Like the cover of this issue of In Trust, this article opens by posing a question to you the reader:

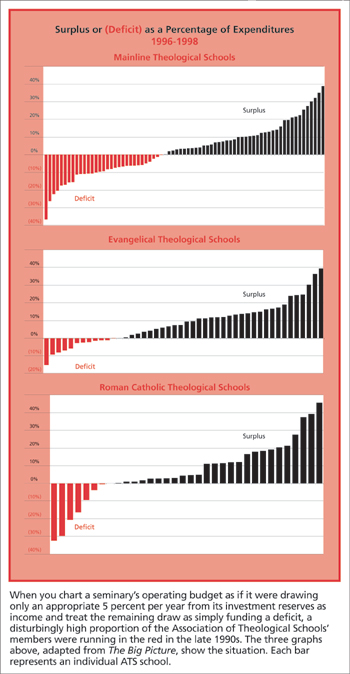

Is the theological school you serve one of the fifty-one Association of Theological Schools seminaries charted on the right whose operating budgets are in persistent deficit? Each red bar dropping below the zero line represents a school in the red.

If your school has an endowment or other long-term reserves, your financial reports may not show any deficit–they may even suggest your school is running in the black. Investment experts recommend that withdrawals from endowment and long-term reserve funds be limited to no more than 5 percent per year of the total principal held. Organizations in difficulties sometimes transfer and label as “operating income” significantly more than this percentage, however, thereby eliminating the red ink. The Big Picture, a recent report published by the Auburn Center for the Study of Theological Education from which the three charts are drawn, doesn’t identify the individual schools portrayed. It’s up to you to find out which bar pictures your school. But the report warns emphatically: “Because standard accounting practices permit this, boards and other overseers must monitor these ‘adjustable” revenue sources carefully.”

The Auburn bar charts use the data schools reported to the ATS for 1996, 1997, and 1998, sorting them into comparable operating income and expense categories and limiting each school’s reported income from investments to the recommended 5 percent of principal. Any school’s performance may have improved (or deteriorated) in the three years since the time period analyzed, but, taken as a whole, the charts depict a community whose financial health is distinctly fragile.

Avoidance Made Easy

|

| Surplus or (Deficit) as a Percentage of Expenditures |

The past decade’s surging stock market made it easier for financially shaky schools and other nonprofit institutions to ignore or minimize to themselves and others the riskiness of their situations. A steady increase in the value of almost all institutional portfolios provided cash to more than make up for shortfalls elsewhere. That reliable stream of new money abruptly dried up last year with the bursting of the internet dot-com bubble and a general weakening of the economy. Many nonprofit organizations face the possibilities of grim days ahead. Some, perhaps many, theological schools are among them.

While twenty-two of the 237 schools supplying financial data to the ATS for the 1999-2000 Fact Book reported long-term holdings of $500,000 or less, even schools with no significant reserves usually have assets, often their buildings and the land on which they sit. At what moment in a school’s life must the governing board and president review in depth how the school pursues its educational mission and decide whether it is making the best use of its assets?

Craig Dykstra, vice president for religion of the Lilly Endowment, a longtime supporter of strengthened governance for theological schools (and of this magazine), raised precisely this point in a recent conversation. If the leaders of an organization in decline fail to realize this fact and act on it, assets that could be used to reinvent the organization and redirect it into more useful pursuits may be frittered away keeping alive lesser programs that soon will die anyway.

An Alarm Bell Heard

One school whose president and board recognized warning signals and have begun to act on them is venerable Union Theological Seminary in New York. Union’s president, Joseph C. Hough Jr., who took the post two years ago after many years as dean of Vanderbilt University Divinity School, said three factors combined to force the board and him to take drastic action: the purchasing power of Union’s endowment income was shrinking despite the bull market; cutbacks in the acquisitions budget of Burke Library, the nation’s largest theological library, were weakening its contemporary collection to an unacceptable level, but there was no place to put the new books if former spending was restored; and long-deferred maintenance of the physical plant could be deferred no longer.

Union’s leaders determined that the seminary would reinvent itself in full view and with the participation of all its constituencies. The Spring 2001 issue of In Trust reported that Union faced a 22 percent deficit this year in its $14 million operating budget, a shortfall Hough characterized as “an unsustainable situation for any institution.”

