| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Piety and Intellect: The Aims

and Purposes of Ante-Bellum Theological Education (Scholars Press, 1990, 458 pp.)

|

Piety and Profession: American Protestant Theological Education, 1870-1970 (Eerdmanns, 2007, 845 pp. $52)

|

Piety and Plurality: Theological Education since 1960 (Cascade Books, 2014, 406 pp., $45)

|

I did not expect to read about the rise of the automobile in a history of seminary education. But Glenn Miller’s three-volume history of American theological education is full of surprises. A monumental achievement in both quantity and quality, Miller’s work is more than an institutional history of American seminaries — it is a history of American Protestantism told through the story of the institutions that train Protestant clergy.

Miller details the history of structures, forms of governance, and professional organizations, but this is only a small part of his sprawling narrative. At every turn, he embeds the story in the broader religious and cultural changes that have taken place in the United States in the past two centuries. Miller leaves no stone unturned to explain how and why American theological education has developed in the way it has, and how it has functioned within the broader structures of American religion and culture. As for the discussion on cars — well, you would be surprised at the number of seminaries that have moved from campuses accessible by rail and streetcar to more automobile-friendly locations far from the nearest train station.

This massive work could easily become unwieldy, and at times, particularly in the second book, it does. Miller admits this in his preface to the last volume (Piety and Plurality, xv), where he writes that the previous volume was “too long for all but the most dedicated reader to complete.” The series as a whole will probably be used more often for reference than as a consecutive narrative. But the remarkable thing about Miller’s accomplishment is that a clear narrative does emerge from the mass of detail.

The rise of the mainline consensus

The drama has three acts, well-marked by the three volumes. The hero of the story — a tragic hero, as it turns out — is what Miller calls the “professional model” of ministry, whose rise is recounted in immense detail in the second volume, Piety and Profession. This volume, central to the series in more ways than one, begins after the Civil War and covers the next century, culminating in the flourishing of the mainline churches after the Second World War. During this century, the major Protestant denominations moved away from much of their earlier infighting and constructed ecumenical structures that reflected certain common assumptions about the nature of faith and the role of faith in society. The social gospel of the early 20th century provided the intellectual framework for these assumptions. Churches were to be agents of the Kingdom of God by agitating for social change, promoting values of justice and compassion, and providing a wide range of social and educational services themselves. This vision of the Church was most fully embodied, on the local level, in the urban “institutional churches” — large downtown complexes with specialized staffs providing opportunities for worship, fellowship, education, and general social uplift.

Seminaries were an important part of that process. The post–Civil War seminary quickly became an institution defined by professional norms that were, in principle, independent of the specific teachings and practices of particular denominations. Academically, these norms were shaped largely by the intellectual and institutional traditions of the German university, translated into the rather different American context. Culturally, they were shaped by an optimistic vision of the church as the moral arbiter of society. Protestants in what would come to be called the “mainline” denominations expected their clergy to be equipped to give moral guidance to their communities as those communities wrestled with the difficult social problems of modern industrial society.

