Information technology—the catch-all term for how information is transmitted, received, packaged, and processed—has developed dramatically in the last half of this century. In 1953 there were only about 100 computers in use in the entire world. Today hundreds of millions of computers form the core of electronic products, and more than 110 million programmable computers are being used in every setting from great industrial corporations to ordinary homes. Today’s desktop personal computers, or PCs, are many times more powerful than the huge, million-dollar business computers of the 1960s and 1970s. Most PCs—including portable laptops—can perform from 16 to 66 million operations per second, and some can even perform more than 100 million. Computers make all modern communication possible. Local-area networks link the computers in separate departments of institutions, and wide-area networks and the internet link individual computers to other computers anywhere in the world.

When it comes to the field of education, information technology is challenging, enhancing, and changing the way teachers teach and students learn. What were once isolated classrooms with little more than desks and blackboards are now multimedia theaters as well as nodes, or on-ramps, to the information superhighway.

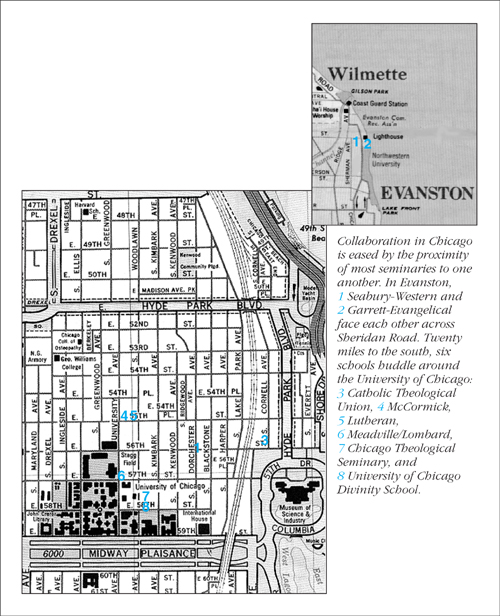

However, even though technology has become more widespread and affordable, it still remains expensive. For graduate theological schools, few of which enjoy the endowments and other funding available to larger private and state colleges and universities, the necessity of smart spending, collaboration, and grants cannot be overstated. Four theological schools in the Chicago area—Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary and Seabury-Western Theological Seminary on the North Side, and McCormick Theological Seminary and Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago on the South Side—have paired their efforts in technological updating and opened ties to other neighboring schools to get the most out of their high-tech bucks. The four schools were all recipients of 1997 grants from the Lilly Endowment to expand the use of information technology in theological teaching.

|

For larger view of map.

view |

Garrett and Seabury

Both Garrett-Evangelical and Seabury-Western are located just north of Chicago on the campus of Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. Each school maintains its own identity—the former is United Methodist and the latter is Episcopal—but both enjoy the tremendous advantage of a long history of sharing resources with each other and with Northwestern, according to Garrett’s president Neal Fisher and Seabury’s director of academic affairs, the Reverend Meredith Potter. The bonds between the three schools go back to 1929 when Northwestern University and what was then Garrett Biblical Institute invited Western Theological Seminary to reside in Evanston. (In 1974 Garrett merged with Evangelical Theological Seminary; in 1933 Western merged with Seabury Divinity School.)

For nearly seventy years students from both seminaries have enjoyed wide access to the life and resources of Northwestern. These benefits include use of the university library, one of the major academic collections in the United States; cross-registration in a number of courses and scholarly disciplines; cooperative degree programs with the Medill School of Journalism and the School of Music; participation in intramural sports; access to sports facilities and Big Ten athletic events; access to the performing and fine arts complex with its year-round calendar of concerts, dance recitals, theater productions, and films; and admission to special lectures in all academic fields.

Garrett and Seabury are members of the Association of Chicago Theological Schools, which comprises eleven major seminaries ranging across nearly the full breadth of North American denominational traditions; the schools’ combined teaching staffs make up the largest concentration of theological scholars in the United States. In the midst of this, Garrett and Seabury have built a special relationship between themselves. “We are right across the street from each other,” explains Potter, “which makes possible coordinated course offerings, some team-taught courses, the United Library, many shared events, and most recently a shared vision for using information technology.”