One model for a new Union that Hough has proposed for consideration by the twenty-one-member strategic planning committee now at work would shrink the full-time faculty from twenty-three professors to twelve. In this model Union would have no more than sixty students in its two master’s programs, a three-year M.Div. curriculum and a two-year M.A. curriculum. The school this year enrolled 185 master’s students and eighty-nine Ph.D. students. The “new Union” will likely admit a dramatically reduced number of Ph.D. candidates, whose programs are significantly more expensive to offer and administer. Just how far the school will be forced to diminish its Ph.D. program remains to be seen. Historically it has been one of the principal North American sources of theological school professors.

In advancing his vision, Hough has stressed repeatedly that his intent is to float ideas, not to force solutions. Union’s faculty, which a decade ago blocked a somewhat similar “rethinking” of the seminary program, signaled a willingness to take an active part in the new deliberations with its February proposal that accepts and builds on most of Hough’s points. A key element of Hough’s vision is making the city of New York and its vast resources an integral element of the curriculum. For example, a class in church history might take a guided visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to see one of the world’s greatest collections of medieval and Renaissance Christian art. Significantly, the major cost of the experience would be the $3 subway fare, which students might well pick up themselves.

The preamble to Union’s constitution adds “enlightened experience” to the mix of “solid learning” and “true piety” typically undergirding theological education curricula for most seminaries. “For a variety of reasons, the focus on learning from ‘enlightened experience” in the heart of the City was never fully explained, institutionally developed, or modeled,” the faculty proposal said, and it endorsed doing just that:

The entire educational program of the Seminary will utilize action-reflection and a rich variety of other educational models to help students understand how diverse communities actually function in the contemporary world and how students can best work within them. For example, instruction relating to the Bible will be as sensitive to helping students understand how diverse communities actually . . . use the Bible as it will be in helping students achieve a deep knowledge of the biblical texts themselves. . . .Throughout, the Union curriculum will utilize the resources of life and work in New York City–as a paradigm of both the challenges and opportunities of the new millennium. . .

In a significant break with the past, the faculty document pronounced firmly that the academic four-department model of theological education–Bible, church history, theology, and practical/pastoral skills–would have to be “discarded.” Future professors will need to cross the divides between academic disciplines easily and teach practical applications concurrently.

Hough envisions supplementing the central curriculum by the creation of several self-funding (through endowments to be raised) institutes staffed by visiting professors. They will offer students courses for credit and also create revenue streams by creating and offering lectures and conferences to the public.

Whatever the outcome, Union must raise significant new endowment funds to reinvent itself. Hough acknowledges that to do this the adopted plan must be imaginative, persuasive, and really new.

Another Warning Heeded

Another theological school’s governing board, the trustees of tiny Swedenborg School of Religion in Newton Centre, Massachusetts, the seminary of the Swedenborgian Church (General Convention), wrestled for three years with how best to respond to the school’s declining enrollment and deepening financial pressures. Its collaboration with Andover Newton Theological School, begun two decades earlier, no longer was working very well, and there were continuing conflicts among Massachusetts Swedenborgians. (The entire denomination is minuscule, currently recording only 1,965 members in the United States and Canada.) Convinced that the school needed to continue to be aligned with a larger theological institution to offer a substantial course of study to prospective Swedenborgian ministers, the board explored a dozen possible sites, said Jane Siebert of Pretty Prairie, Kansas, the chair. After studying the options with the help of consultant Robert Reber, retired dean of Auburn Theological Seminary, the board made a dramatic move. “We needed to stop trying to do it all ourselves,” Siebert said. Two of the four faculty members in Massachusetts retired; termination agreements were negotiated with the other two. The school became the Swedenborgian House of Studies at Pacific School of Religion in Berkeley, California.

Kimberly Hinrichs, a recent PSR graduate who is program director of the new operation, said the house of studies will enroll six students in the fall, including two M.Div. candidates. She regards it as almost providential that the school’s 40,000-volume library exactly fills the shelves left vacant when the PSR library was transferred to the unified Graduate Theological Union library across the street. The students will pursue most of their course work at PSR and other GTU schools, and acquire their knowledge of Swedenborgiana under the auspices of the house.

|

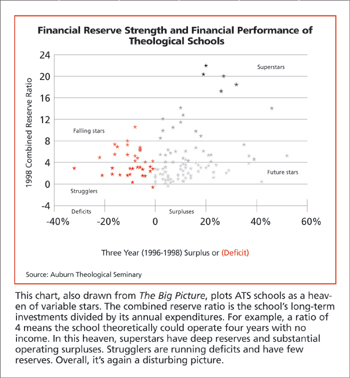

| Financial Reserve Strength and Financial Performance of Theological Schools |

Interim dean of the Swedenborgian House of Studies is the Reverend Jim Lawrence, pastor of the Swedenborgian Church in San Francisco, who acquired his M.Div. degree from Brite Divinity School of Texas Christian University and became familiar then with Disciples houses of studies that the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) maintains at several interdenominational theological schools around the country.

