WHEN BRIAN STELCK helped pilot an online spiritual formation course at Carey Theological College, the outcome surprised even him. “The safety of the Internet seems to draw out students who might otherwise be silent,” says Stelck, who is president of the Baptist institution in Vancouver. As an example, he recalls a young Chinese woman who took an online course with him. In a traditional classroom setting, she probably would not have contributed to a discussion until everyone older and more experienced had spoken, but online, she learned to know and trust her classmates. “When they met online using Wimba for a live session, she soon was taking on a 60-year-old Lutheran pastor!” Stelck says.

“That would never have happened in a face-to-face setting. In an Ephesians 2 sense, barriers that divide people were breaking down.”

Stelck’s anecdote hints at one of the most pressing issues in online theological education: the place of spiritual formation in the online classroom, or the place of the online classroom in spiritual formation. After years of experience and rigorous third-party evaluation, educators know that students can learn online. But is the distance-learning environment conducive to instilling the formative aspects of ministry preparation?

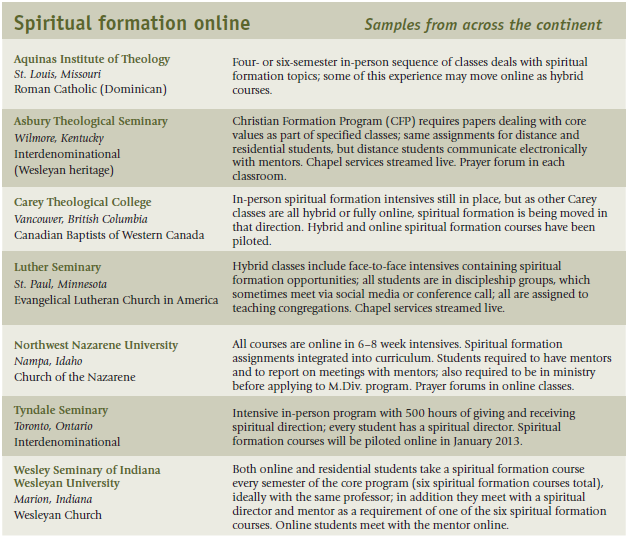

To help answer this question, we interviewed leaders at several schools that offer (or plan to offer) a spiritual formation component as part of their online curriculum.

Not surprisingly, spiritual formation varies widely by denomination and geographical location, but some of the programs share certain characteristics. Here’s what we have been learning:

1. Intensive and hybrid formats, along with local mentoring programs, augment the spiritual formation of online students.

Luther Seminary, St. Paul, Minnesota. Online students at Luther are divided into cohorts, attend online classes together with their assigned group, and often develop other ways of communicating, such as creating groups and posting updates on Facebook.

Many meet once a week in discipleship groups via conference call, and all gather in person for two-week intensives twice a year. Joy Aarsvold, coordinator for the M.Div. distance learning program, describes these intensive sessions as “not only academically rigorous times, but spiritually nourishing times” — complete with vibrant worship.

While every Luther student, whether online or residential, is attached to a “teaching congregation,” online students spend extra time each week with mentor pastors at their home churches. Aarsvold has noticed that online students seem to show a higher degree of commitment to this work than some residential students, who are usually assigned randomly to a church in the Minneapolis–St. Paul area.

Carey Theological College, Vancouver, British Columbia. Carey offers two-thirds of its classes totally online and one-third as hybrids. President Brian Stelck believes that faculty can teach counseling and instill spiritual direction as effectively online as in person. In fact, Carey’s eight-day spiritual formation intensives are being reconfigured to reflect the hybrid model — part of the intensive will be online, part in person.

Wesley Seminary at Indiana Wesleyan University, Marion, Indiana. Seminarians at this Wesleyan Church institution begin their academic program in a face-to-face intensive and return to campus once a year for two weeks. Dean Ken Schenck explains that “one goal of the annual August ‘reunions’ is that they take on the character of a ministers’ conference and retreat.”

Northwest Nazarene University, Nampa, Idaho. This Church of the Nazarene school conducts its M.A. and M.Div. programs totally online, which its regional accrediting agency permits (although the Association of Theological Schools Commission on Accrediting does not). Mark Maddix, professor of practical theology and dean of the School of Theology and Christian Ministries, reports that students meet with mentors on a regular basis to complete required assignments and reports. Most students live close to their mentors and, as at Luther, mentors typically are pastors or staff members at local churches. This helps students contextualize their education. (Northwest Nazarene also requires M.Div. students to be engaged in ministry before applying to the program.)

Northwest Nazarene and Luther operate with similar assumptions about distance students and spiritual formation, and other schools, even those in the early stages of designing online curriculum, are also embracing this model. Michael DeLashmutt, Luther’s associate dean for first theological degrees at Luther, says, “Because distance learning students are embedded in a ministry context, their ongoing theological reflection on the practice of ministry is part of their spiritual and vocational formation.” He thinks this makes distance learning an especially powerful vehicle for spiritual formation, as it involves developing skills under the supervision of a mentor in a teaching congregation.