|

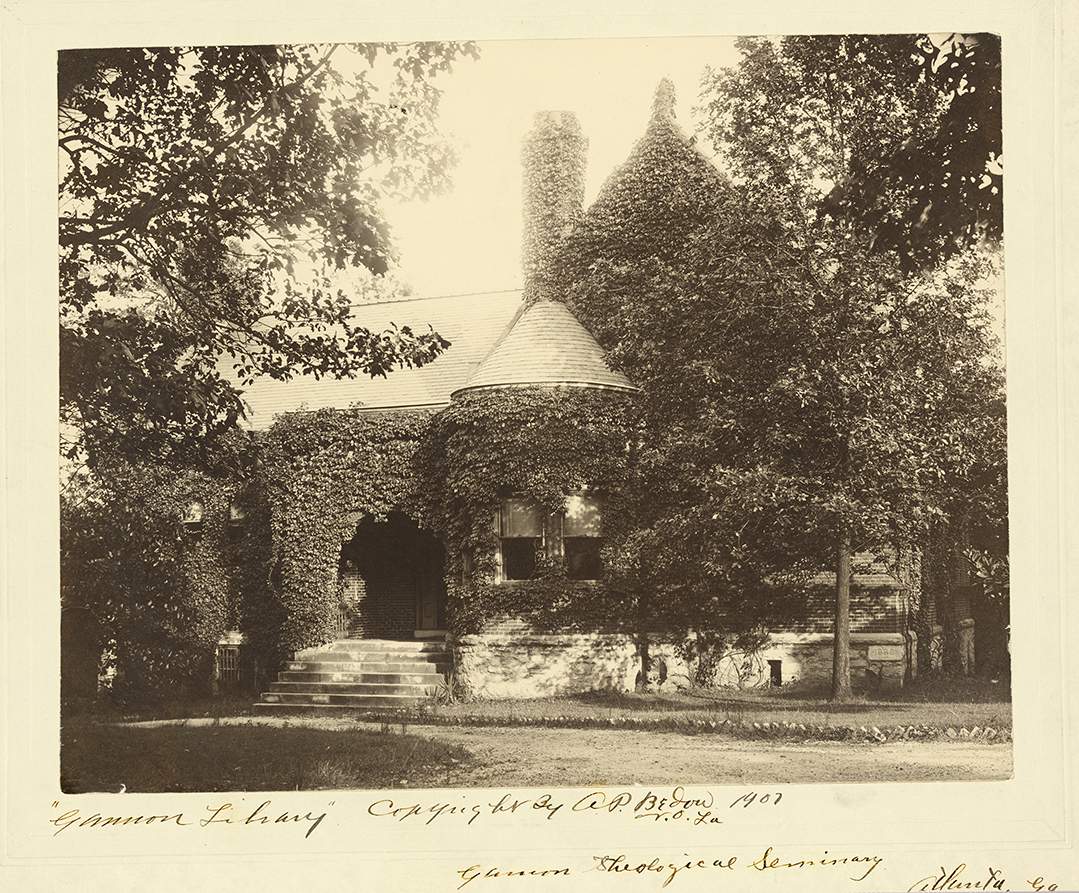

| Gammon Theological Seminary library, 1907 |

This vision of Protestant religious identity and seminary education came to its fullest flowering during what Miller calls the “religious revival” after the Second World War. He suggests that the increasing enrollments and generally healthy levels of participation in both seminaries and churches may have had demographic and social causes rather than strictly religious ones, but they were experienced by mainliners at the time as the fruition of their longstanding hopes to furnish the nation with moral guidance. The wide name recognition of theologians like Niebuhr and Tillich spoke to a hunger in the broader society for the expertise that religious specialists were thought to provide, and seminaries were the places where such experts gained their qualifications.

In Miller’s telling, it all fell apart beginning in the 1960s. The slowing of economic growth in the larger society, including the stagflation of the 1970s, the recession of the ’80s, and the more recent recession of 2008, led to an endless series of financial crises for seminaries. Miller is quick to point out that these financial difficulties have been, in fact, the normal state of affairs for most of the history of American theological education, with the postwar boom as the true anomaly. But the ’50s and early ’60s are recent enough to be remembered as a golden age by many in both church and seminary.

Economic difficulties have been accompanied by social changes that have reduced the role of seminaries in American religion, and of the mainline churches (and perhaps now also of religion in general) in American society. The rise of evangelicalism in the last few decades of the 20th century challenged the supremacy of the mainline (or, in Miller’s term, “Mainstream”) churches within American Protestantism. These more conservative congregations, descendants mostly of the “fundamentalism” of the early 20th century, have developed their own large and flourishing institutions of theological learning, although they continue to be wracked by conflict over the proper boundaries of evangelical faith. Evangelical institutions are often more innovative in the adoption of technology or programs of distance learning than mainline institutions, in part because as a whole they are “comparatively young institutions with a small capital base” and “fewer expensive investments in buildings and land” (Plurality, 338). The diversity of the American theological education scene has further been enhanced by the integration of Catholic institutions, after Vatican II, into the Association of Theological Schools, and their adoption of programs that largely match those of Protestant institutions, though significant differences remain. Furthermore, Miller reports a trend among mainliners as well as evangelicals toward other, non-seminary ways of training clergy. At the same time, the former dominance of seminaries in the world of religious scholarship has been broken by the emergence of secular religion departments, which now produce the vast majority of scholarship on religious subjects, spurred on by a more urgent “publish or perish” schedule for new faculty than is common in seminaries.

The collapse of consensus

It’s easy to see, then, why Miller would name his third volume Piety and Plurality. The “professional model” of ministry that dominated the second volume has, in his view, collapsed as a unified model for seminary education. Miller doesn’t think that any real successor has emerged. I find this part of his argument a bit puzzling, because he spends some time on what he calls a “new professional model.” The new model differs from the old one in its focus on the formation of people who “think theologically” rather than simply carrying out various professional tasks. This new model emerged in part as the result of a debate in the 1980s about the nature of theological education and just what makes it different from other forms of graduate/ professional education. I don’t find that Miller spends enough time on just what distinguishes this “new model” from the old one, but he clearly doesn’t believe that it has the widespread acceptance that the old one did. One reason for this may be the greater diversity of the schools that are members of the Association of Theological Schools. Catholic and fundamentalist institutions, which were formerly seen as radically different from mainline seminaries, are now included under the same broad umbrella.

