For more than half a century, Union Theological Seminary in Virginia and The Presbyterian School of Christian Education sat comfortably across from each other on Brook Road in Richmond. Both were flagship institutions of the Southern branch of the Presbyterian Church — one school serving primarily women, the other mostly men. They shared faculty, resources, and dual-degree programs. Their history was long and their missions distinct but compatible.

|

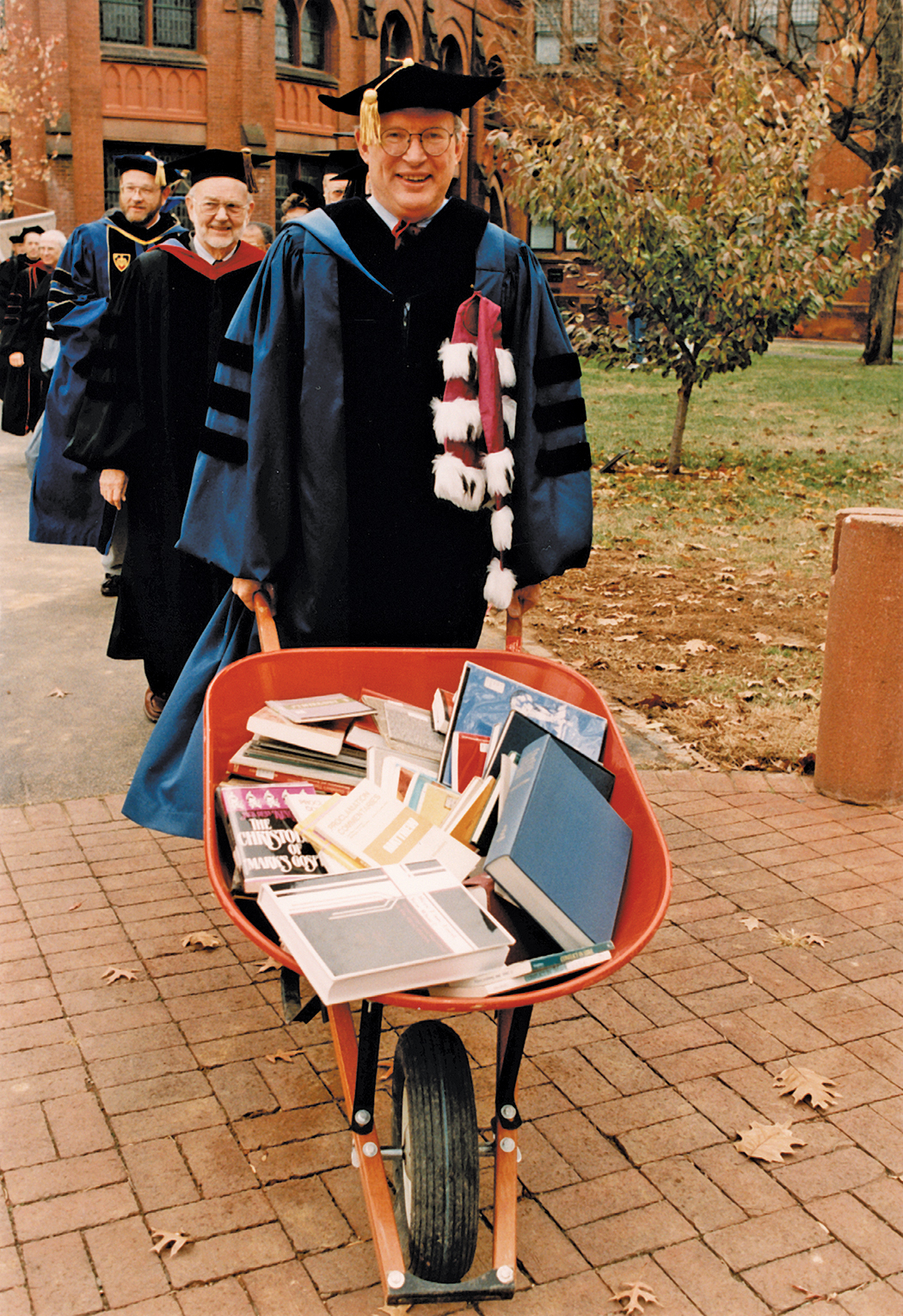

Louis Weeks leads a procession of faculty in 1996 to commemorate the opening of Union Theological Seminary's William Smith Morton Library.

Credit: Union Presbyterian Seminary |

The Presbyterian School of Christian Education (PSCE), founded in 1914 as the General Assembly’s Training School for Lay Workers, was, by the 1990s, the last of its breed — an institution wholly dedicated to scholarship and training in Christian education, a field dominated by women. Students at PSCE were not, for the most part, preparing for ordination. Rather, they were preparing to become directors of Christian education, a vocation prized in the church but not highly paid in local congregations. Graduates of PSCE were not capable of making big donations to their alma mater. The faculty was paid less than their colleagues at the seminary across Brook Road, and the school had fewer than 100 FTE students.

PSCE’s finances were precarious, in part, because of its history of church support. Until 1959, it had been an agency of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS) and had been forbidden from raising its own funds. Even after it gained its independence, PSCE continued to receive church support. But when the Atlanta-based PCUS and the New York-based United Presbyterian Church (UPC) merged in 1983 to form the Presbyterian Church (USA), church funding dried up, and PSCE had few reserves.

In 1992, when Wayne Boulton arrived as the new president, PSCE’s financial outlook was as bleak as its alumnae were loyal. The school had far more space than needed — a whole campus of underused buildings — and once Boulton and a new financial officer started crunching the numbers, they could tell that the institution had become financially unsustainable, spending 13 percent of its $3 million endowment each year. But most of those around Boulton wanted to look on the bright side — closing was unthinkable. There were calls for increased fundraising and even a capital campaign.

