|

| Columbia Theological Seminary |

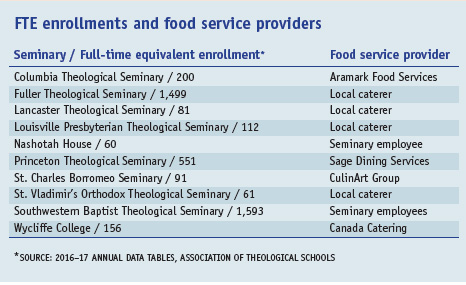

For theological schools in the United States and Canada, maintaining on-campus food service has become almost impossible without subsidies. Declining enrollment and increasing numbers of distance education and off-campus students are making the economics of providing food increasingly unsustainable. But everyone agrees that shared meals build community.

How are North American theological schools addressing this challenge? Interviews with administrators and business officers at 10 seminaries reveal that most of them outsource the food service to a local caterer or larger, national vendor. Even so, it’s difficult to break even, and most seminaries subsidize the food service companies that provide the meals. The schools that require residential students to purchase a fixed meal plan are generally more successful at breaking even than those that do not.

Wycliffe College, an Anglican seminary in Toronto, places a high value on giving students from its five degree programs opportunities to eat together, says Paul Patterson, director of business operations. Students may purchase lunch six days a week at the subsidized rate of just three Canadian dollars (US $2.33). Dinner after Wednesday night chapel is free for students, faculty, and staff, and the most popular M.Div. courses are scheduled after the Wednesday night dinner to encourage strong attendance at the weekly worship and meal.

|

"The community-building aspect is really important to us. We have always resisted raising the prices for lunches and dinners because we believe it's important for students to eat together as often as possible"

-- Paul Patterson, Wycliffe College |

Wycliffe has a head count of 241 students and an FTE enrollment of 156, according to the latest Association of Theological Schools (ATS) figures. The approximately 70 residential students are required to purchase a meal plan that offers breakfast and dinner five days a week. Students not on the meal plan, along with faculty and staff, can purchase dinners for $10.

A local catering company has provided all food services for 25 years, but the seminary “heavily subsidizes” the lunches and Wednesday dinners, says Patterson. No food is offered during the summer term.

“There haven’t been many connections between students in the different degree programs,” says Patterson. He says that the daily lunches are one way to help students get to know one another and to give them space for discussion. “The community-building aspect is really important to us. We have always resisted raising the prices for lunches and dinners because we believe it’s important for students to eat together as often as possible.”

Columbia Theological Seminary in Georgia uses Aramark, one of the largest food service providers for educational institutions. Aramark offers Columbia seminarians three meals a day, Monday through Friday. “People who live in rooms that do not have cooking facilities are required to be on the board plan,” says Marty Sadler, vice president for business and finance. Even then, the seminary “heavily subsidizes its food services — in the low six figures,” he says.

“The debate is whether a small standalone school should provide food service and what it should look like,” says Sadler. “I don’t think anyone is going to make any money on it. I don’t even think anyone is going to break even on it.”

Princeton Theological Seminary in New Jersey, a freestanding seminary completely separate from Princeton University with more than 500 students, recently switched from Aramark to Sage Dining Services, which offers student plans with 10, 15, or 19 weekly meals. “We require a meal plan for those living in single student housing,” says Kurt Gabbard, vice president for operations. “This is a significant factor in making it more economical to run the food service.” He notes that catering campus events is another component in making the finances work, but even so, a subsidy is required. “We try to break even, but we don’t.”

Gabbard says that sharing meals is an important part of the process of forming leaders for the church. “In fact, one of the main reasons we chose Sage is that they share this philosophy about food and want to be partners with us in carrying it out. The seminary’s food service is an important part of fostering a sense of community.” Gabbard worked at another seminary before moving to Princeton. He says that after numerous complaints from students, that seminary dropped the meal plan requirement for those living in single-student housing. “Within a few years, the dinner service was eliminated due to low participation. Only one or two people a night were using it. It’s very hard to break even under those circumstances. We were subsidizing the food service by a significant amount at the time.”

Lancaster Theological Seminary, a United Church of Christ seminary in Pennsylvania, has found a way to make food services work in their context. A local caterer has the exclusive right to use the seminary’s stunning refectory for special events, like weddings. That caterer also sells lunch in the refectory five days a week. “When I started here, we had a staff person working part-time on food service and providing lunch,” says David Mellott, vice president for academic affairs and dean. “We didn’t have enough volume to be able to do food service sufficiently. We ended up wasting a lot of food because you couldn’t guarantee who would be in and who wouldn’t.”