The plurality Miller finds in the past 50 years is theological as well as institutional, even within mainline seminaries themselves. Among mainliners, the “religious revival” of the postwar era was dominated by theological consensus that centered on Emil Brunner, the Niebuhr brothers, and later Karl Barth, but this consensus was soon shattered by the emergence of more radical thinkers like Tillich, Bultmann, and Bonhoeffer.

But even more influential in the development of theological “plurality,” according to Miller, was what he calls the “Rights Revolution” that began with the African-American civil rights movement and continued through Hispanic liberation theology and feminism to its most recent embodiment in the gay rights movement. These movements all generated theological work that challenged the status quo, arguing that the perspective of underprivileged people needed to be taken into account as a source for theology. This, as Miller sees it, furthered the trend toward fragmentation and pluralism within mainline theology.

Miller’s second and third volumes, then, chart the rise and decline of mainline Protestantism through the story of the theological institutions that train mainline clergy. It is, in many ways, a classic tragedy in which the hero, the “professional model,” achieves great things but is in the end undone by its own hubris. The hubris of the “professional model” consisted of ignoring or downplaying the fundamental, irreducible reality of seminary education — that it is designed to train ministers to serve in particular churches with particular traditions and theological commitments. Miller has warm words for the professional model, but he clearly sees its bypassing of theological particularity as finally inadequate.

Back to the beginning

But to understand both why the post–Civil War professional model seemed so appealing and why it ultimately came apart, we must understand what it replaced. And that is the job of Miller’s fascinating first volume, Piety and Intellect, which traces the story from the beginnings of American seminaries in the early 19th century to the Civil War.

Whereas the second and third volumes describe a world of theological education that is recognizable to contemporary readers, the first volume takes us to a more alien world. Of course there are important continuities. Indeed, Miller comments that some of the basic structures of the American Protestant seminary, such as the three-year program, appear to be imitations of what he considers the first true American seminary, Andover. But there are many sharp differences as well. The early seminary faculty often did not specialize — some seminaries had only one faculty member, and even where there were several they often taught more or less the same courses. The first field to be sharply specialized was biblical studies, and the early biblical scholars were largely self-taught. Moses Stuart, professor of Bible at Andover and father of American biblical scholarship, taught himself Hebrew on the job while also acquainting himself with the growing body of technical scholarship being produced in Germany.

|

| Andover Theological Seminary, 1891 |

The chief goal of the early seminaries, as defined by Miller, was to defend a particular theological perspective valued by a particular community — a denomination or even a faction within a particular denomination. For instance, Andover was founded by adherents of Jonathan Edwards’s theology in response to what they regarded as the unorthodoxy of their fellow Congregationalists at Harvard, and to preserve this theological commitment, Andover had a special doctrinal statement, laying out Edwardsean theology in great detail, to which all faculty were expected to subscribe. Princeton Seminary was also founded to preserve a particular theological perspective — Old School Presbyterianism — which it did by inviting faculty and presidents from Scotland to create a colony of Scottish theology in the United States. Most seminaries, however, were not as successful as Princeton. Most in the antebellum period were tiny institutions with perhaps three faculty members.

A constant refrain throughout Miller’s three volumes is the phrase “too many seminaries.” As Miller sees it, this reflects the broader problem of the fragmentation of 19th-century American Protestantism. Because denominations, in this pre-ecumenical era, made strong and conflicting truth claims and competed against each other actively, they duplicated their efforts and created many weak churches and seminaries rather than a few stronger ones.

It’s important to remember that Miller’s three-volume history has appeared over the course of a quarter century, and other scholarship has been emerging during this time as well. Miller’s first volume, published in 1990, predated by two years Roger Finke and Rodney Stark’s groundbreaking The Churching of America, which argued the opposite thesis about religious competition. In this work and in their more general study, Acts of Faith, in 2000, Finke and Stark popularized the idea that competition was good for American religion, resulting in a religious “market” in which every kind of religious inclination had a corresponding church. So Miller sees the 1804 Plan of Union between the Congregationalists and Presbyterians as a praiseworthy development, which promised to eliminate competition between the two denominations but which was unfortunately abandoned. Taking the contrary position, Finke and Stark describe it as a serious mistake that left both denominations weaker. Given how important the “too many seminaries” theme is to Miller’s narrative, I wish he had found a way to engage with Finke and Stark’s thesis more explicitly (though he does mention their broad theory of “rational choice” favorably in the second volume).

