Theological education is not just about forming students intellectually — it is about forming students spiritually as well. At least that is what most people probably think. The widespread assumption is that while attending seminary, students’ knowledge will increase and their spiritual lives and practices will deepen and grow.

However, it’s fair to ask whether this assumption is actually true — not just among traditional students, but especially among the increasingly part-time students who are participating in new kinds of education (like online courses and extension sites). That’s why the Association of Theological Schools (ATS) has been working alongside seminaries to measure the spiritual formation of their students in the variety of settings in which they study.

The ATS Graduating Student Questionnaire (GSQ) has several questions that explore the impact theological studies have on students’ spiritual lives. Below we’ll explore four data points related to the effectiveness of theological education to facilitate the following: (1) the ability to live one’s faith in daily life, (2) the ability to pray, (2) strength of spiritual life, and (4) trust in God.

INSIGHTS

In 2015–16, almost 6,300 students at 183 schools completed a Graduating Student Questionnaire. Data from 2016 was analyzed and then compared to similar data from the last eight years.

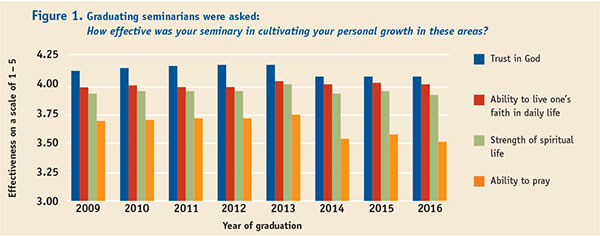

The questionnaire asks graduating students to rate the effectiveness of their school in facilitating 15 areas of personal growth, from “concern about social justice” to “enthusiasm for learning” to “self-discipline and focus.” Figure 1 shows the numerical values assigned to the four items related to spiritual formation, on a scale of 1 to 5. Trust in God is ranked highest (in the 6th position) relative to all 15 areas of effectiveness, followed by ability to live one’s faith in daily life (9th), strength of spiritual life (13th), and ability to pray (15th). The ability to pray has been last on the list of 15 for at least the last eight years.

Note a sharp dip in the data from 2013 to 2014, which reflects changes that took place in the questionnaire. Prior to 2014, the GSQ asked students to measure their own personal growth in each area from much weaker to much stronger. In 2014, the question changed to focus on student perceptions of the effectiveness of their seminary in facilitating growth in each area. The increased clarity in the question simply highlighted the challenge theological schools are having in facilitating spiritual growth in their students.

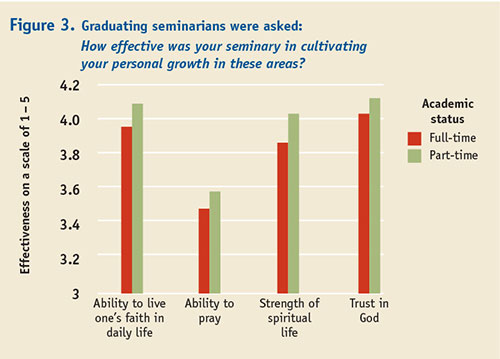

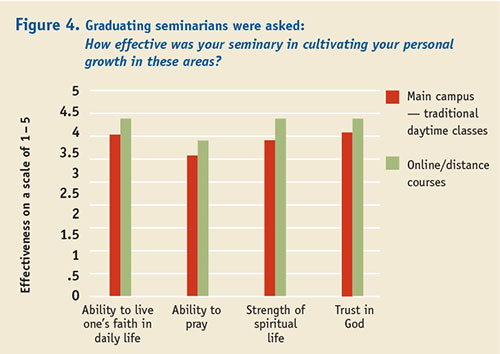

Which cohorts of students have perceived theological education to be more effective in facilitating spiritual growth over the last eight years? And which have perceived it to be less effective? On a scale of 1 (“not at all effective”) to 5 (“highly effective”), graduating seminarians generally rate all areas of personal growth between 3.5 and 4.5. However, some groups do rate items related to spiritual formation either higher or lower than others:

Seminary was more effective in facilitating spiritual growth:

-

Catholic students

-

Black (non-Hispanic) students

-

Professional master’s students

-

Part-time students

-

Online students

-

Older students

Seminary was less effective in facilitating spiritual growth:

-

Mainline students

-

White (non-Hispanic) students

-

Academic master’s students

-

Full-time students

-

Traditional on-campus students

-

Younger students

These findings have remained remarkably steady over the last 8 years.