A major part of Garrett’s and Seabury’s cooperative efforts in the planning and implementation of information technology was sparked by recent grants received from the Lilly Endowment. Fred Hofheinz, an Endowment program director for religion, explained: “When we first conceived of these grants in 1995, we knew that technology was impacting higher education and pedagogy in numerous exciting ways, but we did not know if or how theology lent itself to using information technology. Consequently, we chose thirty institutions that represented a microcosm of the universe of theological schools in terms of size, budget, and focus and invited them to submit proposals for how they would use their grants to implement information technology on their campuses.” Lilly gave each school $10,000 planning grants and then $200,000 for implementation. Hofheinz added, “We also recognized that technology is a springboard to all kinds of collaboration. And we are so delighted with the sharing and partnering that schools like Garrett and Seabury and McCormick and Lutheran School of Theology have embarked on.” (Lilly has selected forty new schools to receive $10,000 planning grants this year and $300,000 implementation grants next year.)

“When we received the grants in December 1997,” explained Garrett’s Neal Fisher, “our project directors [Adolf Hansen, Jack Seymour, and George Kalantzis] sat down with Seabury’s directors [Mark McKernin, Meredith Potter, and Newland Smith] and decided how each school could use the grant for its particular needs while helping the other.” Garrett, for example, had to spend approximately $57,000 on twenty-six laptop computers for its faculty and money from another grant to complete the fiber-optic wiring connections of its facilities to Northwestern, while Seabury had already accomplished these tasks in 1995. But both schools decided that while they would use the period leading up to June 1999 to proceed somewhat independently in implementing their computing, training, and support for faculty, students and staff, they would meet regularly to make plans for turning the United Library into the center of information technology serving the two institutions. “During this time,” adds Seabury’s Potter, “the staff of the United Library has continued developing their expertise. While Garrett and Seabury have each had their own technical consultants, we will eventually share one technical director and a core of technical assistants.”

Bringing Faculties Up to Speed

One of the biggest challenges facing both Garrett and Seabury has been training faculty and students on everything from how to use a computer to how to use software such as Netscape Navigator for the internet and PowerPoint for classroom multimedia presentations. As both schools near their goals of having two permanent and two portable “smart” classrooms—classrooms equipped with computer video capabilities for instruction—it becomes increasingly important that teachers and students know how to make the best use of the technology at their disposal. Pausing to answer a plea for help with a virus-infected document from a stressed-out preacher unable to print her sermon, Potter regained her thoughts and offered: “Because my background is in math and computer science, I handle lots of technical questions. But we have two well-trained students assigned to give fellow students help during two evenings each week in the computer lab, which is open twenty-four hours a day. We also have an excellent part-time technical consultant who is with us three days per week. We had a great deal of trouble finding a good technical consultant early on, but we are quite happy now. And eventually the United Library will be more fully a hub for training in all areas.”

As for how faculty and students are reacting to the new information technology on campus, Garrett’s Kalantzis, director of education technology and assistant professor of early Christianity, said. “They love it.” He added: “Of a faculty of twenty-seven we already have had over half get into training programs so that they can use the information technology as quickly as possible. And the students, a majority of whom are visual learners, enjoy courses taught with multimedia as well as the chance to learn how to use the media for their own purposes, such as developing parish web sites and using the vast resources of the internet to learn.” Seabury’s Potter agreed: “Information technology allows classes to take a field trip to a museum without leaving their seats. It allows them the chance to dialogue on electronic bulletin boards, which gives people, especially introverts and foreign-language speakers, more time to think about their questions and answers. It allows professors a chance to use video and internet resources to enhance their presentations. Information technology is wonderful in many expected and unexpected ways.”

McCormick and LSTC

Located less than twenty miles south of Garrett and Seabury in Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood are McCormick Theological Seminary (Presbyterian) and Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago, a seminary of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. Long-time collaborators, since 1975 these two schools have shared a twelve-room classroom building that LSTC owns, library (the Jesuit-Krauss-McCormick Library located in the west wing of the LSTC classroom building), and housing. In that year McCormick moved from Chicago’s midtown Lincoln Park area to be nearer to the University of Chicago and the Hyde Park cluster of theological institutions that also includes Chicago Theological Seminary, Meadville/Lombard Theological School, Catholic Theological Union, and the University of Chicago Divinity School. (The divinity school chooses not to be a member of The Association of Chicago Theological Schools.)

