|

| Jerry Campbell |

On a late afternoon in July 2006, Jerry Campbell, newly arrived president of Claremont School of Theology (CST), was alone in his office. He may even have been alone in the building - one of an ensemble of stark, white modernist structures designed by Edward Durell Stone that snuggle against the base of Southern California's San Gabriel Mountains. Everyone had gone for the day, leaving the new chief in solitude to ponder how to extricate the school from a crisis.

Claremont had run up major deficits for three years, financing them by deep draws on its endowment. Enrollment was falling precipitously. Key faculty members were leaving. The school's two accrediting agencies had placed them on probation. And on Campbell's desk was a new letter from the Western Association of Schools and Colleges announcing that CST's regional accreditation would be terminated effective August 10 unless he asked for a review of the decision. The letter stated that Claremont's administration had demonstrated an inability to provide sound financial management. Moreover, it said, "the administration did not engage in honest and open communication with the accreditor" and thus lacked "institutional integrity."

Campbell recalls that he was contemplating the seriousness of this situation - indeed praying about it - when the phone rang.

"My name is Duane Dyer," said the voice. "I've got this letter from the bishop. Did you have anything to do with this letter?" He was clearly displeased.

"No," Campbell replied. "The bishop was adamant about sending it out."

"Well, I've had a good bit of experience fundraising, and I just don't think this is the way to go about it," said Dyer. "I'm a graduate of your school. I'd like to come by to talk to you about a little bit better approach to raising money."

|

| Duane Dyer |

Campbell was dubious. "Nine times out of ten when you invite somebody like that to come by, you waste another hour of your day," he says. But he agreed to see him.

Today Duane Dyer is the executive vice president for development at Claremont School of Theology. His first phone call back in 2006 was just the beginning of a solution - a turnaround that finally encompassed new board leadership and an entirely new vision for the school. In the process, Claremont has moved from death spiral to balanced budget. And Dyer has a new goal: to raise $125 million in the next three years.

Claremont School of Theology was founded as a school to prepare Methodists for ministry. Later, it was known as the intellectual home for "process theology." It was on the vanguard of launching pastoral counseling as a recognized therapeutic specialty. Today, Claremont is aiming for the cutting edge again, developing a new mission as a multireligious graduate university whose alumni of many faiths will devote themselves to repairing a fractured world.

The new vision is called the University Project. Its broad outlines are illuminated in a study document: "At the heart of religious and spiritual traditions lie such values as compassion and a commitment to the flourishing of all life," it reads. "Too often, however, religious practitioners have lost their way and fail to live true to the values of their own traditions. Yet, at their best, religious communities can be the inspiration for movements toward peace, justice and reconciliation with the world's conflicts."

President Jerry Campbell is one of the chief architects of CST's new vision. A high-energy United Methodist minister and academic librarian who assumed the mantle of presidency at 61, he jokes that his position is an "after-retirement job." But Campbell is surrounded by a group of trustees, teachers, and administrators - some recruited by him, others long associated with the school - who have become a smoothly functioning, creative, and hopeful team.

|

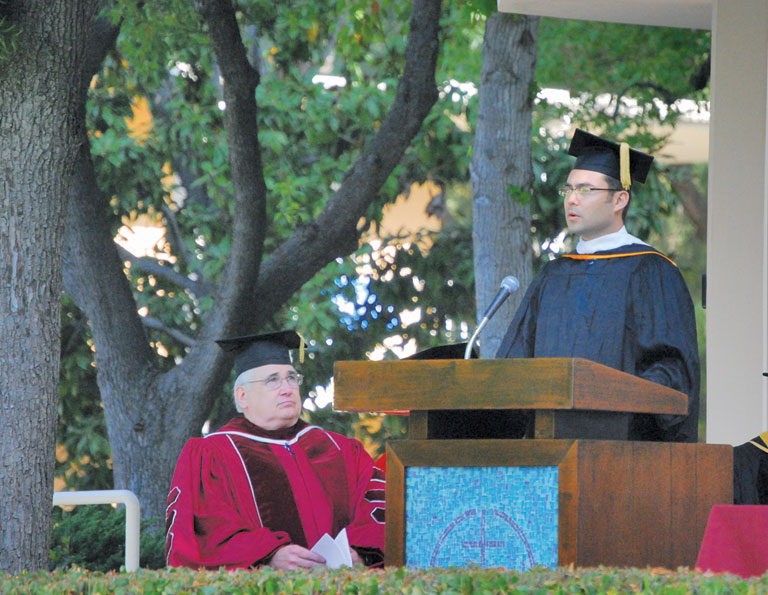

Imam Jihad Turk, director of religious affairs at the Islamic Center of Southern California, offers a prayer at Claremont School of Theology’s 2009 commencement. At left sits President Jerry Campbell.