Tyndale University College and Seminary, Toronto, Ontario. Tyndale, a nondenominational, evangelical institution with undergraduate and graduate programs, has an intensive in-person focus on spiritual formation and is beginning to take its program online. David Sherbino, professor of spirituality and pastoral ministry, says they plan to tap an extensive network of existing spiritual directors both face to face and through conferencing software. They also plan to bring students to campus for three-day retreats.

Aquinas Institute of Theology, St. Louis, Missouri. Marian Love, director of lay spiritual formation and adjunct instructor in pastoral theology, is in charge of creating an online version of this Catholic school’s comprehensive formation sequence for lay ministers. Despite her own misgivings about online formation, she intends to include an intensive retreat time in each semester of the new online sequence. Some of Aquinas’s current hybrid courses meet once a semester for intensives, but once a semester is probably insufficient for spiritual formation classes, she says.

2. Video-conferencing capability and the use of social media are useful for some schools, but other campuses prefer more familiar technology.

Schools vary in how they use technology and social media to facilitate formation. Some question its usefulness at all. Love, for example, does not feel that Skype and conferencing software give her the same sense of presence she receives in person. “Would we want our priests formed totally online?” she wonders — and then concludes that lack of face-to-face contact would be troublesome. “There would be limited opportunity to observe the way they interact with others,” she says, and an inability to evaluate pastoral skills.

Love adds that lay ministers shouldn’t be formed completely online either. “These venues give you some buffer,” she adds. “You don’t see everything about the person.”

But other schools have been quick to experiment with conferencing software and Facebook. Carey Theological College has used Wimba in recent online classes, including a core spiritual formation class.

Wimba also is available to professors at Asbury Theological Seminary, though using the virtual classroom program is not required in any particular course. Northwest Nazarene uses Adobe Connect extensively for “live” meetings and employs short video and audio clips in classes (but the clips are not too long — Maddix says they try to avoid having too many talking heads).

While no seminary officially requires Skype, several report that students and faculty use it either as an adjunct to the online classroom or for more informal get-togethers. At Asbury and Tyndale, students use Skype to meet with their mentors. Also, while no schools report requiring Facebook or Google Plus groups for their online cohorts, several point out that these groups frequently form on their own. Nearly every school we spoke to streams chapel services live.

Indiana Wesleyan and Asbury also report students posting YouTube videos to interact with each other visually.

Older technology definitely is not dead. Luther, for example, makes extensive use of conference calls, according to Aarsvold, though she admits they feel “antiquated and cumbersome.” (Many administrators agreed that the conversation about videoconferencing software will be different in a few years when more bugs are worked out.) Asbury students frequently meet with mentors by telephone as well as by Skype.

3. Geography is a key factor in how a school views the necessity for online classes in general and online spiritual formation in particular.

“Folks are so far apart,” says Stelck, president of Carey Theological College. When your seminary is in western Canada, as Stelck’s is, just assembling a professor and students for a course is difficult and expensive — in some cases, airfare exceeds the course tuition. To solve the dilemma, Carey has been experimenting with online retreats. Faculty members identify readings for discussion, meditation, or lectio divina. Students and instructors then gather online to interact with the readings. The school also has tried online guided silent retreats after which students reflect on the experience of spending a weekend in silence.

Stelck emphasizes the ability to expand the geographical area touched by Carey through online courses: “Our constituency is so spread out geographically that this technology is opening learning opportunities for people who would never have considered formal education because of their circumstances.”

The geographical reach of a school also plays into the demand for online courses, formational or otherwise. At Tyndale, Professor David Sherbino reports that the school has students all over the world enrolled in courses. Next year, he and six students will travel to India to staff a retreat that has the potential to stimulate a greater demand for courses.

|

At Northwest Nazarene University, exit interviews show that students' personal and spiritual formation has grown since the online program began, says Dean Mark Maddix.

Courtesy Steve Paul/Northwest Nazarene University |

4. Schools are attempting to integrate online and face-to-face students into the same formation programs.

Theological schools are united in their desire to offer residential and distance students the same formational experiences. Streaming chapel services is an obvious way to accomplish this, but not the only way. Luther divides its entire seminary into “opt-in” discipleship groups, and Aarsvold the coordinator of the distance learning program, finds that online students seem more committed to this experience, which frequently takes place through phone or Facebook meetings.

Asbury has a Christian Formation Plan that assigns papers and assessments dealing with six core values and then requires discussions with a faculty guide. According to Steve Stratton, professor of counseling and pastoral care at Asbury, the only difference between distance and residential students is the technological manner of the conversations with their guide.

Indiana Wesleyan follows a similar plan, according to Dean Schenck: “Students here take a spiritual formation course every semester of the core program — six courses alongside the six core praxis courses,” he says. “We try to keep them with the same professor, making this person a mentor to them throughout the program. In addition, they meet with a spiritual director and a mentor for one of the spiritual formation courses.” Online cohorts do this online and residential cohorts do it on site, but no other differences exist between the programs.

Northwest Nazarene requires all students to have mentors and all classes to contain a spiritual formation component. Similarly, each student at Tyndale must have a spiritual director, and Sherbino does not see this changing as the spiritual formation piece of the program moves online. And at Indiana Wesleyan, Schenck says that the program “is exactly the same both on campus and online, and the response is identical.”

