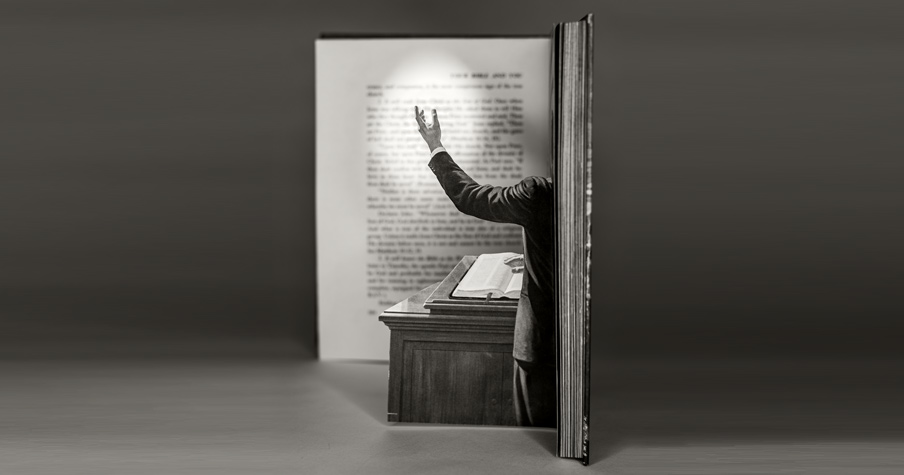

Photo illustrations by Thomas Allen

A multiyear project is opening fresh conversations about the current moment and the future of theological education.

With an array of leading thinkers from around the world weighing in, the Theological Education Between the Times project is creating fertile ground to explore critical issues in the field. The project, based at Candler School of Theology at Emory University and funded by Lilly Endowment Inc., will produce 12 books that provide fresh views of current themes. In Trust magazine is pleased to expand the conversation started in the project by publishing essays by each of the authors. That began with three essays in the Autumn 2020 issue and continues here with Harvard Divinity School scholar Dr. Mark D. Jordan. His book “Transforming Fire: Imaging Christian Teaching” was published this year as part of the series.

You may remember a passage from C. S. Lewis’s The Last Battle, the one that tells of a stable with an “inside bigger than its outside.” The immediate allusion is to Bethlehem, but the image has wide application in Christian teaching. For example, seminaries must be larger inside than out, since Christian scenes of instruction expand unpredictably for those who enter them with hope.

“Scenes of instruction” is my shorthand for the imagined spaces opened by persuasive teaching. The spaces are passionately shared and intensely individual. They are bodily but invisible. Watching a recorded class, you can follow the words and gestures that help elicit a scene of instruction, but most of the scene happens in the heads and hearts of the participants. The building, the room, the board or screen, even the teacher’s performance – these are instruments for an event that expands beyond them. Especially in Christian teaching, neither the causes nor the effects can be controlled by us. Like a profession of faith, learning Christian theology relies on divine gift. When I was starting out as a teacher, I used to console myself that the classroom always held a better teacher than myself – namely, the book I was trying to share with my students. My more ardent wish – which I could never trust as an expectation – was that a third Teacher would join us.

The paragraph you’ve just read doesn’t proclaim novelties. Imitating Lewis, I offer in it only another version of some of the oldest Christian counsels. It can be important to say old things again, especially in times of institutional crisis. We may profess the counsels, but we don’t often turn to them for practical help. We should, especially when their implications disrupt our favorite assumptions.

The inside is bigger than the outside because it seeks to welcome the spoken creation.

If you ask, “Where is Christian teaching done?,” the best short answer is probably, “In scenes of instruction.” It may also be true to say, “Christian teaching happens at schools,” but that second answer is likely to mislead. It confuses means with ends or tools with art, as if a symphony orchestra would squander all its money on a Stradivarius, leaving none to hire a violinist. For a long time, the educational version of such a confusion has emphasized that seminaries ought to become more like other professional schools. Once you leave aside whatever distinguishes them, what would such schools have in common? Efficient governance, a teaching staff shaped by the reigning guilds, up-to-date buildings, a state-of-the-art library, a convincing admissions office, HR managers, outcome measures, risk assessments. But Christian scenes of instruction require none of those things. Christian teaching has come to life in a huge range of institutions, because an institution, as much as a building or a guild or a business model, is fundamentally different from a theological scene. The physical and institutional emplacement of theological scenes is both secondary and historically variable. After all, our Teacher was born in a stable.

Let me be clear: To say secondary and variable is not to say negligible. The scenes recorded in our scriptures and traditions took time for enacting or composing, then more time for interpreting, meditating, commenting. The leisure needed for teaching or learning can be expensive. Many practical skills are required to run anything like a sustainable school. Still, the form of a theological school cannot be deduced from the scenes taught within it. A scene of instruction does not dictate plans for governance or fund-raising. It will not even yield a detailed curriculum with fixed outcomes. Any number of institutional forms have served admirably over centuries to shelter theological scenes. (If you are tempted to ignore those centuries, ask yourself just how confident you are that we teach Christian theology better now.) The decisive thing for theological education is not a specific institutional structure.

If I were to emphasize any connection between scenes and institutions, it would be a vulnerability. Institutional vices or distortions can make it harder to activate scenes of instruction. So many things can go wrong. For example, a school that wants to house theological scenes must integrate ethical habituation with freshness in worship. It must help theology to have independent relations with adjacent arts and sciences. It must encourage robust exercises of imagination and the many genres of writing that flow from them. (If I could dictate curricula to seminaries, I would require every student to take a course in creative writing. Remember that our gospels are narrative told four ways.) An institution for teaching theology must welcome strong pedagogies while cultivating resistance to abuse. What is most important and most difficult is that it must not circumscribe the effects of what it teaches. It cannot succeed in controlling grace, but it can kill off theology by trying to do so.

I have not forgotten that times are hard for many schools of theology in the United States – and harder now than before the pandemic. There are many motives for anxiety. Still, we cannot afford to cling to established forms. We need instead as many experimental structures for sheltering theology as we can imagine – with and without accreditation or (forgive me) denominational certification. We need just as urgently improvisations of writing. The page remains a powerful space for trying out new scenes. If the future of theological education in the United States looks to be poorer and smaller than what it has been, we might relearn from already marginalized communities the riches of the Word.

When we find it hard to gather hope, when the daily task of teaching and learning feel empty or overwhelming, perhaps we can remember how much is at stake. Struggles over seminaries have regularly had large effect, even though they have never constituted more than a small fraction of national systems for higher learning. I like to think that this is because theology depends on the well-being of every other way of knowing – and shows its dependence by grateful learning. When theologians proclaim that God entrusted revelation to human words, they declare their stake in the flourishing of any learning through words. They also give voice to a conviction that any uttered truth points towards divinity. The inside is bigger than the outside because it seeks to welcome the spoken creation. Is that hope enough?

Dr. Jordan's new book, Transforming Fire: Imagining Christian Teaching, is part of the Theological Education Between the Times project.

Find more at: tebt.candler.emory.edu