is pushing the boundaries of who attends theological schools.

-

Online student outcomes equal or exceed those of on-campus student outcomes.

-

The old divide between traditional, online, and hybrid courses is disappearing.

To access the full report, visit auburnseminary.org/report/not-being-there.

How to jump-start an online program

Schools contemplating a move toward online education can benefit from the experiences — good and bad — of the early adopters. Based on our interviews with veteran faculty and consultants, we offer these guidelines:

-

Take seriously the concerns and fears of stakeholders by highlighting how other schools have addressed these issues.

-

Ensure that the administration is fully committed to online teaching and communicate that commitment to faculty.

-

Ease into the digital age by encouraging faculty to go paperless, post materials for their classes online, set up online discussion forums, or use video conferencing for students unable to attend a lecture.

-

Start small by offering a sampling of online courses taught by faculty who are on board. Their success and testimony will win over more reluctant faculty.

-

Get the buy-in of key senior faculty who have more influence and hold greater respect among their colleagues.

-

Make training available in-house, through an outside resource, or by assigning mentors.

-

Encourage faculty to team-teach an online course, matching digital veterans with colleagues who are less secure in their technological skills.

-

Consider offering a bonus or easing the teaching load for faculty designing and teaching an online course for the first time.

Just as seasoned faculty members are constantly tweaking classroom courses that they have taught for years, so are online instructors always on the lookout for improvements in content and in the delivery of that content. To promote camaraderie, one professor told us that he asks students who are separated by hundreds of miles to collaborate on practical projects. “The delivery becomes as important as the product,” he said.

Another professor has introduced a way to cut expenses for students and at the same time, build community. Rather than requiring students to buy several expensive textbooks, he forms teams of students and suggests each person purchase a different book to review or summarize and discuss the findings with the group. “You learn a lot by explaining to others what you’ve learned,” he says. “This not only decreases costs for students, it also results in better learning as the student becomes the teacher or facilitator in discussions.”

Cautious entry

Columbia Theological Seminary has been hesitant to join the wave of schools embracing online education. A few faculty members are champions of online teaching, but other faculty members are doubtful as to its efficacy and wary of its expense.

Community life is a major part of the ethos of the Decatur, Georgia, institution, with chapel conducted four times a week, communion offered on Fridays, and on-campus housing provided for seminarians and faculty members. To some, offering online courses feels like a distraction from that shared life.

Before launching any initiative, the faculty wants to know what the costs will be in terms of technology, teaching loads, and time commitments. “Better caution today than regret tomorrow” is the general feeling. Specific questions they have regarding a move to online education include: Do we have the necessary infrastructure in place? What kind of training will be available for digital newcomers? Have faculty and staff fully bought into the online education concept?

Ironically, looking for these answers inspires a final pragmatic question for the administration to tackle: Is it too late to enter what appears to be a saturated market? Dozens of theological schools in North America are offering entire graduate degree programs online. Many of these schools have been tweaking their digital delivery process for 10 or even 20 years. How can a school such as Columbia, with limited experience, hope to compete against these pioneers? In short, they ask, should we even try? They consider that perhaps a wiser path forward is to build their brand as a beautiful residential seminary where students and faculty live, learn, and worship in community with each other.