For the typical middle-class North American, the family home is the most significant asset. Pension plans and investments are good, and saving for a rainy day is admirable, but in the end, there's nothing like owning a home debt-free.

But what about theological schools? To pursue their missions, do they need to own their homes? And when the rainy day arrives, how do they know when it is time to tap into the ever-growing value of real estate?

Tracking the total revenues for 220 schools from 1996 to 2005, data from the Association of Theological Schools show that schools took a substantial hit in the first part of this decade. The drop in total revenues paralleled the stock market performance for those years, and many schools had to take an even harder look at their budgets — especially if enrollment growth was stagnant and individual giving could not make up the difference between income and rising expenses.

Recently, a number of North American theological schools have faced their financial challenges head on and have decided, reluctantly or not, to sell. Their stories are hopeful — and sometimes painful.

A way up

|

| Denver Seminary |

When Dr. Craig Williford signed on as president of Denver Seminary in August 2000, he found himself at the helm of a campus that needed some work. Deferred maintenance had built up over the years, and it was clear that a lot money needed to be spent, and soon.

The campus of the nondenominational, evangelical school was a very valuable piece of land in Denver, so the school had been hearing from developers who wanted to purchase the property. "We had a decision to make," said Williford — whether the seminary was going to pour millions of dollars into maintenance and repairs that had long been deferred. To do so would bring it up to speed but leave no room for growth, no major remodeling, no new building projects.

