The office of Alan Hayes, director of the Toronto School of Theology, boasts a beautiful, leafy view over Queen’s Park, an urban forest in the heart of downtown Toronto. Silver maple, northern red oak, and an equestrian statue of King Edward VII dominate the park, a green enclave within the University of Toronto. Worn paths connect one corner of the campus to another.

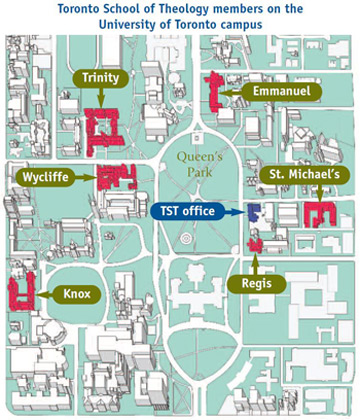

In fact, you can walk from Wycliffe College, an evangelical Anglican graduate school on one side of Queen’s Park, to the Toronto School of Theology offices on the other, in about seven minutes.

Theological colleges pepper this sprawling, downtown campus.

Trinity College (another Anglican theological school) is a stone’s throw away from Wycliffe, and four other schools are within a few blocks: Regis College (a Catholic faculty of theology run by the Jesuits), Emmanuel College (affiliated with the United Church of Canada), Knox College (part of the Presbyterian Church in Canada), and University of St. Michael’s College (another Catholic school, this one run by the Basilian Fathers). All are deeply connected to each other through their membership in the unique consortium that is the Toronto School of Theology, universally known as “TST.”

St. Augustine’s Seminary, the seminary of the Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto, is the seventh member of TST. And even though the main campus of St. Augustine’s is nine miles (15 kilometers) east of the University of Toronto campus, the seminary does offer some classes on the university campus as well.

The Toronto School of Theology is an address— 47 Queen’s Park Crescent East to be exact—but it’s also an ambitious idea linking together seven distinct theological traditions, boards, buildings, faculty, and students into a multilayered whole.

It’s complicated

“We are the most complicated piece in North American theological education,” says J. Dorcas Gordon, principal of Knox College.

There is a story told in TST circles about a visiting academic administrator who wanted to understand how TST worked. “He was taken on a tour and visited each site,” says Gordon Rixon, dean of Regis College. “After a three-hour tour, concluding the visit with the final college, the visitor said, ‘I think I’ve begun to understand this.’ His host replied: ‘I haven’t made myself clear. Let me start again.’ And that kind of sums it up,” laughs Rixon.

To begin to understand TST, one needs to understand what a consortium is and what it is not, says Martin Campbell, a Toronto lawyer who chairs the TST board. “It’s a group of people or organizations who come together for a common purpose. It’s not something that is all that common in legal parlance.”

In TST’s case, “it means the seven members give up only that part of their authority and power which is necessary to accomplish the common purpose, and they retain their separate identity,” explains Campbell. “That is a critical balance for TST—they all have their own heritage and are accountable to their own denominations and traditions. It’s that delicate balance that everyone has respected for more than 40 years. And the consortium could only function if that balance is respected.”

Location, location, location

It matters to that fine balance that the colleges are so close together, says Alan Hayes, director of TST. “This is the one consortium which is geographically compact. We’re on a common timetable. The annual calendar is the same for all. The weekly timetable is the same so it makes it very easy to take courses at different colleges. The other unusual thing is that all the colleges are formally related to one large university, which exercises a gravitational pull. Students all share the university’s registration system, student services, and academic regulations.”

It is not just the students who benefit from the colleges being an easy stroll away from one another. Proximity means everyone can get personal. The heads of the colleges meet regularly to discuss plans, issues, problems, programs, and everything else that comes up in the running of seven colleges that are distinct but unified.

