There are no training academies for seminary board chairs. When In Trust asked a dozen or so how they learned their roles, the inevitable answer was some version of “on the job training.”

Good board chairs learn to pull in helpful information from a variety of sources, not least of which is the reading they encounter in other areas of their lives. We asked some board chairs what they’ve read lately that has helped them in their work with their schools. Here’s what they told us.

Channeling Change

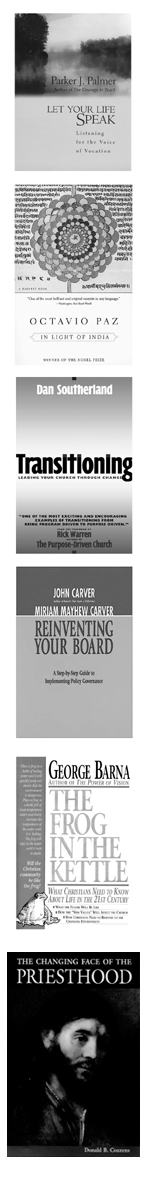

Ronald Vantine is a man who pays attention when the same message comes at him through multiple channels. He became a member of the board of United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities when a friend on the board recruited him—after another friend (who teaches at the school) had recounted stories about the seminary that intrigued him. He became chair of the board this year. So when Parker Palmer’s Let Your Life Speak: Listening for the Voice of Vocation (Jossey-Bass, $18) came up twice—first in a renewal group Vantine is a part of and then in a meditation led by the seminary’s chaplain, he took the hint. “I bought it, read it, and learned that one might do well not to be too analytical in charting one’s life course. Looking at life patterns is another approach. I’m a lawyer, so I’m pretty analytical. And it seems to me that this might be true for institutions as well as individuals.”

Ronald Vantine is a man who pays attention when the same message comes at him through multiple channels. He became a member of the board of United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities when a friend on the board recruited him—after another friend (who teaches at the school) had recounted stories about the seminary that intrigued him. He became chair of the board this year. So when Parker Palmer’s Let Your Life Speak: Listening for the Voice of Vocation (Jossey-Bass, $18) came up twice—first in a renewal group Vantine is a part of and then in a meditation led by the seminary’s chaplain, he took the hint. “I bought it, read it, and learned that one might do well not to be too analytical in charting one’s life course. Looking at life patterns is another approach. I’m a lawyer, so I’m pretty analytical. And it seems to me that this might be true for institutions as well as individuals.”

A recurring pattern in Vantine’s life is that of involvement across denominational lines. A Presbyterian, one of his favorite nonprofit board experiences was with a group called Episcopal Community Services. So it does not strike him as odd to be involved with a seminary of the United Church of Christ.

Another book he’s reading now has him peering across lines of faith. Octavio Paz’s In Light of India (Harcourt Brace, $22) was recommended by Vantine’s daughter, a grad student at the University of Chicago.

“Her interest is in Nepal,” said Vantine, “and we figure we’ll be visiting her there sooner or later. What caught me about this book, which grew out of Paz’s time as Mexico’s ambassador to India, is its treatment of the historical foundation of Hinduism and Islam. It made even me aware of the need for dialogue—I think our school has offered a course on Women and Islam, but obviously we need much more.”

Finding God’s Will

This is a time of physical transition at Winebrenner Theological Seminary. The Findlay, Ohio, school is moving back to the college campus it moved away from forty years ago. “We’ve outgrown our space,” said new board chair George Reser, “and right now we’re located on—well, it’s not exactly a thoroughfare.” But the University of Findlay—which, like the seminary, is an institution of the Churches of God, General Conference—is giving a piece of land facing a busy street, on a campus Reser calls “gorgeous.” Three-quarters of the necessary $10 million has already been raised. Groundbreaking is scheduled for next spring, and occupancy for 2004.

It is no surprise, then, that Reser has been eagerly reading a book by Dan Southerland called Transitioning (Zondervan, $18.99). “It’s a lot like The Purpose-Driven Church [by Rick Warren],” said Reser, himself a pastor and former president of his denomination, “but for churches already in existence. And the key is straightforward: find out what God wants you to do, then do it. Sometimes we don’t do that very well.”

Reser describes his training as board chair as “organic.” He’s been on the board for five years, has served on the executive committee and as vice chair. And, he says, “I’ve known the president very well for a long time.” His word to new members on boards in transition, along with the aforementioned key, is “keep rubbing shoulders. You’ll learn.”