|

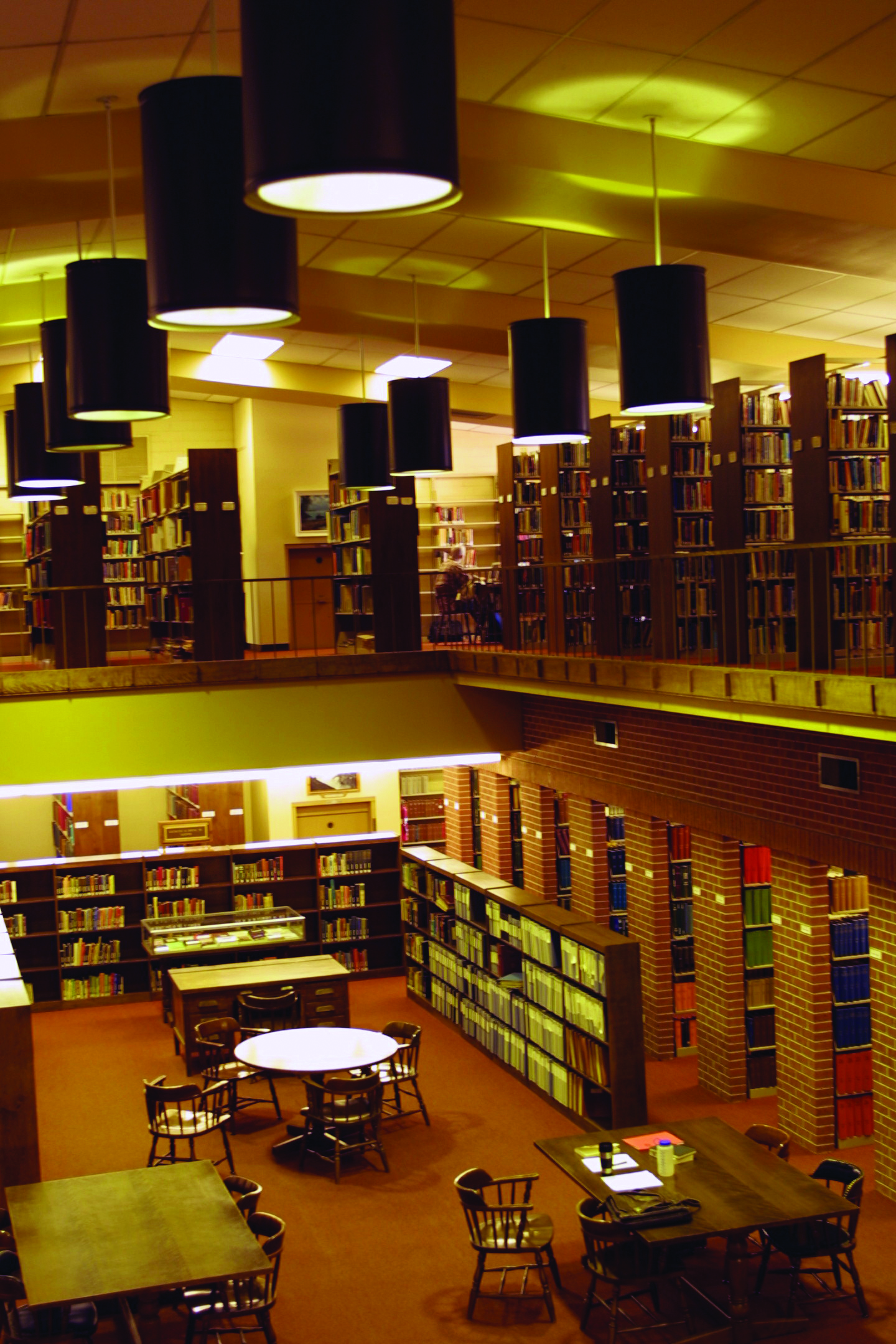

| Denver Seminary’s new Carey S. Thomas Library is just one part of an entirely new 20-acre campus, completed in 2005, that encompasses seven buildings. The new property cost $3 million, and construction costs totaled $23.5 million. Denver’s old campus (including the former library, inset) was sold to a developer for $12.3 million. |

So the school started exploring the idea of selling the campus, with the aim of using that money to build a new campus. "We felt our constituents would be more excited about that," said Williford.

Right from the start, the president and board broke the process down into a series of smaller decisions. "The first thing we did was put together a joint task force of board members and leaders of the seminary to discuss if the seminary should consider moving," said Williford. "Then after that piece, we said, 'If we are going to move, then to what?'"

The board was involved at all stages of the process. In fact, board members, faculty, staff, and students all served on the committees that moved the process forward — finance, design, and relocation committees, and more.

An important issue was emotional attachment. At any seminary, people become invested in the school over the years. Students have fond memories of living in the dorms, couples reminisce about weddings in the chapel, and professors teach in the same classrooms for years or even decades. Leaders in administration and on the board have the challenge of communicating the primacy of a school's mission over its actual physical address.

Denver Seminary had a champion in the person of Dr. Vernon Grounds, who early on endorsed the school's decision to sell the old campus and move. For more than 56 years, Grounds has been a part of the seminary's life, serving as dean, president, and now chancellor. "All of the emotional attachment and the historical attachment to Denver Seminary are tied to him as an individual," said Williford. His endorsement, therefore, went a long way in diffusing resistance to the move.

Communication was a key part of the process. The administration and the board spent four years meeting with key leaders individually, in small groups, and in larger groups. "We took every chance we had within the community, within our donor base, within our student body, within our faculty and staff," said Williford, "constantly selling the vision and the story of why this made sense and what God might be doing in all this."

A way out

|

|

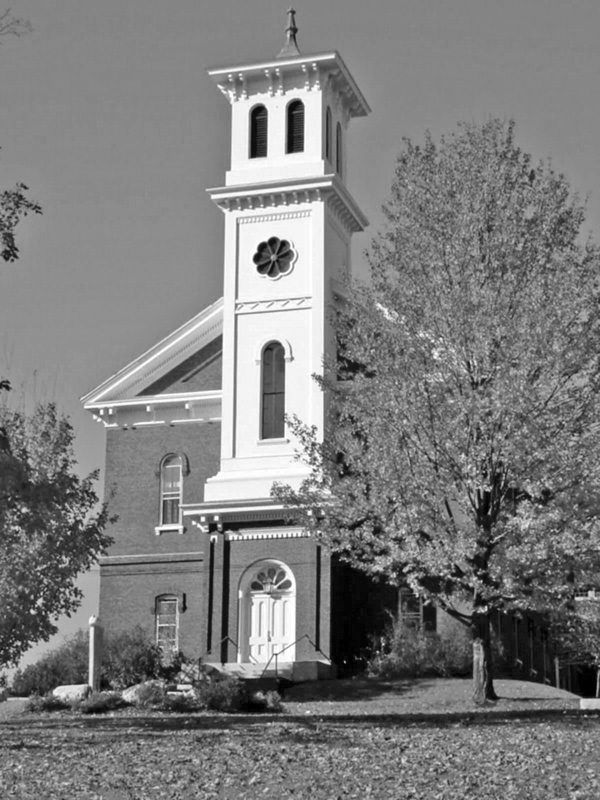

Two years ago, Bangor Theological Seminary moved from its historic 19th-century grounds in Bangor, Maine (inset), to the nearby campus of Husson College. Cutting expenses has enabled the school to decrease its endowment draw-down from 9.7 percent to 6.4 percent.

