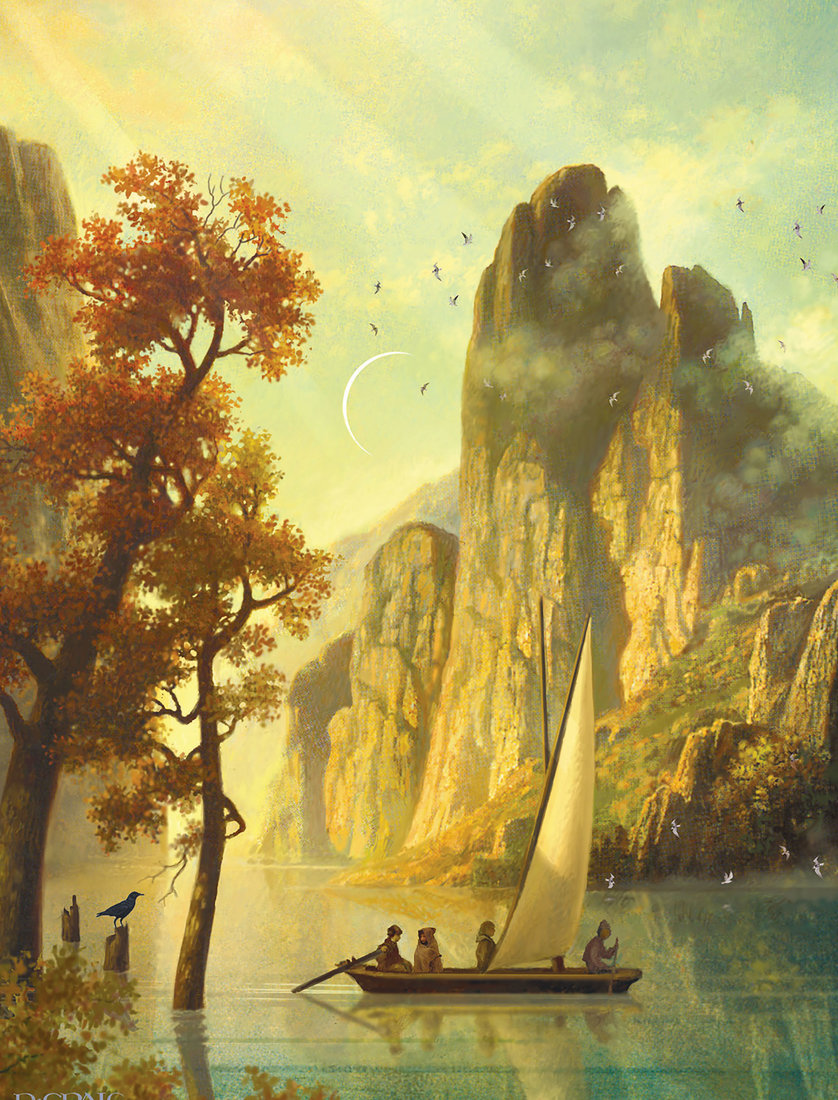

Throughout history, pandemics have created moments of pause, renewed energy, and hope.

In the early summer of 430 B.C. — the second summer of the Peloponnesian War — the Spartans had besieged Athens. Some 350,000 people from nearby villages sought refuge inside the city’s walls; while outside, the Spartans poisoned wells, destroyed villages and farmland, and cut down the Athenians’ olive orchards, their greatest agricultural resource. Conditions inside Athens were desperate: Food was scarce, hygiene poor, and a contagious disease spread like wildfire through the crowded city, killing a third of the population over the next three years.

“Terrible was the sight of people dying like sheep through having caught the disease from nursing others,” wrote Thucydides, the Athenian historian and military general. “When people were afraid to visit the sick, they died with no one to look after them; there were many houses in which all the inhabitants perished through lack of any attention…. The bodies of the dying were heaped one on top of the other and half-dead creatures could be seen staggering about in the streets, or flocking around the fountains in their desire for water. The temples in which they took up their quarters were full of the dead bodies of people who had died inside them.”

Pandemics have plagued humanity since ancient times. Thucydides himself contracted the plague, and, although he gave a nearly clinical description of the symptoms and course of the disease, it has never been definitively identified. Physicians were unable to help the afflicted because they could not fathom the cause of the novel disease.

The Athenian plague that took place 2,500 years ago was the first epidemic described in human history. If it sounds somewhat familiar, that’s because it highlights characteristic features of historic pestilences, including our own continuing struggle with COVID-19: the virulence of an epidemic disease when it attacks a society for the first time, the high mortality rate, and the social and moral dislocations that it produces.

