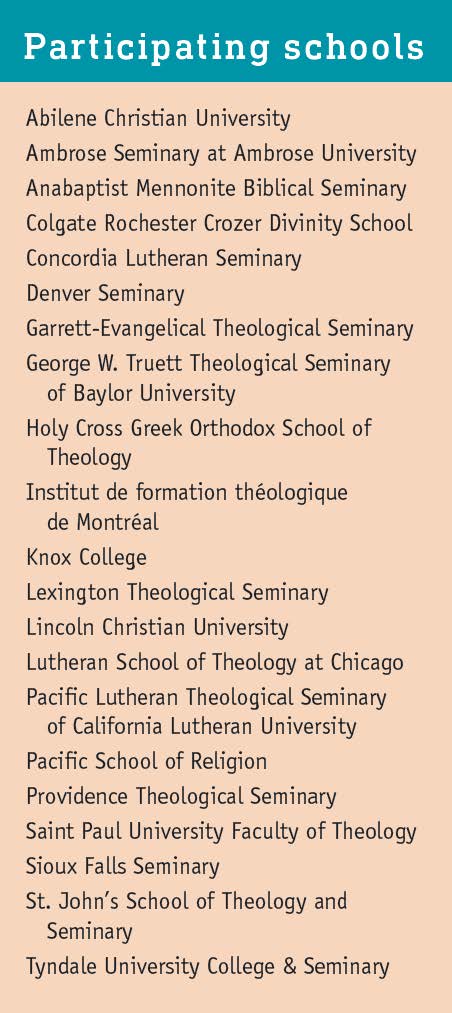

The Association of Theological Schools (ATS), in consultation with the In Trust Center for Theological Schools, recently sponsored a nine-month project to examine governance challenges. Throughout the academic year, 21 theological schools committed teams consisting of at least one administrator, one faculty member, and one board representative, who worked together with the guidance of a peer coach drawn from the ranks of veteran seminary leaders. At this final gathering, participants shared the lessons they learned through the process.

The collective insights of the schools serve to both affirm established notions of good governance and challenge the status quo with emerging ideas. They offered no particular surprises but rather recurring themes that constitute a checklist of 10 lessons for seminary leaders to keep in mind:

1Mission is the most important driving force in good governance. All stakeholders should be conversant with the mission and use it as a touchstone for evaluating the alignment of decision making with the school’s core purpose. From strategic planning to curriculum development to facilities management, decisions boil down to what kind of an institution a school aspires to be. According to former ATS executive director Daniel O. Aleshire, when thinking about what matters in good governance, “It’s not the buildings. It’s not the programs. It’s not even the people. It’s the mission.”

2 Personal relationships and trust are critical to success. As one faculty member said in reference to the relationship between faculty and trustees, “We have an ethical obligation to know each other.” Stephen Graham, senior director of programs and services at ATS, says that good relationships can help overcome poor structures, but the opposite is not necessarily the case. “A great structure can mitigate some relational issues, but structure cannot fully overcome obstacles without relationships,” he says.

3 Each constituency needs to be clear on its authority, responsibilities, and expectations. For board members, this can translate into not only a careful recruiting process but also a robust program of orientation that sets forth the complexity of theological education in general and the idiosyncrasies of an individual context in particular. For example, at Providence Theological Seminary, the governance team collaborated this past year on a board orientation curriculum that identifies specific milestones of engagement to define how new board members will develop in relationship with the school.

3 Each constituency needs to be clear on its authority, responsibilities, and expectations. For board members, this can translate into not only a careful recruiting process but also a robust program of orientation that sets forth the complexity of theological education in general and the idiosyncrasies of an individual context in particular. For example, at Providence Theological Seminary, the governance team collaborated this past year on a board orientation curriculum that identifies specific milestones of engagement to define how new board members will develop in relationship with the school.

The stated expectations for each constituency should include an explicit philosophy of governance that clarifies the intersection between management and governance and the role of all stakeholders, including denominational or ecclesial bodies where applicable. A visual representation of the structure can be especially helpful in communicating the roles and relationships. For board members, expectations about charitable gifts should be communicated up front. Advisory committees can serve as a helpful proving ground for prospective board members.

4 Communications need to be frequent, broad-based, and articulated in a common language. Sometimes good communication habits are born of crisis, but they should be maintained even after the crisis has passed. Among the suggestions: monthly communications from the president, complete with dashboard metrics and strategic updates, and monthly prayer letters. Regular reporting between meetings not only builds trust, but it also promotes board engagement and allows for more generative thinking when the board meets face to face.

5 Establishment of basic practices and processes helps to ensure a consistent governance structure that is more readily passed along to the next group of stewards. Putting processes in writing supports good governance, and documenting board deliberations and actions through thorough minutes and disposition lists enables the board to track implementation of past decisions.

6 Don’t wait for a crisis to improve governance processes. The précis for this governance project maintains that “some systems that have worked well in the past are not working as well as they used to, and other systems that work well in stable times are strained in periods of rapid or substantive change.” Sometimes it takes a report or focused visit from the ATS Board of Commissioners to call attention to a systemic governance issue. But a proactive assessment of how responsibilities are distributed and how decisions are made can catch issues before they come before the accreditors.

7 Look ahead. Boards should work closely with their administrators and faculty to stay abreast of current trends in theological education and to anticipate the next challenge on the horizon. “We should be focused not only on securing what we already have, but also in working toward thriving innovation for the future,” suggests a faculty member from Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary. “What does governance mean in a time of change?” asks Dennis Smid, a board member at St. John’s School of Theology and Seminary. “We always govern in times of change, and we have to reconcile ourselves to that.”

8 ATS standards serve as a useful benchmark for evaluating governance structures and processes. Standard 7 of the ATS General Institutional Standards begins this way: “Governance is based on a bond of trust among boards, administration, faculty, students, and ecclesial bodies.” It then sets forth the expectations regarding how institutional stewardship and authority are distributed among the board, the administration, the faculty, and the students. Yet effective governance requires a shift in thinking from simply satisfying a standard to focusing on becoming a better seminary.

9 Be nimble enough to respond to changing times with appropriate adjustments in governance structures. For instance, when not specified by your school’s bylaws, the number of standing committees can be streamlined, responding to immediate priorities with targeted task forces that are assembled to solve a particular problem and are then disbanded. Smid, the board member at St. John’s, reports that his school responded to declining student population by pulling enrollment out of the academic affairs department and assigning a special committee to focus on the issue. Stuart Macdonald, a faculty member who serves on the board at Knox College, shares that his working group was surprised to learn that it is possible to complete a project around a key issue in a one-year period — a model the school plans to use again.

10 This work is never done. Aleshire points out that many of the issues that schools are dealing with are the same issues schools faced when ATS was founded 100 years ago. And with ongoing turnover in faculty and board members, relationships of trust and common understandings must be continually developed. “Good governance takes time,” says Amy Kardash, president of the In Trust Center for Theological Schools. “It’s a journey, not a destination.”

An earlier version of this article appeared in the May 2017 issue of the ATS newsletter, Colloquy Online. It is available at bit.ly/GovernanceChecklist.