Bangor Theological Seminary |

Not every seminary will take a look at their property and discover a pot of gold. Often the impetus to move is not a decision about how to best spend assets in hand, but rather how to save money and salvage a school's mission from increasing financial pressures. This is the story at Bangor Theological Seminary in Maine.

When Dr. William Imes became president of the United Church of Christ-affiliated school in 2001, he was faced with a situation that is not uncommon for theological schools. "We could not afford to continue living as we were, because we were living beyond our means," said Imes. "I entertained the notion that we are a good school, that there must be ways that we could grow out of our troubles. I felt that what we were doing was good, and I didn't see our budget as extravagant, so I saw the question as how we could generate more income."

They looked at raising the endowment, increasing giving, and attracting more students. Over the next few years, they saw some increase in income, but by autumn 2004, things had not turned around significantly. The enrollment that semester — the highest number of incoming students in years — was first seen as a sign of progress. However, the new students only increased Bangor's FTE enrollment by two-tenths of a percent, because many of the new enrollees were part-time students.

Imes became convinced that Bangor was not going to grow its way out of its troubles. Having asked the board for deficit budgets since the beginning of his tenure, he went to the board of trustees to explore ways to cut expenses. He talked to many people about the problem, including the president of nearby Husson College, Dr. William Beardsley. Husson College, founded in 1898, has been at its present campus in Bangor, Maine, since the 1960s. Together, Beardsley and Imes considered the idea that Bangor Seminary could build a new building on the Husson campus and move there. This would reduce the size of their campus dramatically — a move that made sense for a seminary moving away from a traditional residential model.

|

| Bangor Theological Seminary |

While Imes was busy talking to trustees, faculty, staff, and alumni about this idea, Beardsley came back to him with a new proposition. Husson College was moving its nursing department to a new building, and the newly vacated building might serve the purposes of the seminary. The seminary went from seeing if they could work toward a move in two years to needing to make a decision immediately. "My first response was Good grief," said Imes. "We're just like a church: we have to circle a problem six times before we can land on it. And now you're asking a business sort of decision — here's an opportunity, take it or miss it."

Once Imes looked at how much they could save immediately, it became clear that he needed to persuade people that this was something the school needed to do. The trustees and faculty were on board right from the start. But some of the staff, students, and alumni were appalled that the seminary would leave the campus it had occupied since 1824. "I don't know if having two years to think it over would have made it any easier," said Imes. In any case, the immediate decision to move raised a lot of questions.

The decision was made within a month, and the seminary moved to the Husson College campus in autumn 2005. The school took two more years to come up with a plan for selling the old campus. The sale to a developer is expected to be completed this summer.

The effect the move had on Bangor Theological Seminary's finances has been significant. With the sale of their property this summer, the draw off the endowment, which had been around 9.7 percent, will drop to 6.4 percent. Next year, the draw will drop to 5.4 percent, closer to the 5 percent recommended by investment managers to ensure the long-term value of an endowment.

Though there was interest in building at the start of the process, Imes said he would now like to continue to lease. Realizing how an increased endowment can help fund the seminary's programs, Imes has a simple question: "Why do I want to put money back in building?" Nevertheless, he is aware that more efficient, less expensive facilities do not solve all the school's financial problems. There is much work to be done to move Bangor toward greater economic stability.

A way forward

|

In two transactions, Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary first acquired a 24-acre parcel and later sold 30 acres of vacant campus land to a real estate developer, leaving the school six acres smaller, but $6.8 million and one building richer.

Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary |

The sale of property is not always motivated by a deteriorating campus or a need to restore financial stability to an institution. In some cases, the purchasing and selling of property is part of a larger investment strategy. Such is the case with Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, a Southern Baptist school in Kansas City, Missouri.

Dr. R. Philip Roberts, president of Midwestern Baptist, said the decision was a development question, and what really freed them up to sell the property was a previous real estate purchase. Back in 2002, the seminary's trustees approved the purchase of the 24 acres adjacent to the seminary. The property, which sold for $1.4 million, included a 34,000-square-foot building that had been used as a corporate retreat center by Farmland Inc. It has since been renovated and is being used as a general-purpose building.

This year, the seminary is poised to sell 30 acres of vacant property on the other side of its campus for $8.2 million — money that will go to grow the endowment and fund future building projects. All told, in a five-year period, the campus is six acres smaller, but the seminary has gained $6.8 million and a significant building.