A brief survey of the history of plagues and pandemics reveals that the perplexing questions facing us today are far from new. They are merely new to our generation. And, difficult though it may seem, we can learn from societies that have endured plagues in the past and from the evolving approaches and understanding of God’s presence in the world by Christians and other religious groups called to respond with faith, humility, and compassion. We can also take heart in the creative energy periodically released in the wake of past plagues, evidenced in significant advances in medicine, the sciences, literature and the arts, religion, and human rights.

Breakdowns and breakthroughs

Throughout history, pandemics have caused political, military, economic and religious upheaval, and often the collapse of societal norms and traditional moralities. During the Athenian plague, the afflicted prayed to the gods for help, but when the disease continued unabated, they concluded that their prayers and offerings were impotent. Demoralized Athenians turned to pleasure-seeking, lawlessness, extravagance, and erratic behavior. People ignored traditional burial rites, so important in Greek religious piety, and cast the bodies of the dying or dead into the streets. Many held orgies, pursuing pleasure since they might not live long enough to deal with the consequences.

Some 500 years after the Athenian plague, and continuing well into the eighth century after Christ, a series of pandemics in the Roman Empire was similarly devastating and caused terrible tolls in the large cities. The Plague of Cyprian (A.D. 250–c. 270), named for the bishop of Carthage, claimed 5,000 people daily at its peak, the lives of two emperors within 20 years, and many soldiers from the Roman legions, weakening the empire both politically and militarily. The fledgling Christian community, already persecuted, took the brunt of the blame. Yet Cyprian, who described the period, called on Christians to come to the aid of their persecutors and to care for the sick. He appealed to rich and poor alike for help: The rich gave of their substance, while the poor were called upon for service. He urged that no distinction be made in ministering to Christians and pagans alike.

For his efforts, Cyprian was repaid with exile in 257, and shortly thereafter he was martyred. But the activity he urged of the early Christians, which included offering the possibility of rewards in the afterlife, ultimately helped to spread Christianity through the empire.

Half a century later, the bubonic plague arrived in three great pandemics spanning the sixth through the eighth centuries. But the most infamous was the Black Death that first afflicted Italy and then all of Europe between 1347 and 1351, with occasional outbreaks for some 300 years afterward. After the Great Plague of London hit in 1665, it all but disappeared, a victim of its own success. A pathogen that kills its hosts will eventually run out of them.

The Black Death produced a wrenching break in the continuity of life. Food supplies ran short because there was no one to cultivate the soil. Schools, universities, and hospitals were closed because there was no one left to operate them. Crafts died out in places where they could not be passed on because of the death of guild masters who could teach their skills to apprentices. Wages went up, since labor was scarce, and prices soared, in many cases doubling. Ultimately, the plague hastened the breakdown of the feudal and manorial systems, creating a critical shortage of farm labor, and peasants demanded higher wages.

The Black Death hastened the decline of traditional values and the breakup of behavioral patterns that had lasted for hundreds of years. The resulting growth of cities proved crucial to the development of the Italian Renaissance, one of the greatest outpourings of knowledge and invention in European history. Physicians began more empirical studies of human anatomy and disease. Innovations in the sciences, art, architecture, music, and literature

In England, a university student was sent home from Cambridge in 1665 to his widowed mother’s farm to avoid contracting the plague. While at home for a year and a half between 1665 and 1667, young Isaac Newton made the three great discoveries for which he became famous: the essentials of calculus, the observation that white light is a mixture of colors, and the law of gravitation — all crucial to the development of modern science.

Science and social division

The smallpox epidemic, called “the most terrible of all the ministers of death” by English historian Thomas Babington Macaulay, was responsible for more deaths in history than any other disease. By the 17th and 18th centuries, it was causing 400,000 deaths each year and more than one-third of all the cases of blindness on the European continent.

Boston Puritan minister Cotton Mather (1663–1728) championed smallpox inoculations in 1721 during an outbreak in New England. At the time, most physicians as well as the press opposed variolation (an early form of vaccination) on the grounds that healthy people were being deliberately infected with a known disease, and some colonies passed laws against it. But several members of the local Boston clergy supported Mather, and by mid-century his chief critics — notably physicians and the press — had come to endorse the procedure.