McCormick and LSTC have a collegial relationship with the University of Chicago that includes joint degree programs such as master of divinity and master of social work; bi-registration for courses for one-half the normal charge; borrowing privileges from the Regenstein Graduate Library of the Arts and Sciences, one of the nation’s leading research libraries; and use of the university’s athletic facilities. But in contrast to Garrett’s and Seabury’s relationship with Northwestern, neither McCormick nor LSTC is connected to the University of Chicago’s technology infrastructure. “It boils down to the fact that the university simply could not absorb our two schools into its technological or staffing infrastructure. But they have been enormously helpful in all of our planning and training for growth in information technology; for example, they have allowed us to do our purchasing of hardware and software through them in order to get considerable cost savings,” said Kurt Gabbard, vice president for finance and operations at McCormick, and Christopher Eldredge, director of information technology for both McCormick and LSTC.

Lacking the benefit of tapping into the University of Chicago’s technological resources has meant that both McCormick and LSTC have had to build their information technology systems from the ground up. Consequently, when they were selected as recipients of the Lilly technology grants, they decided the best way to proceed would be to pool their money and create a joint plan from beginning to end. “When our two schools were selected for the Lilly grants,” explained Gabbard, “each of us created project teams and then came together as one joint project team and met regularly to plan our strategy and agenda. Essentially we combined our grants for a total of $420,000 for everything from infrastructure to training faculty and staff.”

The joint initiative calls for building on McCormick and LSTC’s previous achievements of installing a local area network, securing internet access, and creating web sites, and making the major part of the JKM Library’s catalogue available on line. Plans include upgrading all faculty computers, approximately twenty for each school, to state-of-the-art laptops; combining LSTC’s already existing Language Resource and Learning Center with the JKM Library and computer laboratory; creating up to seven smart classrooms; and broadening the mission of the JKM Library by training the research librarians to provide support for the faculty in using technology for teaching, learning, and research. The combination of LSTC’s and JKM Library’s facilities allows them to combine equipment purchases and enhance the use of and training in electronic resources.

“What has been most beneficial about the technology grant is that it serves as a catalyst for further collaboration between the two schools,” said McCormick’s Gabbard. “In fact, we are now discussing a plan for McCormick to build an administration building on LSTC’s campus.” What has also strengthened the collaboration between the two schools has been the recent Formula of Agreement, a formal pact that brought the two sponsoring denominations into full communion with each other and recognized each other’s ordinations. “We are treading on new territory where a Presbyterian seminarian could end up serving in a Lutheran parish or vice versa,” added Gabbard.

As is the case with Garrett and Seabury, McCormick and LSTC have found that the most challenging area of information technology is training faculty and staff. Ralph Klein, former dean and one of the project leaders for information technology at LSTC, said, “When it came to training faculty—McCormick has thirty and LSTC has twenty-three full-time faculty members—how to use their new computers and the many different software packages available to them for teaching purposes, we had to hire a technical person who also understands the nuances of teaching, especially in the field of theology. We decided to hire Christopher Eldredge, who now serves both schools and has a terrific background.”

Interestingly, Eldredge is not trained as a computer specialist. He is a Lutheran pastor who graduated from Christ Seminary-Seminex, St. Louis, Missouri, before it merged with other Lutheran schools and became LSTC. Eldredge came to Chicago in 1983 and has been director of the office of student life, the office of admissions, and fundraising at LSTC. In 1995 he became director of information technology for LSTC and in 1997 assumed the position of director of information technology for both McCormick and LSTC.

As one who understands the complexities of the new technology and the demands of teaching, Eldredge’s days are filled with varied and countless tasks that include overseeing the Informix-based administrative system, working with faculty members on multimedia presentations and distance learning, helping the communications departments from the two schools develop their web sites, and budgeting. Eldredge also does a lot of what he calls “triage”—making flow charts of pressing issues and discerning action strategies for addressing them. Though he is a non-teaching member of LSTC’s faculty he and his team will teach a course on technology and its use in parish ministry.

Eldredge’s team consists of the recently merged information technology staffs from both schools. Presently there are four technicians in addition to Eldredge—a networking and server specialist, a desktop specialist who focuses on training issues, a desktop support and communications specialist, and the director of technical services for the JKM Library. The team is now looking for an administration applications specialist who will enable the schools to operate with standardized hardware and software. The goal of such collaboration fortifies McCormick’s plan to erect a new administration building on LSTC’s campus.

