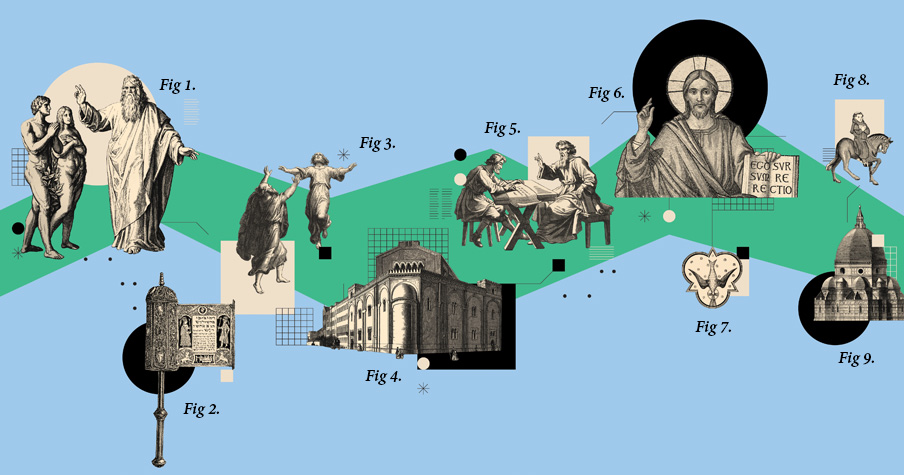

Fig 1) Word: First theological instruction, directly from God – a primer on spiritual discipline and a call to obedience. | Fig 2) Law: Torah, ascribed to Moses by God: divine revelation, and source of authority for formation. | Fig 3) Prophets: Proclaimers of the Word of God; harbingers of a consuming fire and the promise of God’s salvation. | Fig 4) Worship: Temples and later synagogues become places of worship, havens for assembly and sites of religious education. | Fig 5) Scribes: Interpreters and teachers of biblical law; initiators of the tradition of religious scholarship. | Fig 6) Savior: An itinerant healer and teacher who modeled sacrif ice and love. Fully human, fully divine. | Fig 7) Holy Spirit: The unhindered activity of God that descends on disciples, creating and revitalizing innovation. | Fig 8) Monastics: Pious monks created orders for education that blossomed even through plagues. | Fig 9) Cathedrals: Expressions of faith, channels of creative visual energy, cathedrals provide spiritual education and inspiration for connections with God. | Illustrations by Israel G. Vargas

Even after surviving two years of a pandemic, it’s still difficult to perceive clear lessons learned for theological schools across North America. The things that might seem clear (and non-controversial) are those that could have been learned by a child or are just good common sense: Wash your hands, cover your cough, and give people a little bit of space.

The pandemic swept around the globe so quickly and with so many variations that it was difficult to see or predict. In February 2020, would anyone have been able to anticipate what has happened since then? It wasn’t a lack of foresight or preparation – it’s doubtful anyone had “global viral pandemic” in their emergency response plans. It would have taken prophetic insight to be ready.

While there were some universal experiences, such as masking and online learning, the way schools experienced the pandemic largely depended on their locations. In Canada, schools saw a repeal of masking requirements just this summer. In the United States, the regulations differed depending upon local and state health departments. As a result some schools opened their campuses to in-person learning in the fall of 2020 after taking time away in the spring. Other schools have had campuses largely empty until the federal repeal of many safety measures earlier this year.

Given these experiences, in discussions with theological leaders across North America and in the work of the In Trust Center, there are some broad conclusions about what schools are learning from the pandemic.

