(Reprinted with permission from Commonweal, written by Joseph Fete.)

(Reprinted with permission from Commonweal, written by Joseph Fete.)

Religious art continues to exert a powerful attraction even in a secular age. Casting Jaroslav Pelikan in the role of curator for The Illustrated Jesus through the Centuries is a shrewd idea, and for the most part the enterprise succeeds. The Illustrated Jesus is actually an expansion or visual supplement to Pelikan’s well-received 1985 Jesus through the Centuries. Indeed, Pelikan advises the reader to return to the “text edition” for more complete exposition and documentation.

Happily also, the graphic art that has replaced so much of Pelikan’s 1985 text gives broader ground for theological reflection. Walk into any Orthodox or Eastern Rite church and the iconostasis transports you to heaven in time for the eternal liturgy. Much of the art reproduced in The Illustrated Jesus was inspired by or produced for Christian worship. Many of the Western paintings in this book existed previously as altarpieces, or continue to exist as wall or ceiling murals in churches and chapels, and help create the proper environment for worship.

Painting dominates the illustrations in this volume and they are beautifully reproduced. There is a good balance of Western and Eastern art, high and low, classical and popular. Mosaics and sculpture are underrepresented, perhaps because of the difficulty in reproducing them in a flat, printed medium. Western painting seems to predominate. In that regard, one is compelled to ask why pictures of the smoky and cracked frescoes of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel are used. Why not pictures of the brilliantly restored frescoes?

The attention that Pelikan gives Christian art in this book also reminds us of the importance of giving equal weight to both the literary and the monumental or graphic sources of our tradition. No scholar who offered an interpretation of an ancient civilization based exclusively on literary evidence would be taken seriously. History that analyzes a culture’s architecture and art is essential. Yet frequently these sources continue to be overlooked in theological investigation.

Of course, Pelikan’s book is not offered to the “scholarly” market. It is accessible to anyone. Unfortunately, the lack of proper identification for some of the pictures creates occasional confusion. In a composite icon Basil the Great is identified; but who are the other mesmerizing figures? In a chapter that recounts the monumental contribution to theology by Augustine of Hippo, this bishop and teacher is pictured with Gregory the Great. But who’s who? If one had access to a dictionary of iconographic symbolism one could figure such things out for oneself. Possessed of this tool one could also determine that, contrary to the caption, the Lindau Gospels do not portray the four symbols of the Gospels.

Devotional prayer and meditation as well as the sacred liturgy have relied on the efficacy of “visual theology” since the time of the catacombs. In an increasingly pictorial age, the science of theology may now be tuning in to this visual channel. The Illustrated Jesus sets before us a theological feast for the eyes and whets our appetite for more about sacred art that is less opaque, less like a theology written in a foreign language. This volume returns us to the knowledge that art is more than pretty pictures—it is a way of doing theology. It is our Christian tradition.

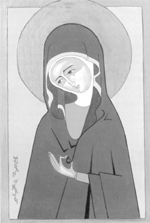

Illustration: Icon of the Lady Julian of Norwich by Anna Dimascio (c. 1980). Illustration from the Illustrated Jesus through the Centuries.