Collaboration has been a hallmark of the spending decisions of a number of the Lilly Endowment technology grant recipients. In addition to the coordinated efforts of the four Chicago-area schools, a group of four schools in Minnesota’s Twin Cities have pooled their efforts (see related piece, “Pooled Dollars Support Multi-Faculty Training”, at the end of this article), and three schools in the Columbus, Ohio, area—Pontifical College Josephinum (Roman Catholic), Trinity Lutheran Seminary (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America), and Methodist Theological School in Ohio (United Methodist)—are also working together on Lilly-financed technological upgrading.

As McCormick and LSTC look forward together, what they see are the many important and exciting uses of information technology. Said Ralph Klein of LSTC: “When I began teaching thirty-three years ago, our students were 21-year-old men right out of college. Now that is only five percent of our student body. Half of our students are second-career seminarians, many of them women. So the question becomes, ‘How do we teach in a new climate?’ One of the arsenals in our tool box is information technology.” Klein himself did not get his first computer until halfway through his teaching career. Now he makes his students fill out an on-line questionnaire when they begin his Scripture and language courses; has his own web page (through Blackboard.com) that links students to him, each other, and the top fifty sites he finds helpful for his own teaching; and uses software that allows him to project on a screen and analyze original Hebrew and Greek texts alongside English translations.

As Klein has grown up with the technology, he has pondered its use and impact on pedagogy every step of the way. He speaks for many when he says, “Some people are resistant to the new technology, and we are sensitive to their feelings. But with the use of the internet as a tremendous resource and link to other people and to libraries, of �e-mail as a way of discussing and forming community, of web pages as a way of teaching, of CD-ROM as a way of searching biblical concordances and learning languages, it is hard to deny the positive impact of information technology on theological teaching, learning, and collaboration.”

The Lilly Endowment could not agree more. It recently allotted the first thirty recipients of the technology grants supplemental grants of $100,000 to help them continue the implementation of their plans and further their collaboration.

Pooled Dollars Support Multi-Faculty Training

by Melinda R. Heppe

“One professor raised a pencil, tapped it, and said, ‘This is as technical as I get,’” said Jim Rafferty. “Others are extremely technologically sophisticated,” he added.

Rafferty works with both types. He was hired two years ago by the Minnesota Consortium of Theological Schools—Bethel Theological Seminary (General Baptist Conference), Luther Seminary (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America), St. Paul Seminary School of Divinity at the University of St. Thomas (Roman Catholic), and United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities (United Church of Christ). His position was created to help train faculty in the use of technology not related to distance education when the four schools in Minneapolis and St. Paul decided to pool money from their separate Lilly grants for upgrading educational technology. They decided to hire one person to do the training for all of the schools and to help them cooperate with one another.

“Collaboration is the word I think about before I go to bed each night,” said Rafferty. “I think about what I’ve done that day to help the schools work together.” Nights he has gone to sleep satisfied include the one following a recent day when he spoke at a St. Paul Seminary faculty meeting and found a partner for a Luther professor doing a project on the pedagogical aspects of technology. He was pleased with a June “Computer Camp” for faculty from all four schools (“It was pretty casual, but we didn’t allow sand in the lab,” he said), and likewise pleased with a series of seminars titled “Five Interesting Things You Can Do With ...”

“In each case, those five things ranged from very simple ones that absolutely anyone could use to some that nobody there would have encountered,” he said. Rafferty’s teaching style depends on the group with which he is working. When he teaches one-on-one he is sometimes very didactic, he confesses, noting that some teachers need literal step-by-step instruction. He is can be more collaborative with teachers who have already done their homework. “At first I spent a lot of time with the techies,” Rafferty said, “but now my focus is on the second tier—those who are interested but not technologically advanced. They’ll have more influence on the rest of their peers.”

There is no career track designed to lead to a job like Rafferty’s, but he has drawn on his background in business and television in his current position. He is also theologically educated, having graduated from St. Paul Seminary. He wrote a book titled Media in Christian Formation in the early 1970s, the research for which involved watching more than 1,000 movies. (“Most of them weren’t feature length,” he quickly points out.)

Faculty from the four schools will meet in November for a day-long symposium that will feature presentations by locals on their own projects and one by a speaker who will not be on site. He will be at a Kinko’s in California, but will interact with those assembled by means of video- streaming technology. That is likely to provide yet another peaceful night for Jim Rafferty.