During the latter half of the 19th century, the germ theory of disease stimulated bacteriologists to search for microbial causes of most diseases. Theological explanations diminished for most, replaced by medical explanations that offered a better understanding of discrete diseases, though not necessarily of the means to control them. But it did not wholly displace religious theories, especially when the “Spanish” influenza outbreak of 1918–19, which took more lives than World War I, shook confidence in the apparent medical security of the modern age.

For many of us, the medical crises posed by COVID-19 — from the isolation of quarantine to illness, loss of loved ones, and loss of jobs and livelihoods — are unlike anything we have previously faced. Indeed, this type of major public health crisis is unprecedented in our times, leaving many of us feeling ill-equipped to face its pressures. We may agree that science should guide our response, but the problem of balancing the interpretation of data from the scientific community and the needs of the economy divides us. The divisions over political and social issues already extant in American society have been exacerbated by the threatening epidemic, seen perhaps most clearly in our decisions to wear, or not to wear, protective masks.

Moreover, self-imposed quarantine has caused people to retreat into private spaces (their homes) and virtual communities, where their existing biases are reinforced. The ensuing stress and isolation, as well as conflicting reports from the news media, has led to the polarization of viewpoints and opinions. In the United States, longstanding social tensions have given way to protests, which in some cases have erupted into riots. The underlying social and racial pressures are not new, but COVID-19 undoubtedly has contributed to the severity of popular response. Many people have turned to their religious communities, but these have exhibited similar disagreement regarding how and when to resume meeting, whether to require masks in services, and whether to permit singing and communion.

Camus and the theodicy of pandemics

Throughout history, religious teachers in every culture have attempted to help people account for suffering. We call these attempts theodicies. Plagues in particular tend to produce religious explanations of their ultimate purpose and meaning, and even though Christian theologians have traditionally accepted disease’s natural causality and God’s providential purposes in it, epidemic diseases have been popularly viewed either as evidence of God’s wrath or as signs portending the end of the world.

Few modern works of fiction have so deeply explored the human response to the inexplicable pain and suffering caused by a pandemic — and the issue of ultimate cause — as Albert Camus’ The Plague. Published in 1947, the novel describes a devastating plague in the North African city of Oran. Father Paneloux, a Jesuit priest, is well read in the history of epidemic disease and in the literature of Christian theodicy. Early in the onset of the plague, he delivers a homily in which he presents a conventional theological approach. God sends plagues to call sinners to repentance, he says, and to lead those struck by the plague to a deeper spiritual life that is sometimes the result of their suffering. He warns his congregation that, failing repentance, they will be “winnowed, like corn on the bloodstained threshing floor of suffering and … cast away with the chaff.”

Theodicies do not always comfort the afflicted, and indeed, Father Paneloux seems to be speaking above — not to — the suffering of his parishioners. Yet later he draws closer to the suffering caused by the plague. He witnesses his parishioners’ pain and the horror of an epidemic that invariably brings death to those it afflicts.

In a second homily, the triumphalism and moralism of his earlier sermon are missing. Particularly distressed by the affliction of the children around him, he identifies with their suffering, and his compassion is the fruit of his participation in his parishioners’ pain. He plunges into the wretched humanity of those who suffer. And then, within two weeks, he contracts and dies of the plague.

A call to compassion

The growth of Camus’ Father Paneloux may not guide our behavior during COVID-19, but it may serve as inspiration for the kind of understanding and compassion to which God calls us in these times.

The suddenness of the threat — and the inability of both individuals and society to meet and conquer an unfamiliar phenomenon like COVID-19 — seems strangely incompatible with the high level of medical science and technology in our own century. It hardly seems possible that we are experiencing threats of the same seriousness as have accompanied nearly all previous epidemics. And like the fictional plague of Oran, this epidemic does not come with its meaning apparent. Rather, it brings unforeseen consequences. The alienation of our friends, and the divisions that characterize our society, as well as the upending of our plans for the future, force us to a new level of introspection. And with it come unexpected positive factors.

Whatever its ultimate meaning, the pandemic stops us in our tracks. We have time to reclaim the spiritual life that is often lost or diminished by our busy lives in a workaday world. It gives us an unexpected opportunity to step out of the all-consuming demands of everyday life, and to reflect on weightier matters. These are issues that we often banish from our thinking: the purpose of life and the inevitability of death.

For these reasons it is hard to imagine that the marked intervention in our daily lives is not, in whatever way we wish to define it, a divine visitation.

Gary B. Ferngren, Ph.D., is professor emeritus of history in the School of History, Philosophy, and Religion at Oregon State University.