“I’m called a director, which is a funny term,” says Hayes. “I don’t direct much. I’m the directee, someone who can keep all the different players in touch with one another.” He adds, “My job is to get all the players in continual conversation. The heads meet together once a month. The finance officers meet regularly; development directors meet regularly. So do the registrars and librarians and academic administrators and student leaders.”

The great thing about being a consortium, Hayes says, is “you are never exactly alone.”

One in seven, seven in one

Mark Toulouse is principal of Emmanuel College. Formerly dean of Brite Divinity School in Texas, he’s the newest principal on the block, and he felt the power of collegiality among the heads quickly. “The trust level that occurs between the heads of the colleges and the board has been crucial to us,” he says. “There is a strong level of trust between the seven schools and an ability to understand how we have our own needs, and that is a very effective way to operate.” George Sumner, principal of Wycliffe College, sums it up this way: “We get in the same room, eat lunch, and work it out.”

Communication and contact are key to making TST work for the heads of the colleges, for the boards, and, of course for the students who feel the consortium’s power both in the basic degree programs—those leading to the master of divinity, master of religious education, master of theological studies, and several master’s degrees in specialized ministry areas—and in the advanced degree programs— the doctor of philosophy, doctor of ministry, doctor of theology, master of theology, and research-based master of arts programs.

“The doctoral program is a single program housed in different colleges,” explains Sumner. “The master’s level is seven programs bound together in a single enterprise. At master’s level you have seven colleges which are by common commitment open to one another.”

In other words, the concentration of a basic degree student’s course work will be in one college, even though such students can choose from an extensive menu of classes—typically more than 500 taught by more than 300 faculty members across the seven schools.

But for advanced students, the collaboration is fully fleshed out. Students in these degree programs are enrolled in one specific college, but the committee overseeing their work has representatives from other colleges as well. “Advanced degrees are really run centrally, so each school technically admits its own students and grants degrees but doesn’t actually run the program,” explains Hayes. “The actual academic supervision is done centrally.” (To add to the confusion, M.A. and Ph.D. degrees are granted only by St. Michael’s College even though the programs are run through the TST.)

Shifting sands

|

| The seventh TST school, St. Augustine's Seminary, which is nine miles (15 kilometers) east of the University of Toronto campus, holds some classes at St. Michael's. |

Finding the best way to govern TST so that it doesn’t fray around the edges is the ongoing challenge of the director, the seven heads, and the board. And right now, the board is completing a process of realignment.

“The stakeholder model has been too cumbersome,” says Martin Campbell, the board chair. “We have had many, many meetings and a lot of duplication.” So at the board’s October meeting, a change was approved limiting the technical membership of the corporation to the seven schools as the ultimate stakeholders. “It will be a tighter board with control, quite literally, given to the seven schools,” he says.

And that subtle shift, says Gordon Rixon of Regis College, is “making the present reality more transparent.” The heads of the colleges already have most of the power on the board, and its new makeup will reflect that. “It will be a smaller board, more closely aligned with the colleges, so that in a sense TST really serves the colleges, and together we serve the public,” says Rixon.

And on a university campus in Toronto—a multicultural, global city in a post-Christian age—that is a very diverse public. How this consortium can potentially serve a multifaith community of students, while still respecting and reflecting seven distinct identities and missions, is an ongoing conversation at TST.

St. Michael’s has had a Jewish studies program for years, but more recently, multifaith education within the TST has expanded. In the basement of Emmanuel College, for example, there is a room with a plastic bin filled with colorful prayer rugs for Muslim students. An ablutions room is just down the hall for their use as well. Emmanuel offers a certificate in Muslim studies—not necessarily for Christians to study Islam, but primarily for Muslims to become better equipped to serve their own constituency.

“We have this Muslim studies program at Emmanuel, that has recently involved having a fulltime Muslim faculty member,” explains Mark Toulouse, the principal. “A Muslim faculty member doesn’t neatly fit into the history/Bible/ ethics/pastoral categories of TST. So, how do you get a faculty member approved with standing within the TST levels of governance? And then who approves the courses to be taught?”