Boulton realized that he needed to sell the school’s largest building, Watts Hall. Doing so would accomplish two purposes: It would get all constituents of the school—board, faculty, graduates, and Presbyterians at large — to see the gravity of their financial trouble. And in so doing, it would actually improve PSCE’s financial situation.

The opposition came quickly. A group of former students aligned themselves with popular faculty members and started a monthly newsletter to oppose the sale. Boulton himself describes it as a battle — one that pro-sale forces won in a narrow three-vote margin by the trustees in 1995.

After the sale of Watts Hall went through, the financial situation at PSCE was at once slightly more manageable and greatly more visible. With money in the bank, Boulton could turn to the prospect of consolidation from a position of greater strength. He believed that PSCE required further change, so he and his executive staff turned to their larger and completely familiar Presbyterian neighbor.

In the 1990s, Union Theological Seminary had more financial stability than PSCE. Its endowment was a respectable $55 million, though it was drawing about 7 percent a year. The seminary’s fundraising potential was stronger than its neighbor’s — the Union faculty was known for rigorous scholarship in traditional disciplines, like systematic theology, that were based heavily on biblical languages; many of its graduates went on to become pastors of tall-steeple churches.

Louis Weeks was the president of Union at the time. He took the reins in 1994, and the federation with the PSCE was one of the first challenges that arose in his tenure. Early on, he and Boulton contracted with three consultants to guide them: Ellis Nelson, Laura Lewis, and Anthony Ruger. Lewis was the first Ed.D. graduate from PSCE, and the others had solid reputations in Presbyterian circles. The consultants spoke with the officials from Union and PSCE and then drafted a plan for federation.

The work of the consultants, funded by grants, played an important role throughout the process — from engaging the support of key constituencies to navigating the paperwork required to maintain the new institution’s accreditation. They were also important for maintaining a sense that the process was proceeding fairly — specifically, that PSCE wasn’t going to disappear. As at many schools going through this process, language was very important. A merger didn’t sit well with the participants; neither did marriage. So they settled on federation.

“I learned very quickly that I couldn't speak publicly about the federation because I was identified with the prosperous side,” Weeks says. “I let the consultants carry most of the public communication on it and particularly to the PSCE alums, who were the major group who did not want this merger to occur. They knew their school was unique, and they didn't want it to die.”

The concern that the PSCE would be swallowed up by the seminary and lose its identity was legitimate. Union was undeniably negotiating from a stronger position. One way the participants worked to address this concern and work toward balance was to give deference to PSCE throughout the process.

“We synchronized the board meeting, so that the PSCE people voted first, and then the Union people voted second,” Weeks says. “That was typical of the way we weighted the discussion and the actions. We kept letting the weaker institution have equal time or sometimes even have more say in some things that went on than the stronger institution.”

Concerns about institutional identity also arose when it came time to decide on a name for the new school. Laura Lewis helped come up with the new institution’s name, Union Theological Seminary and Presbyterian School of Christian Education (Union-PSCE).

“Each part of the name lost something in that process,” Weeks says. “Union lost ‘in Virginia,’ and the School of Christian Education lost the definite article. It was no longer the school. There was improvement in the identity of both.”

|

The former campus of The Presbyterian School of Christian Education is now home to Veritas School, a Christian K-12 school with almost 500 students.

Credit: Veritas School |

One tool that guided Weeks through his role in the process was Leadership Without Easy Answers by Ronald Heifetz. Weeks credits the book with showing him the importance of “getting on the balcony” in preparation for the transition — and he’s continued to use it in his work as a consultant for seminaries considering mergers or new campuses. Weeks later shared the book with his executive staff and some of his board members. Part of Heifetz’s leadership philosophy includes giving the work back to the people. This turned out to be an important piece of getting the faculty from the two schools involved and working together.

“We got the faculty to work on issues related to the faculty,” Weeks says. “They didn’t come out with the answers that I would have liked for them to come out with. But their answers were not as significant as the fact they were working together.”

The newly consolidated institution was soon working on a strategic plan that included planting a campus in Charlotte, North Carolina.

“At Charlotte we decided to offer the M.Div. and the master of arts in Christian education. Had we not been merged, I doubt if we would have initially offered the Christian education degree in Charlotte,” Weeks says. “I honestly think that our new identity strengthened the Charlotte campus and continues to strengthen it.”

|

Left: The former campus of The Presbyterian School of Christian Education in Richmond, Virginia. Right: Union Presbyterian Seminary.

Credit: Google Earth |

The federation of the two schools had a positive effect on the financial outlook of Union-PSCE. By the time of Weeks’s retirement in 2007, Union-PSCE had 400 students and an endowment of $120 million, a considerable increase in both the school’s financial stability and its ability to meet its expanded mission.

What of PSCE — did it lose its institutional identity in the end? After all, another name change just a few years ago changed Union-PSCE into Union Presbyterian Seminary, with no mention of Christian education.

Wayne Boulton, the former PSCE president, thinks that his old school’s mission does survive and is personified in its president, Brian Blount, who has led the school since 2007. “Blount is a fantastic church leader and New Testament scholar,” he says. “He comes with a heart for Christian education that aligns perfectly with the tradition of PSCE.” Boulton is convinced that Christian education remains a unique strength of the seminary.

“We were afraid that the special genius of Christian education as ministry would be lost within a larger school. And it really took 20 years for the integration to get done,” says Boulton, who departed as part of the federation agreement and returned to pastoral ministry. “I’m not saying that everything is perfect now. But looking back, this was the way to go.”