A piano teacher sitting beside a student: That’s the image Larry Braskamp uses to describe the appropriate posture and attitude for useful assessment of academic presidents, including those who lead seminaries.

Sitting Beside — Braskamp’s title for a new, free guide to presidential assessment — is a different relationship than sitting in judgment, he says, noting that it emphasizes the developmental nature of assessment, as opposed to the more prosecutorial stance of “standing over.” When sitting beside, both parties are on the same level.

It’s an approach Braskamp has nurtured during his five decades of studying and practicing assessment. He’s been an administrator at several institutions, including Loyola University Chicago (a Catholic school) and Elmhurst College (affiliated with the United Church of Christ), and he’s the former director of the Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA).

“We’re trying to help people improve, not prove anything,” says Braskamp. “The ultimate purpose of the assessment described in the guide is to fulfill the board’s goal of enhancing the institution’s well-being by helping the president become an even more effective leader.”

|

Nov. 15 webinar on presidential assessment

To learn more about the “sitting beside” approach to presidential assessment, join the In Trust Center’s November 15 webinar, Sitting Beside Rather than Standing Over: A Guide to Presidential Assessment. A copy of the guide will be sent to each registrant ahead of time. Braskamp will explain how to use the guide during the webinar.

More information: www.intrust.org/webinars.

|

Historically, boards have not prioritized presidential assessment, he notes, with informal “you’re doing a good job” evaluations being the norm until the last decade. Yet even formal assessments tend to be one-way communications that don’t emphasize helping institutions solve problems and achieve their missions. Instead, they tend to focus on the president’s administrative style.

Braskamp believes presidents — especially newer and younger ones — want feedback, and presidential assessment is definitely part of the board’s fiduciary responsibility. “The board owns the assessment process,” he says. “It may be a subgroup, executive committee, or an ad hoc group that actually carries out assessment, but everyone should have ownership and want to help the president become better.”

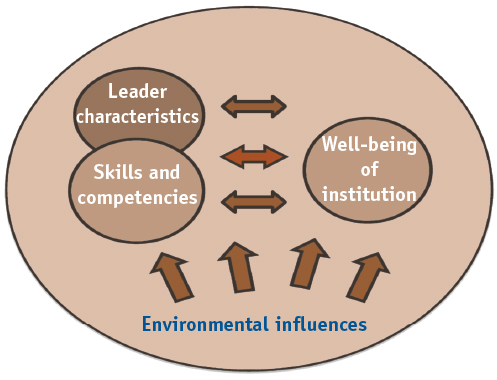

Assessing only a president’s leadership style — including their popularity, personality, or even skills — is incomplete, the guide explains. Presidential assessment must also evaluate how well the school is balancing its budget, meeting enrollment goals, serving the denomination, and meeting the needs of society.

The 34-page guide includes instructions on every step of the process: selecting a task force, determining assessment criteria, collecting and interpreting evidence, providing useful feedback to the president, and informing other stakeholders of the assessment. Confidentiality, staffing, and timing are also covered, with Braskamp recommending an annual presidential assessment as well as comprehensive assessments every three to five years.

Three appendices list about 150 possible assessment criteria based on the guide’s three categories: (1) personal characteristics, (2) skills and competencies, and (3) performance of responsibilities. Board members can use this “cafeteria menu” to select the criteria most pertinent to their institution. The process described in the guide can also be useful for boards that are looking for a new president.

Braskamp says the approach is nonthreatening, with a positive view of change and development. Yet he doesn’t deny the tension between developmental and evaluative assessment. While the process described in the guide is meant to foster improvement and problem solving, he recognizes that sometimes assessment is used to make decisions about a president’s future status, including salary adjustments. He advises that the two processes be distinct.

|

|

The current successes of a president are a good barometer of future success, but not a guarantee, writes Larry Braskamp in Sitting Beside. If the environmental forces are changing or the goals of the institution need to change in order to remain competitive, then the demands and expectations on the president may also change. A comprehensive presidential assessment takes all these into account.

From Sitting Beside |

Braskamp’s guide can help boards create two-way, collaborative assessment processes, which ease some of the anxiety of being evaluated, while still holding presidents accountable. “The focus is on growth and change, not on being judgmental or personal,” Braskamp says, citing the work of Stanford psychologist Carol S. Dweck on the “growth mindset,” which has been used effectively in companies such as Amazon, in professional coaching, and even in elementary education.

The “sitting beside” concept is natural for a religious organization, Braskamp believes. “People of religious faith already look at the integrity and well-being of a person,” he says. “There is a real respect for the individual, since most religious faiths see that everybody is a child of God.”

If anything, religious organizations may tend to forget to emphasize the health of the institution. “Sometimes the president is a good person but not effective for that institution at that particular time or in the future. With assessment, we look at the institution where it currently is, and where it needs to be in the future.”

Sitting Beside is challenging and requires an investment. “Both parties need to honestly face current realities and challenges and opportunities for the future,” the guide says. But, in the end, Braskamp says, this type of assessment is useful and fair, to both the president and the institution.

Questions for boards

-

How much have past assessments of your chief executive focused on administrative style? On personality? On achievement of the institution’s mission?

-

Have past assessments focused on the identification of problems or on solutions?

-

In what ways can you make evaluation into a two-way street, strengthening both the board and chief executive?

For more information on this resource, contact the In Trust Center at (302) 654-7770 or resources@intrust.org.