Katarina Schuth, holder of the Endowed Chair for the Social Scientific Study of Religion at the Saint Paul Seminary School of Divinity in Minnesota, draws on decades of experience with Catholic theological education for this well-researched and succinct survey of the programs offered by the 39 institutions training priests in the United States. The book is divided into four parts: an introductory discussion of the effect of Vatican II on American seminary education, two chapters on organization and personnel, three chapters on students and their formation, and a concluding section consisting of Schuth’s own conclusion as well as five reflections on American seminary education by other authors.

The introductory chapter on Vatican II sets the stage for the entire book. While Schuth’s tone is carefully objective, underneath the barrage of statistics and surveys lies a broad narrative: In recent decades, the influence of Vatican II on theological education has waned while the influence of John Paul II’s pontificate has grown.

Schuth traces the changes over the five editions of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ “Program of Priestly Formation” (PPF), which appeared in 1971, 1976, 1981, 1992, and 2005. While the first three editions are full of citations of Vatican II’s document on priestly formation, Optatam Totius, in the last two editions that document is largely eclipsed by John Paul’s Pastores Dabo Vobis. Schuth points out that the Catholic bishops, seminary administrators, and faculty who currently serve are less likely than in past decades to have living memory of Vatican II. Throughout the book, she returns to the theme of the “eclipse of Vatican II” frequently, though generally in brief and understated ways.

Thomas Walters, professor emeritus of religious education at Saint Meinrad Seminary, addresses the same theme in his reflection on “Generational Differences” in part 4 of the book, describing the gap between older faculty and administrators on the one hand, and students and younger faculty from more recent generations on the other. While the older folks look back on a strong communal formation in traditional Catholic culture and seek to appropriate the faith in a more personal way, younger people look back on a formation characterized by “balloons and butterflies” and consequently seek more solid doctrinal instruction and a firmer grasp of orthodoxy. The evangelistic emphasis of John Paul II, in which the priest is a “bridge” between people and God, is appealing to these younger seminarians and scholars.

Structurally, the revival of what Schuth calls the “cultic” model of the priesthood expresses itself in greater segregation of seminarians from the laity. In the years after Vatican II, academic programs and programs of formation for lay ministers multiplied, and they continue to be important, yet many seminaries have disconnected the lay programs from the programs of priestly formation. Furthermore, the 2005 PPF requires “formation advising” and spiritual direction to be handled by priests, and encourages seminaries to employ exclusively priests to teach “major theological disciplines” and oversee field education (page 67). This seriously limits the roles open to female religious and to laypeople of both sexes.

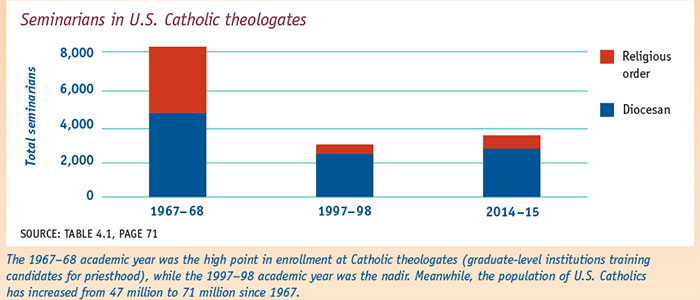

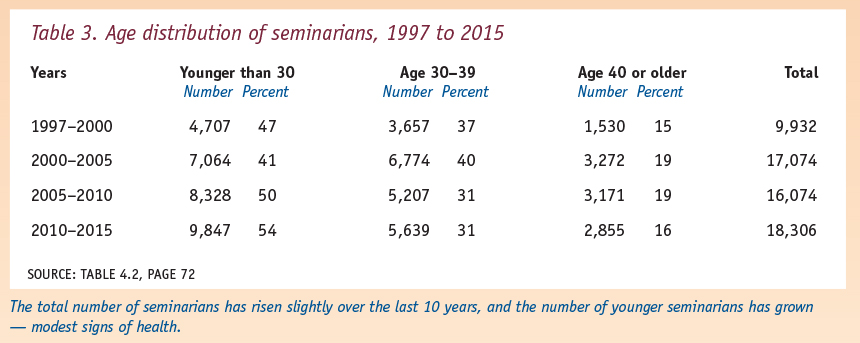

|

At the same time, the growing cultural diversity of American Catholicism has been reflected to some extent in the seminaries. Since 1994–5, when data on the ethnic composition of seminarians was first collected, the percentage of non-Hispanic white students has dropped and the percentage of Hispanics has grown, but by proportions that fall far short of the corresponding changes in the American Catholic population as a whole. In addition, about 23 percent of seminarians come from outside the United States, and many face serious cultural adjustment in dealing with U.S. congregations, including difficulties in adapting to the lower levels of deference afforded to authority figures in North America in comparison to the countries from which they come.

