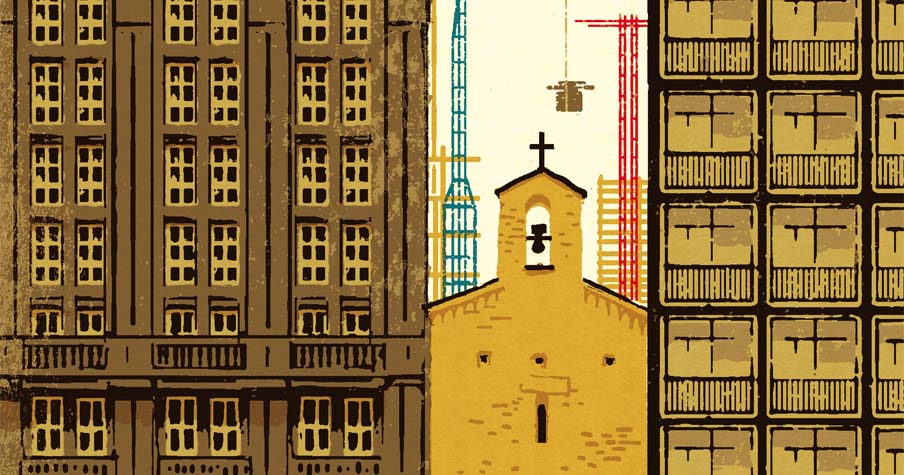

Illustrations by Pep Montserrat

This is hard, weird work,” said Mary Hinkle Shore, rector and dean at Lutheran Theological Southern Seminary (LTSS) of Lenoir-Rhyne University. “I love being embedded, but we’re on our third organizational chart. Combining a culture takes time.”

This story has had its bumps, as almost every story of embedding does. Shore, who was appointed to her position in 2019, recalled the first advisory council meeting she attended in her new role (LTSS’ advisory council is a committee of the university’s Board of Trustees, and the chair of the advisory council serves on that Board). The first order of business was the advisory council chair standing up and explaining to everyone how a governing board is different from an advisory board.

The explanation came seven years after embedding.

“There was a lot of confusion and frustration,” said Shore, who doesn’t believe much orientation happened for the board at the time the seminary joined Lenoir-Rhyne in 2012. The advisory council would come to campus twice a year, hear reports and then head back home, often hungry for a meaningful task to do. One woman was so eager for a job, she offered to write thank you notes, remembers Shore.

“We’re in a much better place now,” Shore said. “We are asking, ‘What is the purpose of the advisory council?’ ‘How are we drawing people in?’”

Questions such as these are crucial for any embedded seminary to ask, and the answers can be as varied as the differences between what embedded looks like in Otterburne, Manitoba, and how it is lived out in Dallas, Texas.

The Association of Theological Schools does require such a council or board to exist, but ATS is very aware that it might look different everywhere. Standard 9.1 of ATS Standards for Accreditation states, “A school embedded in another entity has some group that attends to the theological school’s mission, such as a board committee or an advisory council, and documents that group’s authority and responsibilities.”

Barbara Mutch, ATS senior director of accreditation, confirmed that embedded boards or councils “take so many different forms. For some schools there might be an advisory council that functions as a committee of the governing board. In others, it might not be part of the overall board trustee structure, and might be a group that champions the seminary, and helps with recruiting and fundraising,” Mutch said.

What is essential, whatever the model, is that the group is a structure that “can help ensure the thriving of the smaller unit,” which is almost always the embedded seminary. “It is to ensure the well-being of the seminary, to ensure there is some accountability and care so that the embedded body is well-looked after, well-resourced and contributing to the larger mission,” Mutch said.

Shore is right. Governance in embedded schools can be hard, weird work.

Enduring Change

Lutheran Theological Seminary’s Advisory Council is a committee of the Lenoir-Rhyne University Board – its third governance iteration since 2012.

Perkins School of Theology’s chapel once anchored the central quadrangle of Southern Methodist University; today, Perkins is one of seven academic units at SMU, with a sizable advisory board.

Wesley Seminary at Indiana Wesleyan University has an advisory board with oversight authority as a subcomittee of the university’s board.