The Swedenborgian board has already sold the school’s campus in Massachusetts and added the proceeds to its endowment (reported at $5.4 million in the 1999-2000 A.T.S. Fact Book). Most of the costs of the transcontinental move and a significant upgrade of the library were funded by a $704,000 grant from the Teagle Foundation of New York.

(To read a follow-up article on how things turned out for the Swedenborgian House of Studies, see New Year 2004’s “Preserving Particularity in Partnership.”)

Merger No, Federation Yes

A redirection of longer standing is the 1997 federation of two Presbyterian institutions, Union Theological Seminary of Richmond and its long-time neighbor the Presbyterian School of Christian Education. Back when only men were ministers of what is now the Presbyterian Church U.S.A., PSCE’s role was to educate Presbyterian women for the only church profession to which they could then aspire: director of religious education. Similar schools operated in other denominations.

As the ministries of mainline churches and their seminaries began to open their ranks to women and students who weren’t candidates for ordination, the clearcut role of schools of Christian education began to fade. Those of many denominations quietly closed their doors. The faculty and board of PSCE soldiered gamely on, proud of their tradition and distinctive curriculum.

“PSCE graduates were deeply loyal,” recalled Freda Gardner, a board member of the school in its closing years of independence. “They had a real sense of gratitude for what had happened to them as students.” Gardner, herself a PSCE graduate and a retired member of the Princeton Theological Seminary faculty, led the five PSCE board members who negotiated the agreement between the schools with the counterpart five-member team from Union’s board.

“We had to ask ourselves, ‘Why are these two institutions existing side by side?”” Gardner said. “It seemed like poor stewardship. . . . The [PSCE] faculty was living sacrificially in a way that was not appropriate.” Indeed, PSCE’s teachers were paid substantially less than their Union colleagues, even though most had been at the school a very long time.

The two schools had already developed a common food service and a shared library. Why should they go on any longer duplicating services and depriving the students and faculty of PSCE, by far the poorer school, of the resources that closer collaboration might bring?

The joint committee set to work, aided by three consultants funded through a Teagle Foundation grant: Ellis Nelson, a veteran of Presbyterian institutional governance; Laura Lewis, a professor of Christian education at Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary; and Anthony Ruger of Auburn Seminary, an expert on seminary finance. “We had no interest in spending a lot of time talking with no resolution,” said Taylor Reveley, dean of William and Mary College Law School, who led the Union team. They decided quickly to act, establishing ground rules for their discussions–perhaps most important that committee members would speak openly about their concerns rather than sit silent in meetings then go out and speak elsewhere. “I thought this was crucially important,” Reveley added.

PSCE had few financial assets beyond its real estate–buildings precious to the school community but including a dormitory that was about ready to fall down–but representatives successfully conveyed their passion for the school’s history. “A massive effort was made by everyone to prevent PSCE from just disappearing,” recalled Reveley. The goal was “not merger but marriage.” “Federation” soon was used to describe the relationship being hammered out. While PSCE’s negotiating goal was retention of some kind of continued life, Union’s was to avoid terms that would establish an unending financial liability.

In a relatively short time an agreement emerged that was acceptable to both boards and, perhaps more important, both communities. The faculties and (more easily) the boards were merged, a portion of PSCE’s campus was sold to the Baptist Theological Seminary at Richmond, and Union’s Louis B. Weeks became president of the extensively named Union Theological Seminary and Presbyterian School of Christian Education–which the school’s telephone operators have learned to say in one breath.

The Future of Your School

If you serve on a theological school board, you the reader now must write the rest of this article, because the financial, operational, and spiritual details that characterize your school are in your hands. A good start is contained in the Strategic Information Report, which is in the hands of the chief executive of every A.T.S. school. Vincent Cushing describes how to use it in this issue’s “Toolbox.”

As you and your fellow board members reflect on the future of your school, which should be a major activity of all boards, read the signs of the times in your financial numbers. If your school’s position in the seminaries” heaven shown in the chart to the left is among the strugglers, you may not have much time to reconceptualize your mission into something that will extend your future.

Resource

The text of The Big Picture: Strategic Choices for Theological Schools, which is referred to in this article, may be downloaded from www.auburnsem.org.