(Photo courtesy of CST)

|

Making needed changes

Campbell's first step as president was to address the threat of losing regional accreditation, so he filed a formal request that the Western Association of Schools and Colleges review its decision, explaining that a new president and a new dean, Susan Nelson, were in place. The agency agreed to a review.

Meanwhile, he launched the painful process of balancing the 2006-07 budget. By year's end, when he and a new financial team closed the books, the school had spent $7,990,673 on program, administration, and fund-raising, an 8.5 percent reduction from the year before. Administration took the biggest hit, dropping 22 percent to $1,386,969. Fundraising was next, with a 14 percent cut to $478,822. The reduction in the academic program was relatively modest, ending the year at $6,124,882 after a 4 percent cut. In the retrenchment, six administrative jobs were eliminated and 2.5 faculty positions were left unfilled. The draw on the endowment, which had been 6.25 percent in 2005 and 5.88 percent in 2006, was reduced to 5.42 percent.

Changes in governance accompanied the cost-cutting. When Campbell was named president, he agreed that new board leadership was essential. He soon invited Sandra Bane to the board of trustees. A retired partner of accounting giant KPMG, Bane was a fellow member of Campbell's congregation, First United Methodist in Pasadena. Bane declined, pleading an overly full plate. She already served on three corporate boards and traveled extensively. She shared a second home on the East Coast with her husband, Dan Bane, chairman and chief executive of the Trader Joe's grocery chain. Rarely at home in Pasadena more than one week a month, she nevertheless served on leadership bodies both in her own congregation and in the California-Pacific Annual Conference of the United Methodist Church. She felt overtaxed and unmotivated.

But Campbell can be persuasive. He told Bane about the problems with the school's financial management. He recounted the demands for reform made by the regional accrediting agency and by the Association of Theological Schools. Bane agreed that Claremont could use her help. She also began to see the up side of the new role. "I was struggling with my next course in my own faith journey at that point," she says. She knew that God had given her some gifts. "I had to give back."

|

Sandra Bane at a trustee meeting in 2009

(Photo courtesy of CST)

|

In September 2006, Sandra Bane was elected chair of the board of CST. In November, the Western Association of Colleges and Schools rescinded its decision to disaccredit immediately and substituted a show-cause order, allowing one year for the school to demonstrate why accreditation should not be revoked.

Restructuring the administration and finances in order to hang on to accreditation was a formidable task. Gamward Quan, associate vice president for financial affairs and planning, said he sometimes seemed to be working 24 hours a day on the task, which concluded with the delivery of a 450-page report to the accrediting agency in November 2008.

For John Dickason, the school's director of libraries and technologies since 2001, who was also named chief accreditation officer, the effort represented a refreshing new wind. "The student decline at CST was more serious than at the other United Methodist schools or mainline schools in general," he said. "We had to fix this or we would die. Finally we had someone at the helm who realized that."

Indeed, the enrollment decline has been ominous (see table on previous page). Not surprisingly, tuition income declined in parallel, falling from $2.4 million in the 2005-06 academic year to $2.0 million in 2008-09. This autumn, 229 students are enrolled.

As Dickason wrestled with accreditation issues, it became clear to him, as it did to others, that the challenge was more than simply economizing or marketing. Rather, Claremont School of Theology needed new educational goals, a new mission, perhaps a new identity. The status quo was actually more risky than change.

In the midst of this ferment, the idea of an interreligious university began to emerge. A new university would build on CST's strengths but take them further. It would de-emphasize denominationalism in favor of interfaith cooperation. It would educate students to contribute to public dialogue from a variety of ethical and religious perspectives. "It was an astonishing idea - crazy," says Dickason. "But I couldn't think of anything else that would turn the school around."

New board chair Sandra Bane came to a similar conclusion, and together, board, administration, and faculty began to work to bring the new university into being.

A new graduate division within CST

One of the first fruits of their labor is a provisionally named School of Ethics, Politics, and Society, which is projected to open in Autumn 2010 as the first new unit of the interfaith university. "Particular areas of focus in the school will include peace studies, sustainability, social justice, and grassroots organizing," says an initial prospectus. Awarding M.A. and Ph.D. degrees in religion, the new academic division "will prepare academic and professional leaders for work in a variety of contexts including national and international nonprofit educational, governmental, and advocacy organizations."

Five faculty members will form the instructional core, says Campbell - three current CST professors and two that will be recruited. Richard Amesbury, a CST faculty member whose research examines the intersection of ethics, political theory, and religious philosophy, is drawing up the school's preliminary design.