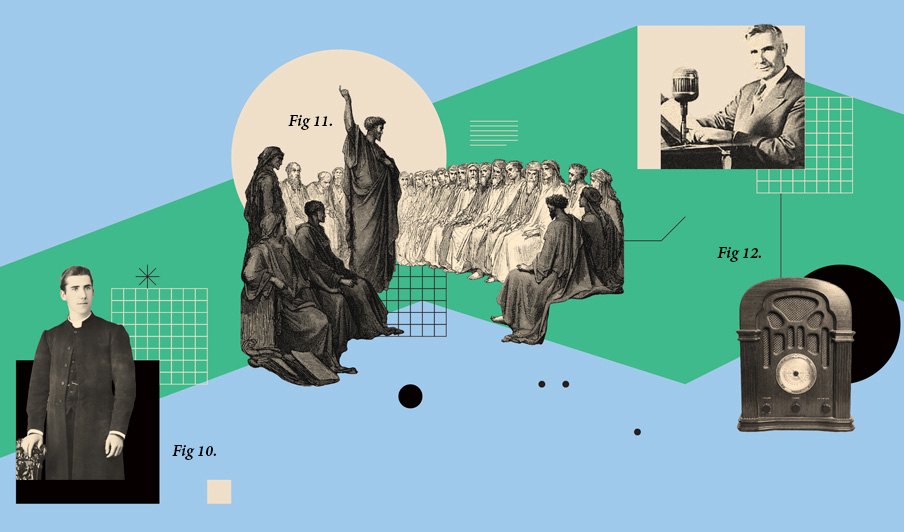

Fig 10) Clergy: Ministers, pastors, and priests of all denominations have brought communities of faith into greater communion with God. | Fig 11) Preachers: Awakenings and revivals have provided intellectual and spiritual leadership for centuries. | Fig 12) Radio: Evangelist Charles Fuller was among the first to see the potential of radio to reach a wide audience. The success of his Old Fashioned Radio Hour led to the founding of Fuller Seminary 75 years ago. | Illustrations by Israel G. Vargas

The issues are still the issues

The world may have turned upside down, but the issues facing theological schools haven’t changed. In many ways, they may have grown.

In his address at the Association for Theological Schools’ business meeting in June, which was held online before the in-person Biennial, ATS Executive Director Frank Yamada, Ph.D., addressed the situation directly to a live audience and online:

“The pandemic exacerbated what we’ve already known: Theological schools are facing significant stresses in multiple ways.”

The enrollment increase that came as a result of the pandemic – fall 2020 saw a boost – quickly diminished. By the following year, there was a return to the persistent pattern of the last decade , which has seen a long, slow decline. That is much the same as it has been in previous economic crises, which saw short-term bumps in enrollment, only to watch them recede again.

Schools are still grappling with flagging enrollment, issues of deferred maintenance on campus, the appropriate size of the campus, new technologies, and changing pedagogies, along with issues of governance and even mission, as in, should the mission change to meet the times?

Again, while the particulars have changed with the times – including internal debates over doctrine – the underlying issues aren’t news; they’ve been discussed, debated, and written about for years. Many schools found relief in federal emergency funds that helped budgets through the initial shock of the pandemic. But those funds are long gone, and the pandemic laid bare the realities facing schools in sobering ways.

The speed of change

The swiftness of the pandemic, along with the quickness with which educators had to act, certainly showed schools a few things.

Many schools have struggled for years to move to online programs, and some had moved cautiously due to concerns over technology and pedagogy, as well as issues of quality and spiritual formation. Several faculties were reluctant to move to an arena that they perceived would diminish quality, particularly in formation. Many schools lacked what they thought they would need in terms of technology or a technological infrastructure.

“After all that, we were fully online in two weeks,” one leader said flatly.

Indeed. Schools found ways to quickly move to online education, even if it wasn’t the quality they wanted at the outset. Chapels, classes, discussion groups, prayer sessions, and formation visits were all conducted online through smart phones, laptop cameras, other technology, and a variety of apps.

So, if there’s a lesson learned, it’s that digital learning is doable. The speed and cost of moving online are certainly in reach. While the quality of video production matters, many schools found that the concerns about whether they had the right equipment weren’t as significant as they thought – at least just to get online. The questions that remain for many schools are about best practices, what quality looks like, and how to conduct meaningful formation work at a distance.

Fig 13) Television: The rise of televangelism in the late 20th century reached millions of the faithful, and introduced countless seekers to the Word of God. | Fig 14) Recordings: Evolutions in analog media brought the Word directly into the home, enabling ownership and nearly unlimited access. | Fig 15) Podcasts: Vehicles for thought and exploration, a medium that invites, challenges, and engages a worldwide audience. | Fig 16) Streaming: Subscription-based content provides unparalleled access. Can it accomodate the context and sustained attention necessary to engage fully with the Word? | Illustrations by Israel G. Vargas

The focus is still people

Some institutions have struggled with the difference between online and in-person education, not only in the pedagogy but also in the way they relate to students. Several academic leaders have struggled against the perception that there are different types of students.

