There’s a myth that seminary programs are filling up with midlife career changers destined for short tenures as ordained clergy. In fact, data collected by the ATS suggests the number of younger seminarians is increasing slowly but steadily, and that debt loads and the jobs students need to hold to keep that load down may be emerging as significant challenges facing the incoming generation of students and pastors.

|

Since 1996, Dr. Francis Lonsway, director of student information resources at ATS, has been compiling data on entering and graduating students at ATS-accredited seminaries. Participation in the student questionnaire program is voluntary. Lonsway said that roughly half of ATS schools now complete surveys of graduating or entering students. Although there is significant overlap, the graduating students’ questionnaire and the entering students’ questionnaire represent different batches of schools. Comparison between aggregate demographic data from the enrollment surveys and the same data from the voluntary questionnaire suggest that the sample is representative of the landscape, he said.

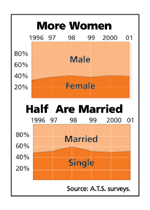

Lonsway finds the data on the age of entering students to be “very intriguing, because it goes against folklore. The folklore is that students are getting older.” However, in the schools Lonsway surveyed, the average entering student was younger in 2001 than in 1996, and the percentage of entering students under 25 increased from 28.9 percent to 33.4 percent. African Americans present a notable exception to that trend: They were not only older on average but also were disproportionately represented among students over age 50.

The Reverend Annie Kersey, a 62-year-old African-American woman, graduated in May 2002 from Alliance Theological Seminary, in Nyack, New York.

Kersey does pastoral work at Greater Centennial A.M.E.Z. Church in Mount Vernon, New York, and entered the M.Div. program after completing six years of study at Manhattan Bible Institute. She said she felt confident in her abilities as a minister but “always wanted the ultimate in education” for the “sense of accomplishment.”

Although the majority of her cohort were white evangelicals, she says that the seminary “recognized and talked about and focused on and actually taught” the sort of spirituality that she believes is sometimes labeled falsely as “emotionalism” in African-American churchgoers. She felt that the black students, most of whom were older than their white and Asian classmates, were welcomed by students and faculty. Describing herself as “grounded and established in my beliefs,” Kersey sought a conservative seminary. She was happy with Alliance, particularly with their focus on spiritual formation.

Analysis has not been done to assess the interaction between age, race, and level of educational debt, or about how those issues affect ATS schools in their attempts to recruit a more diverse student body. Lonsway believes that some seminaries are “naïve about recruiting minority students.”

Throughout the period studied, the racial makeup of students has been consistent: Seminarians at ATS schools are overwhelmingly white. Lonsway’s data suggest that 74 percent of new M.Div. students in 2001 were white.

Lonsway is concerned with the increases he’s seen in the number of students entering theological school with more than $10,000 in educational debt. (In the first five years of the study students were not asked about credit-card and other non-educational debt.) Although two-thirds of students enter with no debt, 14.8 percent entered in 2000 owing more than $15,000. And they borrow more during their graduate school years.

When she speaks of money, Kersey expresses her only disappointments with her seminary experience. She entered Alliance without debt. She chose not to work, an option made possible by her husband’s support. While she was in school, he worked and took primary responsibility for caring for their granddaughter. Still, the four-and-a-half-year seminary program required $44,000 in educational loans. She is now facing the possibility that paying off the loans may require that she take a supplemental job outside of the church.

In addition to being highly leveraged, some young students are overworked.

Like Kersey, Aaron Gray, a 26-year-old white man currently enrolled at Golden Gate Baptist Seminary’s Phoenix, Arizona, campus, is burdened with student loan debt. He and his wife Elizabeth both graduated from Southwestern Bible College. When Gray entered seminary, the couple’s joint educational debt totaled $45,000. Elizabeth planned to work while Aaron studied, but that strategy was derailed by a “surprise pregnancy with twins.” Judah Aaron and Jacob Israel were born in 2001.

Gray’s path illustrates another trend Lonsway found. About one-fifth of graduating students planned when they entered to work more than twenty hours per week, but almost two-fifths ended up doing so. Aaron has “an extensive background in security” and logs up to sixty hours per week in a Pinkerton uniform.

Both Gray and Kersey fit one of Lonsway’s most promising findings. Earlier studies suggested that “as many as 50 percent of new pastors felt unable to meet the needs of their jobs.” Some of them even reported feeling less confident after their graduate work than they felt when they began it.

Graduating students in the ATS sample reported that they felt stronger in fourteen areas of personal growth, ranging from “trust in God” to “concern for social justice,” and “self-knowledge.” They were also satisfied with the progress in their professional skills.

Only one in five students surveyed had an academic background in theology, even though many reported that they first considered religious careers while they were in college. Kersey and Gray are atypical in that they were educated at Bible colleges, and that both of them reported that their pastors had no influence in their choice of seminaries. In the majority of cases, pastors, not academic advisors, still guide the choice of schools.

What Lonsway’s data suggest is that seminaries must warn prospective students about the economic responsibilities their calling entails. Some students may need support in making difficult trade-offs, such as choosing part-time study over immersion in academic life in order to afford their loan payments.

Do you know how well resourced your incoming students are? Are most of them well versed in scripture, or should the curriculum include some “remedial” Bible courses? Will those with a call to congregational ministry be able to afford to be pastors? Successfully educating the clergy in the twenty-first century may require that seminaries take a long view of the lives of ministerial candidates, a view that begins with their undergraduate experiences and continues through their professional ministries.

Ultimately, the objective is graduates who have experiences like Kersey’s. She says her program “opened horizons, expanded the knowledge I had. I learned to think for myself instead of accepting the theology that had been handed down to me. I feel better equipped to serve God.”

Behind the Charts

The data underlying the charts that appear above were collected by Dr. Francis A. Lonsway, director of student information resources for the Association of Theological Schools in the United States and Canada, in an ongoing survey of entering students that ATS member schools participate in voluntarily. In 2001, 122 schools participated, and provided responses from 6,238 students. These charts record changes year by year among entering students who were candidates for the master of divinity degree, a candidacy that usually indicates an aspiration for professional ministry.