For newcomers to the storm-tossed seas of money management the beginning of the twenty-first century has been a time for Dramamine. It’s been hard on “old salts” too, as nine of the top ten foundations in the United States suffered a combined loss of more than $8.3 billion in the first six months of 2002. The Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged more than 27 percent between January 2000 and November 2002 but it also surged 20 percent in a seven-week advance in October and November before sinking again in late November and December.

Investment markets have been nothing if not unsteady—yielding widely-varied results in data reported to the Association of Theological Schools—and challenging the theology of money managers everywhere.

Paradoxically, schools with smaller endowments may have fared better than their larger colleagues. For example, Thomas H. Graves at Baptist Theological Seminary at Richmond acknowledged immediately that the market situation is a problem, but explained only half-jokingly, “We are blessed by our poverty.” His seminary is young, relative to others, and without a large endowment, has less to lose. However, the seminary still must deal with reduced monies from the 5 percent draw on endowment that would have been counted on. “It means,” he said, “that where we would have depended on endowment funds we are now counting on operating funds to make up for that.”

His experience is similar to that of Michael Cooper-White, president of Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg, in Pennsylvania, who said that his institution, while not as endowment-dependent as many, still receives approximately 25 percent of its annual budget from investment earnings. “Prior to the recent market decline,” he said, “we had already imposed rather severe austerity measures and reduced expenditures by over 10 percent in order to balance our budget. This involved eliminating administrative staff positions, delaying faculty replacements, and reducing our capital budget expenditures.” In addition, the seminary has increased tuition by 25 percent within a three-year period.

“Fortunately,” he said, “significant enrollment growth coincided with market decline, enabling us to avoid further expenditure reductions thus far.

“Like everyone else,” he said, “we’re banking on market turnaround while monitoring very closely our expenditures.”

When asked how he thinks of these challenges theologically, he cited the mandate from Second Timothy 4:2, to urgently proclaim the gospel “whether the time is favorable or unfavorable.”

“I take it to mean,” he said, “that we must be faithful to our mission in lean financial times as well as when resources are more plentiful. As we have pared our expenses and sought creative resource development, I’ve maintained confidence that God is up to something, and that God is good all the time!”

“We are blessed by our poverty.”

|

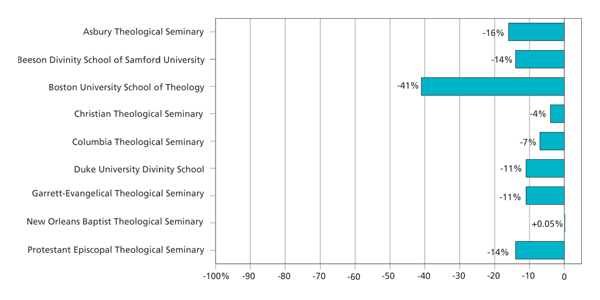

Percentages showing change in value of long-term investments were calculated from annual fiscal year data reported to Association of Theological Schools over the past three years; not all schools had reported at time of publication.

View a larger version of the above chart.

|

Across the country, Donn Morgan, president and dean of Church Divinity School of the Pacific, Berkeley, California, did not miss a beat when he declared, “Of course the market is a problem. While we have some very good money managers and are doing better than most others in terms of preserving capital, we have still lost a lot of money. The problem is clearly with our draw rate. With less money to draw on, but the same kinds of need, something has to give.

“Some of this is not moving forward with big spending plans that presuppose a bigger draw on endowment; some of this is risking the decrease of endowment value still further—you know the

options, and none of them are good. However, for whatever reasons, most of them involving a lot of faith, we have moved forward with a more aggressive and ambitious fund-raising scheme (both capital projects and an increased annual fund goal), matched by a rather large building project totally congruent, we believe, with the long term mission of our school. Is it a good time? No, but our financial advisors also point out there never is a good time. Is it realistic? I honestly don’t know, but big visions often draw big money, even in less than ideal financial times. Is it doable? That question remains to be answered but we have little to lose and much to gain, as long as we keep a balance between future visions and the need for fiscal stability in the present, and it’s more exciting and energizing to work toward goals which will make a huge difference for our school.”

In New England, Boston University School of Theology has been one of the hardest hit seminaries, with a decline in long-term investments of more than 40 percent since the market downturn. The institution, tied as it is to Boston University, is participating in the university’s overall effort to cut some 450 jobs that range through the ranks of administration, faculty, support staff, and custodial help. According to Dean Robert Neville, “The School of Theology has enough open positions that it can make its contribution to this saving merely by filling these positions in a slow and deliberate manner.” Further, the board of visitors of the School of Theology has agreed to advance the agenda for a capital campaign, but Neville says he lives with the “hope the American economy will recover more quickly than the time it will take to make a significant increase in the school’s endowment.”

Neville did note that alumni and alumnae “seem to be especially appreciative of our troubles and have been giving in record numbers.”

Edward L. Wheeler at Christian Theological Seminary in Indianapolis described his school as an endowment-driven institution but said, “Because we are fortunate to have a good board subcommittee minding the store, we have lost less than many institutions.

“The board has been extremely supportive and asked the tough questions,” he said. “In the last two years they have increased their own giving by 10 percent and have taken pains to introduce us to other donors.”

In contrast to Boston University’s situation, Duke University Divinity School dean L. Gregory Jones revealed that Duke’s 5 percent decline in endowment monies over the past two years was cushioned by the rapid increases in previous years. “Our expendable income from endowment is based on a three-year rolling average. So we are still benefiting from the growth in endowment three years ago.” He explained that Duke’s endowment increased by 57 percent, since the early 1990s, thus providing the cushion.

Nevertheless, Jones said, “We have been exercising greater caution as we project our plans for the future, and we recognize that some programs that we thought we could begin on the basis of endowment growth will now need to be funded through new fund-raising—especially for expendable funds and not only endowment gifts. But we have not had to undertake significant changes in our fund-raising strategies. Board members have been very helpful with gifts and in helping us plan ambitiously yet prudently.

“Even in tight financial times, we are called to think and operate out of a logic of God’s abundance,” said Jones, referring to Ephesians 3:20. “This will require tough financial decisions, but if we allow these decisions to drive us to a logic of scarcity, we will begin to think in terms of envy and lack rather than a life-giving vision of where God is calling us to go.”

At the Pacific School of Religion, President William McKinney said that his institution is seeing some benefit from their historically conservative approach to allocations. “Bond performance and hedge funds are helping us,” he says, “while equities are about 50 percent or less.” Working in the school’s favor is the fact that PSR is in the last stages of a capital campaign, $9 million of which will go into the endowment. But as far as everyday changes are concerned, McKinney noted, “We are more hawkish regarding expenses. Our issue has been excessive draw rate, so we are used to being in a conservative mode. Discipline has served us well. We work off a twelve-quarter moving average, so we think we are okay for 2003-04.”

Also, he said, he and his board have learned the virtue of patience, exemplified in their fund-raising by allowing pledges over three to five years.

His board chair, Scott Hafner, described giving by the board as a team effort, admitting that things are complicated now by the fact that the seminary is in a capital campaign. “Every trustee now has two giving opportunities,” he said, “and those of us close to Silicon Valley have experienced the shrinking portfolios of the high-tech companies.” Nevertheless, because of the board’s collegial philosophy “people have been lovely,” he said.

“If one trustee has been hit especially hard, the others understand that and will dig a little deeper and give more to compensate.”