One railed against people being called “virtual” and said, “They’re not virtual students, they’re students – they’re people!” Several leaders said there remains a need to strengthen the student experience online and to improve ways to educate students.

The issue is how to better interact with students and create paths for spiritual formation, which has long been at the heart of a seminary degree. How that happens in practice is an issue with which schools continue to experiment – some opting for hybrid, in-person retreats, other opting for mentors who live near students.

“It’s not a question of if we can do it, but how we best do it,” said one leader in distance education.

After all, the work of theological schools – and their graduates – is focused on people. The lack of people on campus dramatically changed the feel.

“There are only a few people on campus,” one leader said. “It gets lonely around here.”

That sense of loneliness and change – along with the stress of the pandemic – has been part of several leaders considering leaving or retiring.

There have also been changes at the faculty level, as some faculty members have sped up retirement plans or moved on to other things after several tumultuous years of the pandemic and the rapid changes in the field.

The focus on people is playing out internally, as well. Several leaders discussed different ways of self-care, and practice spiritual disciplines as a way of renewal.Others noted that although seminaries teach those things, the administration, faculty, and staff don’t always practice them well, noting that the stress has taken an increased toll on people’s well-being.

A recent ATS study on leadership found that more than half of new Chief Executive Officers felt only slightly or somewhat prepared in self-care. ATS studies on both CEOs and chief academic officers noted that poor self-care and spiritual disciplines led to burnout (see related story, p. 5).

Fig 17) A new reality?: As virtual reality evolves, will new ways of teaching, learning, and proclaiming the Word emerge? | Illustrations by Israel G. Vargas

Space is changing

The move to online education has affected the way leaders are viewing education. For example, one school noted that their enrollments between online and in-person students flipped. Before the pandemic, the overwhelming majority of students pursued their studies in person, but with long restrictions against on-campus meeting, enrollments – even after restrictions were lifted – are now overwhelmingly online.

That’s much like the workforce generally. Many white-collar workers have found that working in hybrid or remote workspaces is far more preferrable to the daily office grind and the rising financial and personal costs of commuting.

While education leaders don’t know what the numbers of online students will be, the expectation is that it’s a trend that will certainly hold. As a result, campus leaders are either downsizing or considering doing so, particularly with rising costs of deferred maintenance on older buildings.

Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary, for example, sold about half its campus, including a residence hall that was well past its prime. In Chicago, McCormick Theological Seminary and the Lutheran School of Theology this year announced a plan to sell to the University of Chicago. Religion News Service reported that in the past dozen years, at least eight other schools have sold or downsized properties.

There are discussions at many campuses about what future space will look like, and some are debating what their missions will look like and whether they should adapt those to the times to entice new students.

A hope for the future

These are all weighty questions, but Yamada remains positive. He noted that schools are seeking long-term solutions to the struggles they’ve faced.

“The good news in all of this is that schools are adapting,” he said. “Schools are changing in intentional and strategic directions in order to carry out their educational missions in more sustainable ways. This is timely and appropriate.”

He noted that innovation is happening in the field and “boards, administrations, and faculty across the ATS are having conversations about their future.”

Yamada said that some schools are “soberly realistic in their assessment of their current realities, some are hopeful, many are rethinking and reassessing strategies for their futures.”

He said the new ATS standards provide more flexibility for schools to experiment and try new things.

He also pointed to the Lilly Endowment Inc.’s Pathways for Tomorrow initiative, which has put more than $80 million into ATS schools to help them think about and fund new efforts.

There are more than 80 projects in Phase 2 of the grant, which offer creative ways to tackle issues in theological education and its future.

Yamada, an Old Testament scholar, said that in the book of Genesis “God’s creative action happens not in spite of but in the middle of chaos.”

“So, too, are theological schools in this current crisis,” he said. “If there is a lesson I’m taking from this time, it is that we’re in this together.”