(Reprinted with permission from The Wall Street Journal, written by Laura Landro.)

(Reprinted with permission from The Wall Street Journal, written by Laura Landro.)

For years, we’ve been made to feel guilty about shopping too much and being suckered into it by designer labels, advertising slogans and brand names. Now, however, we can relax and enjoy it—it’s natural!

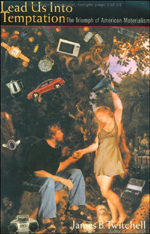

According to James B. Twitchell’s Lead Us Into Temptation, shopping, buying and flaunting our new stuff is the ultimate defining activity in modern society. In the milieu he calls “mallcondo culture,” the purchase of branded items not only tells others who we are, it helps us to find our own identity and gives us something to believe in. Shopping, in other words, is the “meaning-making act” of life today. The mall is the new Jerusalem.

Borrowing from an old Janis Joplin song, Twitchell rhapsodizes: “Freedom’s just another word for lots of things to buy.” He gleefully acknowledges that “one might well wonder if there is anything more to American life than shopping,” but to him this is a good thing: we shop to satisfy desires, not needs. (Once we are fed and sheltered and sexually productive, our needs cease to be biological and culture begins.) We buy that Porsche because we’ve bought into that advertising campaign and want to be part of the “legend.”

In this view, we have let ourselves be led into temptation because it’s just so pleasurable. And hey—we’re not being exploited—we’re being fulfilled! We like having stuff—Twitchell dismisses the idea that consumerism creates artificial desires: “Getting and spending has been the most passionate and often the most imaginative endeavor of modern life.”

Most readers of the business press know that marketers classify us into categories—groups like Money and Brains, Pools and Patios, Shotguns and Pickups—but Twitchell argues that we actually seek to cluster ourselves within these groups. We want to affiliate with tribes who drive the same cars and wear the same logos. We have traded knowledge of history and science for knowledge of brands and how brands interlock to form coherent social patterns.

How persuasive is all this? Twitchell, who teaches English and advertising at the University of Florida in Gainesville, is nothing if not thorough.

Lead Us Into Temptation is the third of his books on consumer culture and the media and could well be the text for a survey course on the subject. He has clearly made an exhaustive study of the literature on shopping, advertising, branding and packaging. He quotes liberally from other treatises and provides lots of studies, surveys and examples clipped from newspapers.

And one has to admit, there is something to what he says. Shopping is undoubtedly more than the simple act of satisfying needs or getting the biggest bang from our buck. There is plenty of evidence—Twitchell offers more than enough of it—that we do indeed feel some sense of affiliation and social pleasure from buying what others buy, or (in some cases) what others do not buy.

But Twitchell overreaches. He skewers anything that doesn’t support his theory that shopping and consuming define us, such as the recycling movement and the Voluntary Simplicity Movement. He also expresses a too-easy contempt for “reformed admen,” psychologists and other academics who say, not unreasonably, that “Things Can’t Buy Happiness.” And he disparages non-consumerist activity to the point of absurdity. In his view, the media—television, newspapers, magazines—exist merely as purveyors of advertising messages. The writer’s or reporter’s words on the page are mere “vanilla,” and TV programs are merely scheduled interruptions in an endless flow of marketing bulletins.

Needless to say, there is something profoundly cynical and depressing in this view of the human race, and something terribly misguided. Twitchell confuses pastime with purpose. Whatever pleasure shopping may give us, a good part of the meaning of life takes place between trips to the mall: say, at the family hearth or the neighborhood baseball game, or in the company of a book or a friend. People still care about politics, work, intimate relations. And not everyone has abandoned church for the mall.

Throughout, Twitchell draws parallels between consumerism and religion. Clergymen will no doubt be dismayed—understandably—at such assertions as: “Whereas the Heavenly Host organized the world of our ancestors, the Marketplace of Objects does it for us; they both promise redemption: one through faith, the other through purchase.” To Twitchell, “modern consumerism is not a replacement of religion but a continuation, a secularizing, of a struggle for order. Salvation through consumption is not a contradiction, but a necessity.” It takes a pretty shallow idea of religious belief, and of human spiritual yearning, to write such cant.

To put it diplomatically, Twitchell has seized on a few basic truths about consumerism and gotten completely carried away. But this much may be true: going out shopping might be more rewarding and fulfilling than reading a book about it.