Providence University College & Theological Seminary in Manitoba is overseen by the institution’s board; an advisory council includes primarily pastors.

Trinity Lutheran Seminary was embedded at Capital University in 2018; its board is now an advisory council, whose chair is on the university’s board.

Baylor University’s George W. Truett Seminary is one of the institution’s 12 academic units; the seminary’s Board of Advocates is primarily philanthropic.

Perkins School of Theology: A Work in Progress

The brick and stone Georgian-style chapel of Perkins School of Theology sits in the center of the “theology quadrangle” of Dallas’ Southern Methodist University (SMU). It is the cornerstone of the school of theology that has existed there since the university’s founding in 1911.

“The university has grown exponentially over the years, so the seminary is not physically or economically at the center of the university in the way it was before,” said Craig Hill, dean of Perkins, “but the university still considers (the school) a major part of the university and its mission. More than any other entity, we’re the ones holding up the church relationship and making it something tangible.” The other entities are the seven other degree-granting professional schools; the seminary was the first.

Perkins is the oldest and the smallest school within the university. “One of the best things about SMU is all of the deans are friends, we’re together frequently,” said Hill, who extends the friendship theme to cover Perkins’ Executive Board. “I view them as my friends.”

Hovering between 30-40 members at any given time, the Executive Board (as Perkins’ advisory board is called) is a mixture of volunteers who range in age, profession, gender, ethnicity, retirement status, clergy and lay people, all of whom share a commitment to seeing Perkins and its mission thrive. Some of them are also very well connected. “We’ve had (The New York Times columnist and author) David Brooks twice” at Perkins’ events, said Hill, with the help of a board member. Popular author Anne Lamott was another big draw at an annual event to benefit Perkins. “The board makes connections for us to worlds outside academia and outside church, and we’ve time and again benefited from those connections.”

It’s not just about who members know, of course, nor is it just about their ability to donate, but making the board’s role larger than those more obvious things takes some strategizing.

“It’s a work in progress to find ways an advisory board can do real work, and not just be there to help financially,” Hill said. “I’ve tried to have our board members not just show up and get reports and have good meals. But we do have to make it clear to new members that they’re not going to be making key decisions.” As Hill pointed out, as dean of one embedded school of many, that is also true for him. “I too am a man under authority, and I report up the chain.”

Bishop Michael McKee of Plano, Texas, is chair of the Executive Board. “No one comes to the board thinking they’re making decisions. The orientation has been very clear about there being no governance,” McKee said. “They’re coming to offer wisdom. We’ve been able to use that in a very good way.”

In his career, Hill has served in three embedded schools. He sees the shift to embeddedness as one that will continue to grow. “You’re part of a large system that’s more robust, you have their infrastructure to lean on, you don’t have to create everything yourself,” he said, listing some of the benefits, while acknowledging there is no perfect situation for theological schools today. Challenges abound everywhere.

“It’s always good to talk to people who are in similar situations. Conversations about what advisory boards can do is helpful because we can pick up ideas from each other,” he said.

Hill particularly enjoys hearing from schools that don’t have the long history of being part of the university, like Perkins, but have moved more recently from free-standing to embedded. “It’s fascinating to hear them talk about the ups and downs, and as they say in church, ‘their prayers and concerns.’”

Trinity Lutheran Seminary: Serving Two Masters

There have been ample prayers and concerns in the journey of Trinity Lutheran Seminary to become a healthy, embedded school of Capital University in Columbus, Ohio. Kathryn A. Kleinhans, dean of Trinity Lutheran Seminary at Capital University, and Pamela Bauser, advisory board chair, have been on the frontlines of trying to smooth out the ups and downs and make straight the path to positive embeddedness, and what that means for an advisory board.

“I came at the time of embedding,” said Kleinhans, on Jan. 1, 2018. “I’m the dean, just like there is a dean of the law school here and dean of nursing.” One of the challenges though, has been for the university to live well with the reality that a seminary is distinct from the other schools on campus because of its external relationship to another large body of accountability and concern, which is the Church. “There’s an attempt to make the seminary like any other school when it can’t be because we have this ecclesiastical network. I think sometimes it rubs people the wrong way.”