Toulouse says it’s a matter of pushing the edges in new directions. “We’ve been able to figure ways to work these things in and make them work,” he says. “We need to be flexible enough to create the models to deal with the edges. It can take time.”

Time is something TST is willing to take. Consensus is crucial, says Alan Hayes. “And if we can’t get consensus, we wait.”

Dorcas Gordon of Knox College calls this particular dialogue “a wonderful conversation.” She notes that TST is in conversation with a yeshiva about the possibility of forming a relationship with the consortium. “What would it mean for TST to have schools that are not Christian?” she asks. “It’s a fantastic conversation, given that in the different schools there are different ideas of what ‘interfaith’ looks like and how it gets formalized.” It’s part of the air they breathe at TST, she says, but that doesn’t mean that everyone agrees on how interfaith relationships should be built. Diversity of opinion is an inherent part of the discussion.

And that, says Gordon, is the strength of TST.

Future programs and potential

How different faiths are included in TST is one important agenda item these days, but so is TST’s application for a conjoint Ph.D. program with the consortium’s mothership, the University of Toronto.

“A Ph.D. program would replace the academic doctoral programs that are currently in place, but all of this is in flux,” says Terrence Donaldson, a Wycliffe professor who is heading up the proposal to the university. “We’ve long wanted to grant a Ph.D. with the university, and the university is now in a position where they are open to that in principle and are prepared to welcome a proposal in that direction.”

Donaldson says that it is the nature of the TST consortium that has helped open the university to this possibility. “They’d be much more nervous if it was with a single denomination. It wouldn’t be possible for one college to go it alone. The U of T is willing to enter into that kind of relationship with a multidenominational consortium with a nondenominational umbrella structure.” He says that the TST consortium “stands as a model for ecumenical theological education, one in which each of the schools maintains its distinctive identity and represents its own strand in the broad Christian tradition.”

And don’t forget TST’s similarity to bumblebees.

Dorcas Gordon recalls the comments of an ATS representative, who wrote up a report after a TST focus group. “The writer of the report said that TST was like the bumblebee,” she explains. “There’s no reason why it can fly. But every day it gets up and flies.”

“And what keeps us flying,” says Gordon, “is our commitment to sit at the table and work out the differences and the challenges.”

Sample questions for boards

If your school is already part of a consortium

-

Board. Does your consortium have its own board of directors? If so, would it be better if the consortium board were smaller — or larger? How are consortium board members selected? Does your selection process bring you candidates with the skills, experience, and knowledge that the consortium needs?

-

Academic integration. Identify the ways in which academic programs are integrated. In what ways might it be useful to integrate the academic programs of consortium members even further? What would be the costs of doing so?

-

Administrative integration. What administrative functions are shared by members of the consortium (for example, library, admissions, student services, food service and auxiliary enterprises, academic scheduling)? Would further integration present opportunities for further efficiency? What obstacles would you face if you moved toward integrating additional functions?

If you’re considering a merger, partnership, or alliance with another school

-

Nature of collaboration. What kind of collaboration are you considering? A consortium with several other schools? An affiliation with a university? A consolidation with a freestanding seminary? The exact nature of your agreement must be worked out individually and will probably be unlike any other partnership.

-

Board integration. Will your agreement require the creation of a new board? Will each of the partnering schools retain their independent boards? Or will the boards of the partnering institutions merge into a single new body? How will this take place?

-

Get a guide. Do you have a shepherd to help you through the process? Pursuing a partnership or merger with another school presents many opportunities, but there are also pitfalls galore. The buy-in of all presidents and board chairs of the partnering schools is essential, but most schools also find that they need an experienced coach or consultant to help out.

For more on consolidations and mergers, including a typology of different kinds of partnerships, see www.intrust.org/consideringalliance. For an analysis of the pitfalls of partnerships, see www.intrust.org/partnerships.