ANALYSIS

Some of the differences in the ratings can be attributed to various emphases within degrees and approaches to theological education. Catholic theological education, especially that segment focused on candidates for the priesthood, is more fundamentally formational than other forms of theological education. Mainline theological education is more likely to include divinity schools and research universities that prioritize intellectual formation. Historically black seminaries are more likely to focus on forming students personally and spiritually within a specific cultural context. Academic master’s programs (like those leading to a master of theological studies) tend to focus more on intellectual formation while professional master’s programs (like those leading to a master of Christian education or a M.A. in youth ministry) are more likely to have more of a spiritual formation emphasis.

It is perhaps surprising to note, however, that students graduating with the standard ministry preparation degree, the master of divinity (M.Div.), rate these four areas of spiritual formation as somewhat less effective than do their colleagues graduating with professional M.A. or doctor of ministry (D.Min.) degrees. However, with the exception of ability to pray, M.Div. students still rate the other three areas as 4 (“effective”) on the 1–5 scale. This may be due to differences in the degree programs, but it may also be due to the makeup of students in each degree. D.Min. and professional master’s students tend to be older, and older students tend to rate their theological schools as more effective in spiritual formation.

It is also surprising to note that part-time and online students rate theological schools as more effective in facilitating spiritual formation.

This may be due to the fact that many online and part-time students are older and enrolled in professional master’s degree programs — both criteria that correlate with higher ratings in areas of spiritual formation. However, it raises interesting questions about how spiritual formation takes place in theological education, or at least how students perceive it to take place. A long-standing assumption has been that spiritual formation is best when it occurs face to face within a more intentional communal setting. The data raises questions about whether or not this assumption is accurate.

It may be that part-time and online students have different expectations about the spiritual formation that should take place in seminary. And, it may be that the way theological schools do spiritual formation is actually more effective when students are also embedded in other faith communities while they attend seminary.

Why do students consider theological education more effective in spiritual formation as they grow older? Is it because of the generational gap between younger students and the professors and chaplains who facilitate spiritual formation programs in seminaries? Does it have to do with stages of spiritual development? Young people are often in a time of tremendous growth and discovery in their lives. Do they have higher expectations for spiritual growth during seminary than older students who have reached a more stable spiritual path — or perhaps who have plateaued and are attending seminary precisely to promote spiritual growth? Do younger people crave a more experiential spirituality that is not fully satisfied by intellectual and reflective approaches to spiritual formation?

What does that data look like in your own institution? And can it help answer some of these questions?

NEXT STEPS

The definition of spiritual growth and maturity varies greatly from context to context. When using data to determine the effectiveness of your institution in facilitating spiritual growth in your students, the first question to ask is whether or not we are using the right categories to define spiritual growth. Would questions about empathy for the poor and oppressed, daily Bible reading, or doing acts of service provide additional insight into the spiritual formation of your students? Is there a reason they are not connecting with the language of the Graduating Student Questionnaire? Or is this an accurate reflection of their perceptions about spiritual growth in seminary?

Start by getting a clear definition of what spiritual growth might look like at your institution. Look at the mission of your institution, the outcomes for your degree programs, the learning objectives in your courses. What is the language of formation used by your institution?

Once you have a good definition of spiritual formation and have determined the right questions to consider, what differences do you see among your own students? We’ve seen that the data from the GSQ reflects ecclesial, racial/ethnic, and generational differences in experiences of spiritual formation. It may also reflect ways that the culture of theological education either connects or does not connect with the spiritual life of various students. Who within your student body is experiencing spiritual formation as particularly effective? Where are the gaps?

Once gaps are identified, be cautious about moving too quickly towards programming. Spiritual formation is deeply tied to students’ identities, backgrounds, and experiences. Before changing current programs or creating new ones, it would be wise to conduct further research with current students and alumni to better understand their definitions and practices of spiritual formation. It may be that you already offer great programming, but students are not taking advantage of it for a variety of reasons. Perhaps the timing doesn’t work, or spiritual formation is framed in language that does not connect with certain demographic groups. Or, perhaps more emphasis needs to be placed on teaching the value of the particular approaches your institution focuses on.

It may be, however, that the spiritual formation offered by your school really is not as effective as you would hope. If that is the case, do you as an institution need to explore new (or rediscover older) language and practices for worship, prayer, and formation?

Daniel O. Aleshire, executive director of the Association of Theological Schools, has suggested that the future of theological education may be more formational. Within an increasingly diverse society that practices faith in increasingly diverse ways, personal and spiritual formation become ever more central to theological education. Such diversity, however, also requires more intentionality about our approaches to formation and a better understanding of the ways students are shaped spiritually.