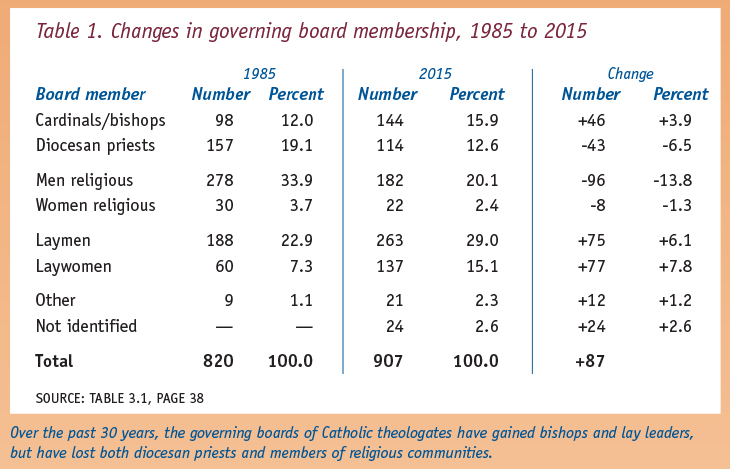

|

| Seminary Formation: Recent History - Current Circumstances - New Directions, by Katarina Schuth, O.S.F. (Liturgical Press, 2016, 212 pp., $25). |

Schuth notes that young priests, who have not had the experience of studying alongside women and laymen, may have difficulties relating to their congregations. This has led to especially conflicts with lay ministers, whose numbers have grown and who reflect the ethnic composition of American Catholicism much more closely than seminarians do (particularly in the number of Hispanics). In contrast to new priests, lay ministers often begin their ministry at a mature age and may expect to be treated as colleagues — an expectation that younger priests are often unwilling to meet (page 81).

Recent decades have also seen a shift in emphasis on how Scripture should be preached and interpreted. After Vatican II, the first few versions of the “Program for Priestly Formation” emphasized historical and textual criticism, which Catholic seminaries embraced. But recent versions of the formation document have questioned such critical methods of scripture interpretation while encouraging more traditional, theological methods. Barbara Reid, one of the authors in Part IV, worries that this contributes to younger seminarians’ tendency to substitute pious “talks” for serious exegesis.

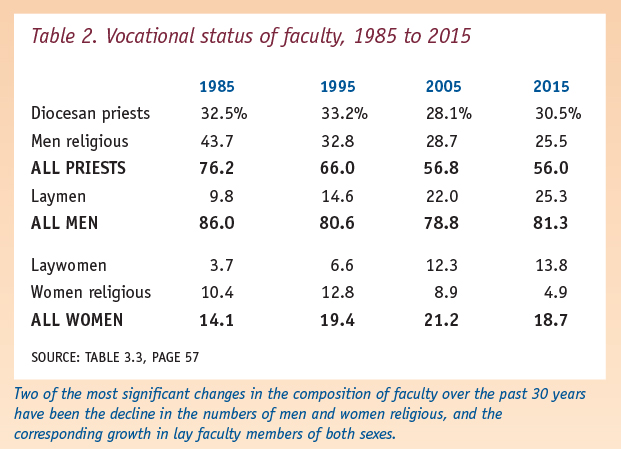

|

An overarching theme present throughout this book is the relatively new emphasis on “human formation” in seminary education, discussed by Schuth in the main text and also by Leon Hutton, former director of human formation at St. John’s Seminary in California, on pages 143–53. The concept of “human formation” was introduced by Pope John Paul II in Pastores Dabo Vobis, but it has also been heavily shaped by the experience of the Catholic Church in dealing with the sexual abuse crisis of the early 2000s. “Human formation” concerns itself with the integration of all aspects of a priest’s development, including a healthy psychological attitude to his own sexuality. Human formation programs spend a good deal of time helping seminarians think about the vocation of celibacy and develop spiritual and psychological disciplines that will help them lead the celibate life as a joyful gift of love.

As Hutton points out, John Paul’s understanding of the need for the priest to be a “bridge rather than an obstacle” is at the heart of human formation. Thus, the renewed focus on a “cultic” model of the priesthood is not simply a repetition of traditional attitudes but is shaped by an evangelistic vision of the church’s ministry and an emphasis on the integrated humanity of the priest. At the same time, the frequent reports one hears of “rigid” or “legalistic” younger priests indicate that perhaps this goal remains more of an ideal than a reality.

|

Ronald Rolheiser’s reflection on “a spirituality of ecclesial leadership” (pages 122–31) and Peter Vaccari’s on “a culture of encounter” (pages 164–73) also have a great deal to say about “human formation.” Rolheiser is concerned with what he sees as an overemphasis (particularly in the 2008 Vatican visitation of U.S. seminaries) on the preservation of orthodoxy, at the expense, for instance, of a concern with exposing students to the arts and other culturally broadening experiences. He worries about overprotection of seminarians, while also recognizing that their earnest faith needs to be encouraged rather than squelched. He further notes a lack of interest in ecumenism among many students, while commending seminaries in recent decades for challenging seminarians with regard to social justice.

Vaccari provides a helpful survey of the theme of “encounter” in the ministry of the last three popes, with particular emphasis on Francis’ Evangelii Gaudium. The reflections by Rolheiser and Vaccari open and close the section of the book not authored by Schuth herself, and I found them particularly helpful in surveying the concerns found throughout the rest of the volume.

A list of seminaries

For Appendix 2-A of Seminary Formation, Schuth created a list of all U.S. Catholic seminaries organized by structure. See the list at www.intrust.org/schuth.