In the antebellum period, then, the primary concern of theological education was to preserve and defend the theology of a particular community. The other half of Miller’s title, “Intellect,” refers to what Miller describes as the “English” tradition of gentlemanly classical education. Miller argues that this is what early American universities such as Harvard and Yale provided. While these universities did have professors of “divinity” before the formation of Andover in 1807, Miller claims that prospective ministerial students received only the most rudimentary training in theology. For the most part, clergy until the 19th century had been educated as other young gentlemen were educated, through the study (mostly by rote) of the Latin and Greek classics. The early seminaries assumed this classical education as a basis, although this sometimes meant that they had to provide remedial college classes for seminarians.

Miller estimates that only a minority of clergy in the early 19th century had even a college education, with a seminary education rarer yet. These graduates of the early seminaries were elites, usually pastors of large urban churches, college professors or presidents, or seminary professors themselves. Most clergy still received their education through a course of readings, or in rural areas and the more populist traditions simply through a divine call supplemented by whatever reading they had time for.

Miller avoids the easy trope of “anti-intellectualism,” arguing that pretty much everyone in the 19th-century American theological scene valued education. The question was whether education was a prerequisite for ordination (which Baptists and some Methodists denied) and whether that education should be received through a liberal arts college, a seminary, or an informal course of readings. Alexander Campbell, for instance, founder of the Disciples of Christ, was a passionate advocate of public schools and of college education, but highly skeptical about the value of technical theological education.

A similar attitude was common among Methodists, which, Miller argues, is why they founded seminaries late and then generally as part of universities. Eventually these Methodist divinity schools, along with the flourishing divinity schools that developed at Harvard and Yale, would become the intellectual powerhouses of 20th-century theological education, with the resources and infrastructure that most freestanding seminaries could never match.

The world of theological education painted by Miller’s first volume, then, differs from that of the other two in being far more concerned both with theological particularity and with training resident intellectuals who would raise the cultural tone of a community. Only after the Civil War did technical professional education become the primary purpose of a seminary, and even then it faced competition from “training colleges,” particularly the Bible institutes that sprang up in the wake of revivalist movements led by Dwight L. Moody and other evangelists. After the fundamentalist-modernist split of the early 20th century, these institutes were seen as fiery rivals to the more respectable seminaries, though many of them eventually became colleges or seminaries themselves. Yet even the mainline denominations had training institutes, many of them founded specifically to prepare women for the mission field, Christian education, and other particular fields. The professional model has never been the only way that American Protestants have envisioned theological education.

This summary of Miller’s work has, by necessity, left much out, particularly in the very meaty second volume. For instance, I might have mentioned Miller’s discussion of the persistent efforts of seminaries to integrate students’ ministerial activities with their education, most successful in the specific case of clinical pastoral education. Or his fascinating discussion of African American higher education and the way white benefactors shaped (and perhaps distorted) it by contributing to “manual labor” institutes such as Tuskegee rather than seminaries and liberal arts colleges. Or his even-handed account of the fundamentalist-modernist controversy. In the third volume, his moving and fair-minded account of the bitter conflicts within two denominations, the Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod and the Southern Baptist Convention, is especially notable. The footnote in the chapter on the Southern Baptists in which Miller lays out his own perspectives on the conflict, and his broader theological perspective, is one of the most moving passages that I have read in any theological work.

Unfortunately, the series suffers from a high number of typos, which I suspect is the result of the author’s need to get this magnum opus to press. On the other hand, the three volumes also contain extremely pithy and memorable writing, and the work as a whole is shot through with dry wit and a humane but fiercely critical wisdom honed by Miller’s own involvement in some of the most turbulent events of late–20th-century seminary education.

In the end, Miller leaves us with no pat answers, only the confidence that the future will bring yet more surprises. If there is one lesson to be taken from the series, however, I think it is that the norms most people in theological education have learned to take for granted are historically contingent and that theological education can exist without them. The fundamental tension, however, between intellectual exploration, practical training, and doctrinal faithfulness has been present from the beginning, as has the persistent worry that intellectual activity might compromise the integrity of the faith. These tensions are manifest in the strife that led to the formation of Andover in 1807, in the internecine conflict among Lutherans and Baptists in the late 20th century, and in the deep concern of contemporary mainline seminaries for multiculturalism and social justice as key commitments of Christian faith. There are no easy answers, but Miller has provided us with an excellent starting point for finding the hard answers.

Photos from the Library of Congress