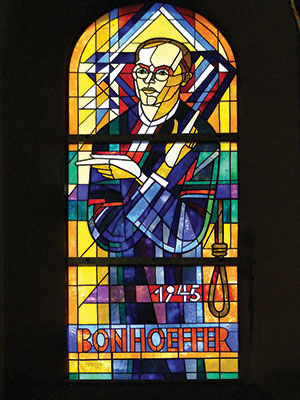

In response to Hitler’s threats to the church in 1930s Germany, alternative seminaries were established in 1935 by the Confessing Church movement. These schools were banned — first by the pro-Nazi Protestant bishop Ludwig Müller, and then by the state itself before the end of 1935. But until 1937, the underground seminary at Finkenwalde continued to operate independently. Within this pressurized context, its director wrote enthusiastically that the summer of 1935 had been “the fullest time of my life, both from the professional and from the human point of view.” Dietrich Bonhoeffer is famous today as a theologian, pacifist, and Confessing Church leader — he was a writer, teacher, double agent, prisoner, and martyr. But we should also recognize him as a seminary director.

In response to Hitler’s threats to the church in 1930s Germany, alternative seminaries were established in 1935 by the Confessing Church movement. These schools were banned — first by the pro-Nazi Protestant bishop Ludwig Müller, and then by the state itself before the end of 1935. But until 1937, the underground seminary at Finkenwalde continued to operate independently. Within this pressurized context, its director wrote enthusiastically that the summer of 1935 had been “the fullest time of my life, both from the professional and from the human point of view.” Dietrich Bonhoeffer is famous today as a theologian, pacifist, and Confessing Church leader — he was a writer, teacher, double agent, prisoner, and martyr. But we should also recognize him as a seminary director.

It’s easy to see how Bonhoeffer’s years in seminary leadership shaped his theology. In fact, two of his most popular works came out of his Finkenwalde experience: Life Together and The Cost of Discipleship.

When Bonhoeffer arrived at the seminary in 1935, the needs were daunting. Students and faculty lacked books, furniture, and money. Sound familiar?

Bonhoeffer’s responsibilities were also enormous. He visited local congregations, raised funds, and worked with local church leadership. He was essentially the sole administrator, a position that allowed him to envision an experiment in Christian community — a completely different education than his own student days at the universities of Tübingen and Berlin.

As the head of the Finkenwalde seminary, Bonhoeffer both established the curriculum and shaped a rule of life for his students, including:

-

A structured daily schedule, including worship, meditation, meals, work, study, music, and recreation, and even the public reading of books at mealtime.

-

A formal syllabus of ministry courses.

-

His famous course on discipleship, which became a nerve center for the whole institution.

-

Lectures, discussions, books, and tracts for students and church leaders on “public theology” — weighty issues in the church, the state, and the world.

As an administrator, Bonhoeffer balanced ecclesial responsibilities (like ordination requirements) with the local everyday needs of the seminary (such as food, maintenance, and budgets). But the most notable aspect of his leadership was his accessibility to his students. He kept nothing to himself — not his books, his records, his car, or his weekends.

The director’s role provided Bonhoeffer with the opportunity to fulfill one of his deepest spiritual dreams, living within an intentional Christian community. It didn’t take long until the positive and negative press started to fly. The Evangelical Church throughout the country started buzzing, with some commentators praising the underground seminary’s powerful innovations and others denouncing its “terrible heresies”: “Catholic practices,” pacifism, and radical fanaticism. His own students were particularly shocked by the practice of individual confession and absolution as a community — which included confession by Bonhoeffer himself!

Why is studying Bonhoeffer important? The role of the seminary president is developing in fascinating ways. To do their jobs well, presidents need role models both contemporary and historical. One way to gain inspiration is to study seminary leaders like Dietrich Bonhoeffer whose life and writings, though unique, are filled with inspiration and insights for the modern president. How is your seminary an example of Christian community?

How is your institution forming students for a life of discipleship and public witness in times that are politically and ecclesiastically troubled? Bonhoeffer challenges seminary leadership to ask these questions and many more.