Bauser, a 1976 graduate of Capital who has served as chair of the advisory board since May 2020, said it’s “like putting a round peg in a square hole.”

There have been board issues to resolve: The chair of what transformed from a governance board to an advisory board when Trinity embedded, now sits, by bylaw, on the host university’s governing board of trustees. From Trinity’s perspective, that was a voice for the seminary. From the larger board’s perspective, it was about serving the university. “It’s about understanding the roles and keeping everyone in their places,” Bauser said. “We hit all the potholes.” Capital also entered a financial crisis at the time of embedding, which Bauser feels made the acquisition of the seminary seem less like a blessing and more like another financial burden. It was bad timing. Bauser worked hard to push back at the perception that Trinity, with its healthy endowments, was a destabilizing financial force for the larger school. There were small hiccups like acquiring extra parking spots for seminary students who have families and losing control of the timing of when financial aid packages arrive for their own students.

“It’s about understanding the roles and keeping everyone in their places. We hit all the potholes.”

“Embeddedness has a great deal of potential,” Bauser said. “It’s when you hit the day-to-day and how things function where it gets caught into turmoil.”

Some turmoil existed at the advisory board level. “When I started, the advisory board was 100 percent the same membership of what had been the governing board, so another issue was people wrapping their minds around a new way of doing things,” Kleinhans said. During a post-acquisition visit from ATS, they received the helpful advice to change the membership of the board, to help usher in a new era.

“There is recruiting of not only students but also those who will be good advocates for the board,” Bauser said. For Trinity, 15 is the magic number of members. “We’ve had to work diligently to get there. They come fresh, and come with questions,” she said. “The bigger issue is ‘how are you going to gather these people and what do you want them to do?’ It was perplexing, and people want to have a more defined role.”

These days, Bauser said, the advisory board is becoming more comfortable in its own shoes, which is also true for her role on Capital’s governing board. “I’ve had to become fully a trustee,” she said. “I’ve had to earn my keep, do the work, show up at meetings and then just keep bringing in the piece about the seminary and having conversations with people.”

In the last year, through the In Trust Center’s Wise Stewards initiative, Trinity has been having conversations of remembering and retelling its own history, both distant and about the process of embedment, which is helping it find a way forward. “To hear the former chair of the advisory board and the chair of the alumni council share their stories has helped us,” Kleinhans said.

In “Five things for a high performing advisory board,” an In Trust Center resource, boards are advised to engage in re-telling of the “origin story” of the seminary as often as needed, to keep the ‘raison d’être’ of the advisory board fresh in the minds of volunteers, especially those more accustomed to a board with governance and fiduciary duties.

Trinity believes the story they are now in the process of recapturing, retelling, and recording will help their relationship with the host university as well. Back in 1830, Trinity Seminary actually birthed the university with which it is now reunited and – step by step – moving into the future.

Wesley Seminary: The Gift of Oversight

In April 2009, a seminary was born on the grounds of Indiana Wesleyan University (IWU). Wesley Seminary has grown to serve 500 students in 11 countries, enrolled in its online programs.

“We have discovered we’re not like a lot of other embedded seminaries. IWU gifted the denomination with a seminary, that was the posture,” Wesley President Colleen Derr said. On an organizational chart, Wesley’s advisory board appears as a sub-committee of the university board of trustees, but “they are really given the authority to run the school like a non-embedded school,” Derr said.

IWU’s Board of Trustees ratifies Wesley’s budget “and any constitutional thing the seminary does, but they really have entrusted the seminary board with the gift of oversight that would be typical of another kind of seminary,” Derr said.

Connie Erpelding, chair of Wesley’s board, concurred. “We have been given great power, with the oversight of (IWU) President (David) Wright and the Board of Trustees, to actually oversee the seminary like a stand-alone board. They ratify our motions, and we take the vision and mission of the university, but we get to tailor it for our seminary and craft a seminary that meets the needs of the Church and the denomination.”