Duane Dyer, the development chief, says that funding is mostly in place, anchored by a $5 million gift from an anonymous donor who is close to the school and has been an important voice in discussions about Claremont's new direction. The $125 million that Dyer still plans to raise is a large sum by the standards of most North American graduate theological schools, but Dyer is quick to emphasize the new mission. "We're not a theological school," he says. Rather, the school's mission has already moved beyond theological studies, and the money to bring into being a new interreligious university can be raised, he feels. Dyer is confident that CST's new direction will capture the interest not only of traditional church-related philanthropists, but also of Jewish, Muslim, and possibly Hindu givers.

Backward or forward?

One recent afternoon, Jerry Campbell and dean Susan Nelson were reflecting on the transformations at Claremont School of Theology over the last three years. "You know, I got advice that the only way we could effectively cope with this circumstance we were in was to become more Methodist," Campbell recalled. "Go back to our roots, stick with Father Wesley. And I have seen schools do that."

He paused. "But just to hunker down in spite of the numbers and to fight with our sister schools for a larger share of a shrinking pie seemed like bad advice." (That said, there's no plan for CST to separate from the United Methodist Church or to forego funding from the church's Board of Higher Education and Ministry.)

How did the faculty and board come to embrace the new vision for a multifaith university? "I think it is somewhat true in a certain language that the Spirit came upon us," he said, choosing careful words but confident in CST's new direction. "I have never seen another theology faculty united around an effort - and consistently united now for three years - and doing things we didn't think we were capable of."

He recalled that in the Hebrew Bible, God told Abraham that he wouldn't live to see the fulfillment of the divine promise, but Abraham nevertheless had God's assurance that he could die in peace.

"What this means to me," Campbell said, "is I don't really have to be concerned whether it works or not. That's too long-term an issue for me to worry over." He just wants to get started.

The long view

A few blocks away from the campus, the Rev. F. Thomas Trotter lives in an attractive retirement condominium. Now 83, Trotter served 11 years as dean of Claremont School of Theology. Later he was president of what is now Alaska Pacific University and then served 14 years as general secretary of the United Methodist Church's Board of Higher Education and Ministry. He has been a trustee of Claremont School of Theology for many years.

Trotter chaired the search committee that recruited Jerry Campbell to CST. He also helped recruit Campbell's two immediate predecessors. Robert Edgar, a United Methodist minister and six-term member of Congress, was the school's president from 1990 to 2000, when he left to become general secretary of the National Council of Churches. Edgar was succeeded by Philip A. Amerson, who departed in 2006 to become president of Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary.

Trotter acknowledges that when Campbell was hired, Claremont was facing a crisis, but Trotter is now enthused about its future. He is fully supportive of the move toward a multifaith university. "The school is not going to just survive," he said, "It's going to thrive."

It's going to thrive not by returning to its Methodist roots, but by spreading its arms, he argues. "The confessional seminary is a dead duck."

With a continuing unified effort by the board and the faculty - as well as some backers with deep pockets and generous hearts - Claremont School of Theology may well thrive as a new kind of multifaith school. They've determined the destination. They've begun the journey.

Board members embrace a multifaith future

|

Graduates at commencement 2009

(Photo courtesy of CST)

|

Ten members of CST's 29 current trustees (not counting faculty and student representatives) are new in the last three years. Rabbi Gary Greenebaum is one, having joined eight months ago. The U.S. director of interreligious affairs for the American Jewish Committee, he said he was intrigued by Claremont's effort to explore religious pluralism as something more than simply tolerance.

"By sharing the campus, everyone grows," Greenebaum says. "Diana Eck says you can't understand your own religion until you understand others," he adds, citing a professor of comparative religion at Harvard. Applying that principle to himself, he agreed to join the board after visiting a class on the theology of John Wesley, the founder of Methodism.

Two United Methodist members of the board are also optimistic about the school's future. Earl Butler, a retired insurance executive who is a lay leader in his Southern California congregation, says he is intrigued that the student body includes Jews and Muslims as well as a wide variety of Christians. He sees their presence as the fruition of the work of the team that Jerry Campbell created when he became president of the school - a team that included trustees, faculty, and staff. "We are looking to the needs of the outside world," he says.

The Rev. Tonya S. Harris also sees the school moving in the right direction. A 2003 graduate of Claremont, she is pastor of a United Methodist church in Lynwood, California, a blue-collar suburb of Los Angeles. Her neighborhood has shifted from white to black to Latino, and she's trying to build a multicultural worshiping community with a variety of community-focused services, including a food ministry, literacy coaching, and antigang programs. "I believe that a seminary education is preparation not only for service in the church but also for service in the world," she says. "Since the introduction of the university, the school has been right on the spot of what the world is beginning to dialogue about."