Overhaul Happens

David Hall acknowledges that, until a couple of years ago, “our board had no particular idea of what we were supposed to be doing.” Then, by happy coincidence, at around the same time he became chair of Edmonton Baptist Seminary in Alberta, another board member started graduate study in administration. “Her insights were a big push,” said Hall, and suddenly his reading material was largely about how to overhaul the board. Their book of choice was Reinventing Your Board: A Step by Step Guide to Implementing Policy Governance by John and Miriam Mayhew Carver.

How have things changed? “There’s more authority given to the president,” said Hall, “but there is also a new set of ways to provide accountability. And, although I don’t like the word, the board does much more ‘visioning.’ And that’s helpful—people don’t feel like they’re just there to do so much rubber stamping.”

Hall thinks that the board is at the point now where they can turn their attention to other matters. And they will do so without him at the helm; he is stepping down from the chair. Hall teaches Canadian History at the University of Alberta, and although he says that his administrative experience there has helped his performance on the board, he has decided that the ten hours or so he spends each week attending to the seminary cuts too deeply into his work. “I leave the role of chair more excited about the work of the school than I was before,” he said. That probably has something to do with the board’s increased stake in the school.

Frog Lessons

“Do you know anything about frogs?” asked Tommy Hardin in a voice that’ll make you want to pull up a rocking chair and listen to his stories. He’s setting up the central image in George Barna’s The Frog in the Kettle (out of print), a book Hardin recently reread and cites as helpful to his work as chair of the committee for the M. Christopher White School of Divinity of Gardner-Webb University.

If you want to cook a live frog, apparently, you can’t just throw him into a pot of hot water—he’ll hop out. But if you start the water cool and warm it gradually, he’ll just doze off and cook. The divinity school has a history of proactivity—no sleeping through disaster for them. It was one of the first of a spate of moderate schools begun in response to the conservative takeover of Southern Baptist Convention seminaries.

Hardin didn’t set out to be the chair of a divinity school board. He attended Southern Baptist Seminary in the 1950s, but decided that his calling was to the insurance business. He became chair of the board of Gardner-Webb University in Boiling Springs, North Carolina, but was not originally excited when that school began thinking about opening a school of divinity. He’s had a turnaround, though, over the years of planning, through the start of classes in 1993, through the accreditation process, and to a current student body of 153 M.Div. students, a new D.Min. program, and plans in the works for a joint M.Div./M.B.A. He continues to sit on the board of the university, as do all ten members of the divinity school committee, and, as he puts it, “I’m involved in academic affairs and athletics—but my first love is the divinity school.”

He sits on other nonprofit boards, including that of Rutherford Hospital in Rutherfordton, North Carolina, and that role introduced him to another of his favorite pieces of reading material, Trustee magazine (www.trustee.com). The magazine is specific to trustees of hospitals, but Hardin said, “with a little adaptation, it fits right in.” He picked up the current copy from his desk and leafed through it. “Here we go—‘Adapting G.E.’s Lessons to Health Care.’ The school’s got G.E. stock; so do I for that matter. Let’s see what this is about.” Hardin continues to synthesize the things he cares about—he has arranged a meeting between the divinity school’s professor of pastoral care and the hospital administration to talk about a new chaplaincy program.

Continuing Ed

The board of Sacred Heart School of Theology, Hales Corners, Wisconsin, has an unusually lively focus on board education, and what they study often has to do with how things are being taught at the school. The board’s last retreat focused on teaching English as a second language, and how relevant that has become to their school and to others training priests. And last year, a half hour was set aside at two board meetings to discuss Donald B. Cozzens’s The Changing Face of the Priesthood: a Reflection on the Priest’s Crisis of Soul (Liturgical Press, $14.95).“A priest who is a member of the board had read it and thought it was important,” said Sister. M. Camille Kliebhan, the board’s chair. “So copies were provided to all the members. It gave us insight into what’s going on at the seminary as it helps men face their sexuality. And we had very good discussions, in part because we had a prepared list of questions. There were a variety of opinions, to be sure.”

Kliebhan is a natural at furthering board education: she taught psychology and teacher education at Cardinal Stritch College (now University) in Milwaukee before serving as the school’s president, a position from which she stepped down in 1991. “Now I’m the chancellor,” she said in a telephone interview from the university, “and I maintain an office here, but I call my current role ‘virtual retirement.’” That has freed her up for service on a number of other boards, and she does not hesitate to transfer lessons learned at one sort of institution to another. Good Stewardship: A Handbook for Seminary Trustees, edited by Barbara E. Taylor and Malcolm L. Warford (Association of Governing Boards of Colleges and Universities, $24.95; 202-296-8400) is a tool she picked up at Sacred Heart, but she explained how she used it on another board. “The president didn’t think that the board and its committees were doing enough, but he hadn’t quite gotten that he had to be a leader in that situation. I shared the book with him—heavily marked—and he was persuaded.”