What does vary among schools is how the spiritual formation program, in its online and face-to-face manifestations, is integrated into the curriculum. Some schools, while recognizing that formation occurs throughout the seminary experience, include clearly defined sets of experiences and courses. Luther, Tyndale, and Aquinas have taken this approach. Aquinas, which is run by the Dominican religious order, requires its lay ministry students to take a four or six-semester sequence (four for M.A., six for M.Div.) that progressively moves through issues of devotional and psychological formation.

Other seminaries, while offering specific courses in spiritual formation, emphasize the integration of formation into all aspects of academic coursework. Asbury and Northwest Nazarene embed spiritual formation assignments in certain courses—Northwest Nazarene requires some sort of formational component in every class — and both place emphasis on having, and using, prayer forums in all classes.

“We expect all faculty members to have a spiritual presence in the classroom,” says Dale Hale, director of distributed learning at Asbury. He adds that on his wish list is that every faculty member would “take the role of spiritual mentor seriously, to look beyond the actual lesson and see ways to apply [it] to spiritual growth of individuals.”

|

| Spiritual formation is an integral part of the classroom at Asbury Theological Seminary, both for residential students and for those who are taking courses online. |

5. A number of schools report the formation of a deep spiritual community among distance learners.

According to Dean Michael DeLashmutt, Luther experimented for several years with a number of approaches to content delivery. In resulting surveys, about 50 to 60 percent of residential students and 40 percent of online-only students had a sense of a community of learning, but 90 percent reported developing such a community through a combination of intensives and online study. Aarsvold says that distance students display “an incredible sense of belonging to the community” and express ownership of place when they come on campus. “In some ways, it’s amazing to see how our distributed learners seek to incorporate residential students into their lives together.” Anecdotally, other seminary administrators back this up. Schenck at Indiana Wesleyan thinks that the intensive retreat portion of classes means that students develop very close relationships with one another, even though they are apart most of the year.

Administrators also testify to a bond formed through the online experience. Janet Clark, senior academic vice president at Tyndale, notes that Tyndale has found “a depth of community is often formed among online learners, particularly when they are divided into small groups for in-depth reflection and discussion.” Clark says that the bonds among online students sometimes extend beyond official discussion forums to sidebar discussions, where they meet and pray outside of their official classroom setting, and sometimes after the course ends. At Asbury, Hale reports similar experiences in his online classes — students rallying around their classmates in prayer and support when they face troubles. At Northwest Nazarene, Maddix says that exit interviews show that personal and spiritual formation is increased as a result of the university’s online program.

Remembering the pilot course he taught at Carey, President Stelck describes the “assignments, the reflection, and the interaction” as significant; another faculty member involved with the same course stated that the “depth of reflection and personal insight” surprised him. Carey’s early indication, according to Stelck, is that class interaction “exceeds that which is experienced in most on-campus term courses.”

Administrators’ wish list

What could improve spiritual formation for online students? In Trust asked several administrators to respond. Here’s what they said:

- The ability to add face-to-face courses in distant geographical areas wherever a significant enough number of students makes this feasible, and have this count toward ATS residency requirements.

- More sophisticated video software and ways to use video interactivity in courses; more technological support for streaming chapel services.

- Greater ability for students to access courses on mobile devices.

- Better ways to support the relationship of mentoring pastors with distance students.

- More commitment of faculty to spiritual formation leadership and engagement.

- Expanded offerings of online courses to increase accessibility to laity, nontraditional students, and those at a geographical distance.

- Trained spiritual directors for those schools that do not already have them, for both distance and residential students.

Questions for boards about online formation

Expertise

- Do you have access to an educational technology expert — someone who can address the board’s questions without being a partisan for one particular vendor or mode of technology?

- In what ways can your board learn about spirituality and educational technology from other schools within your denomination or geographic region?

Budget

- If your school is launching into new forms of online learning, or if you have new expectations for spiritual or vocational formation, how are you setting the startup budget?

- How do you know if you are being realistic about the costs and potential income from online learning?

- Have you compared your budget in this area with the budgets of peer institutions?

Fundraising

- How may online education provide new fundraising opportunities?

- If you have well-established online programs, ask the development officer for data on giving from former online students.

- Do you have graduates or friends in the tech industry who might sponsor pilot programs that emphasize spiritual formation?

Enrollment management

- How realistic are your projections for future online enrollment? Do you anticipate that online students will expect more or less financial aid?

- Do you expect that a greater focus on comprehensive online formation and education will affect your student demographics — drawing, for example, more (or fewer) younger students, ethnic minority students, or international students?

Faculty

- How are faculty compensated for the additional time required to develop new online courses or new expertise in spiritual or human formation?

- Has the board heard from the academic dean and faculty about educational and spiritual outcomes from online education?

Strategic direction and planning

- How is the board grappling with the reality that educational technology changes rapidly? Is the school tied to a particular form of delivery just when the technology is moving in a new direction?

- Realizing that educational technology will be different in just a few years, how can the board retain its flexibility while offering strategic direction to the administration?