The sale of the property to real estate developers is nearly complete, and a 300,000-square-foot retail center called North Oak Village is planned for the site.

Before the sale, Midwestern Baptist owned more than 200 acres, and "we were obviously swimming in a lot of land for a seminary," said Roberts. "We thought this was a smart move and a good chance for us to do some of the projects we are working on."

Acquiring the 24 acres back in 2002 was a project the administration spearheaded — they brokered the deal and essentially got board approval to proceed with the purchase. Once they bought that parcel, however, they established a land use committee to look into the possibility of selling off some other acreage.

"It's a very busy retail corner, so we knew there was a lot of potential — we've had constant appeals and approaches made to us about selling it," said Roberts.

In order to streamline the process, the school engaged a negotiator who helped with vetting the appeals. Qualified offers were then passed on to a committee of trustees who reviewed those elements and brought a proposal to the board for the sale of the property.

A number of people did approach the school about selling the entire campus. But to move, they wanted enough money to build another campus with the same square footage and acreage. "They suddenly lost interest when we let them know how generous an offer we expected," said Roberts wryly. For now, the proceeds from the property sale will help Midwestern stay put — and focus on its mission.

Real estate and good governance

Issues that boards and administrators may want to consider before selling:

➤

Mission. Are we clear about the mission of our school? Does our current property enhance our capacity to pursue our mission with economic vitality? If we sell all or part of our property, what will we do with the proceeds of the sale to strengthen our mission and make us economically stronger? Explore as many ideas as possible.

➤

Relationships. Which members of the seminary community should be part of the planning process? How will the views of various constituencies — faculty, denominational partners, students, alumni, church leaders, neighbors — be taken into consideration? How will we communicate during the process and how will we position our decision?

➤

Costs. What are the annual costs of keeping our current property, including needed capital improvements, routine maintenance, loans and interest, and energy requirements? What are the estimated annual costs of an alternate campus? What are the estimated one-time costs of moving, including lawyers' and brokers' fees?

➤

Real estate market. Are we currently in a buyer's market or a seller's market?

➤

Benefits. What are the nonfinancial benefits of staying on our existing property? What are the nonfinancial benefits of moving to a new campus?

➤

New neighbors. If we're considering selling only part of our property, what kind of neighbors are we seeking? Will the property need to be rezoned?

➤

Calendar. What time restrictions are we facing?

➤

Experts. What kind of expert advice do we need to move forward? Appraisers? Brokers? Attorneys? Others?

Seminaries on the move

Sioux Falls Seminary

|

|

Sioux Falls Seminary is planning a new building adjacent to nearby Augustana College.

Sioux Falls Seminary

|

Faced with mounting debt and a poll revealing that only 11 percent of the students desired campus housing, Dr. Michael Hagan, president of Sioux Falls Seminary in South Dakota, felt the door was open to consider the school's properties as assets that could extricate the seminary from its financial difficulties.

Trustees at the school, which until this year was called North American Baptist Seminary and is affiliated with the North American Baptist Conference, considered selling only parts of the property, but eventually they sold the entire campus to Sioux Valley Hospital, located across the street.

Sioux Falls Seminary is now leasing the campus back from the hospital. In 2008, the school will break ground on a new building adjacent to Augustana College, just a few blocks south of the current location. Though the seminary will have its own campus, it will borrow some of the college's facilities as well. Augustana has agreed to let seminary students live in their married housing, the seminary's books will be housed in a special section of the college library, and the college chapel will be used by the seminary for biweekly chapel services.

Central Baptist Theological Seminary

Two of the things that Dr. Molly Marshall knew must be addressed when she became president of Central Baptist Theological Seminary in Kansas City, Kansas, in 2004 were seriously deferred maintenance and the inappropriate configuring of learning space for adult learners. So she appointed a board task force to consider the decision to sell and relocate.

|

Central Baptist Theological Seminary’s new home in Shawnee, Kansas.

Central Baptist Theological Seminary |

In November 2005 the task force reported that relocation would be necessary for the American Baptist-affiliated seminary to continue to grow its financial resources to support its mission. The committee recommended that the school purchase a new property in nearby Shawnee, Kansas, in May 2006.

Throughout the process, Marshall met with different groups to explain the move, listen to concerns and get the support of faculty, staff and the seminary community at large.

Moving to the new building in August 2006 created challenges: International students, who relied on campus housing, were allowed to remain in their apartments on the old campus, and space had to be leased to house the school's library collection because the new building did not have the proper space.

The Kansas City campus is expected to sell this year.