Derr and Erpelding, through participating in Wise Stewards, soon realized that even in the wide sea of differences between embedded schools, the autonomy of their board still sets them apart.

“There is a lot of autonomy, while reaping the benefits of being embedded in a very healthy and large institution,” Derr said even the name “president” is not often seen with embedded schools.

“I noticed many of my peers have the title of dean and usually relate to the provost, where in this case the provost is my peer and we both report to the president,” Derr said.

George W. Truett Seminary: Among the Twelve Tribes

Over 1,000 miles away in the Waco, Texas offices of George W. Truett Seminary, part of the campus of Baylor University, Todd Still, the dean, argues that language matters. “Baylor University, writ large, has a board of regents, the regents guide the university, and we are under their governance. There is only one president, and one presidential cabinet,” he said. “I am a dean. I’m a middle-level manager. I report to a provost, who reports to a president who reports to a governing board.”

George W. Truett is one of 12 schools and colleges of Baylor. “I sometimes quip that we are small among the 12 tribes, but the truth is that Truett is an important part of Baylor.”

And Truett’s Board of Advocates is important to Truett. Here, again, language matters.

“This is not a ministerial board. This is really a philanthropic board, and a board that wants to help us tell our story. If we called it an advisory board, well, what are they advising about?’” Still said. “Do they have influence? Of course. Input? Yes. We want to hear from them. We may say, ‘Help us think through this challenge,’ but that’s not quite a board of advisors, it’s more a team of friends.”

The board is a team of friends who help the seminary make even more new friends. “Help us get connected with your networks so we can expand ours,” Still said. “This is an impressive group.”

Jeff Schmeltekopf is chair of the board of advocates. “Our role is important in understanding the school,” he said, “but primarily advocating for it, trying to bring students, trying to fundraise. You don’t have the authority to initiate change or make change, but you have the ability to influence change.”

Board meetings are about sharing information and hosting conversations. “Information is the coin of the realm. Good advocates are informed advocates,” Still said. Before 2018, there wasn’t a board of advocates at all; it came into existence after an ATS governance study on best practices. “It’s a model we created for our context,” Still said. “We’re looking for conversation. It would be disingenuous to hold out to folks that they might have a decision to make when they don’t. Authority and influence aren’t the same. But they do have influence, and that means impact.”

“I sometimes quip that we are small among the 12 tribes, but the truth is that Truett is an important part of Baylor.”

Providence University College & Theological Seminary: The Gift of Sharing

Winnipeg, Manitoba, is almost directly due north of Waco, Texas, and just outside Winnipeg is the town of Otterburne, home to Providence University College & Theological Seminary. The board of advisors at Providence Seminary also came about from an ATS study when David Johnson became dean of the seminary. (Johnson went on to become executive vice president and provost and was appointed president by the Board in 2013. He retired June 30; his successor, Kenton Anderson, is the seminary’s 15th president.)

One board governs both Providence’s university college and seminary. “We share the board, we share the president, the cabinet. We share a lot,” Johnson said. The advisory council Johnson launched offers input to the seminary directly and is composed primarily of pastors who share their thoughts on what the Church needs and what they think the seminary should be covering. “We ask them questions like, ‘What’s happening in your churches?’ and ‘How can we serve you?’” Johnson said.

An Accelerating Trend

Advisory Councils by any name within their embedded corner of the world are meant to be positive, contributing to the health of the seminary and the success of its mission. ATS’ Mutch said, “When it’s healthy it would be a collaborative identification of what structure works best for this particular institution and the needs of a particular embedded schools.” The concern for a healthy board in an embedded scenario will be of concern to a growing number of schools, according to ATS.

The trend to embed is not slowing down, with 41 percent of ATS schools now related to a college or university, according to Chris Meinzer, senior director and chief operating officer of ATS. And Mutch notes that every three or four months over the last decade another seminary becomes embedded.

“Very often there are financial benefits,” she said. Schools that have made the transition to embedding also cite mission cohesion and increased access to support and infrastructure as motivation.

“It’s hard to imagine that trend slowing down or stopping,” Mutch says. “And the models for a group or structure that can help ensure the thriving of the seminary are as varied as the models themselves.”