They decided that they could no longer afford to operate a lunch program, so seminary leaders sought a caterer or restaurant owner to use the kitchen for catered events. “They would rent the kitchen from us and provide lunch on a regular basis for the campus,” says Mellott.

|

"The company has done a great job. They are well-known restaurant operators in the city....If they book a wedding or event, we also get a percentage of the booking fee."

-- David Mellott, Lancaster Theological Seminary |

Gypsy Kitchen, a local firm, agreed to provide the services. “The company has done a great job,” he says. “They are well-known restaurant operators in the city. They do catering for the seminary and serve lunch five days a week.” He adds that Gypsy Kitchen also runs a “pop-up restaurant” on Friday and Saturday nights that is open to the public. “We have people coming to the campus to eat,” says Mellott. “It’s been a great boon for the seminary because it draws people to campus. The food quality is high and not too expensive.”

And the big shock: “We make some money off of it. We have some rent that comes from it. If they book a wedding or event, we also get a percentage of the booking fee,” says Mellott.

Mellott is a strong proponent of communal meals. “Having the experience of sitting down and eating together at the same table is quite significant. While there’s a financial dimension to all of this, we have to pay attention to the formation part of the seminary training,” he says. “While maybe we can’t eat together all of the time, we can have moments where we do share meals together.”

Fuller Theological Seminary in California outsources its food services to Simply Gourmet Plus, a local caterer. It does not require a meal plan and all meals are served à la carte. The cafeteria is open for three meals a day during the academic year and two meals a day during summer and vacation periods. Gerardo Garibay, the owner of Simply Gourmet Plus, says he serves about 400 meals daily to 150 students and staff. His company uses the seminary’s kitchen and facilities but does not receive a subsidy from the seminary.

Fuller has more than 1,400 students from 90 countries and 110 denominations. “We have student housing, and most of our students have families,” says Jeanne Handojo, director of auxiliary services. “Not many go to the cafeteria, because they go home and eat.”

Across the country in Pennsylvania, St. Charles Borromeo Seminary uses the CulinArt Group, a national company, to provide on-campus meals.

“Right now, we have the largest enrollment we’ve had since 2004,” says Stephen Dolan Jr., the seminary’s chief financial officer. “We provide three meals a day, seven days a week, throughout the whole school year. We charge all resident seminarians the same tuition, room and board, and fees. The seminarians do not have an option on meal plans,” he says.

|

The New Legacy Reentry Corps, a Louisville nonprofit that teaches job skills to ex-offenders, provides the dining service at Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary. At left, Chris Hamilton, executive chef for the seminary's dining services. At right, Courtney Phelps, the organization's government affairs director.

Credit: Chris Wooton |

Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary used to run a dining service internally, says Pat Cecil, vice president and chief operating officer, but it required a “significant subsidy” every year. So in 2014, the seminary decided to contract food services to an external caterer. Unfortunately, that vendor went out of business in January 2017, leaving the seminary without food service for about five months. The time without on-campus food helped Cecil and the seminary’s leadership realize how important communal meals were to student life.

In February 2017, Louisville Seminary hosted a conference catered by the New Legacy Reentry Corps, a local nonprofit. “Basically, it’s a faith-based program that takes ex-offenders of non-violent and non-sexual crimes and reintegrates them into the workforce and teaches them job skills,” Cecil says. “They were ready to start a culinary arts training program.”

Once they began a conversation with New Legacy, “it was obvious that they could benefit and tie into the mission of our seminary very well,” he adds. “We provide them our full-service kitchen and they provide the dining services, breakfast and lunch, at the seminary. But they also use it as part of their training program to teach culinary arts skills to their clients,” he says.

The seminary does not require students to purchase a food plan, and New Legacy assumes full responsibility for any profit or loss. However, “By having New Legacy provide nourishment to our campus community, we, in turn, are nourishing the spirit of restorative justice and giving formerly incarcerated individuals a chance to start their lives over on a positive and productive note,” Cecil says.

With an FTE enrollment of 1,593, Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Texas has the largest student body of the seminaries surveyed for this article. Such volume enables it to manage its own food service with its own employees. “Our dining services are composed of a café, a full-sized cafeteria, and a catering service,” says Charles Patrick, vice president for strategic initiatives and communications. “We serve about 160,000 guests a year. We have 70 dining services employees; 60 of those are students who work part time.”

The seminary does not require students to purchase a food plan, and all cafeteria items are sold à la carte. Patrick says that food services are managed at a break-even margin and subsidized by the seminary when needed.

On the other hand, Nashotah House, an Episcopal seminary located in Wisconsin, has the lowest enrollment of the seminaries surveyed for this article. Yet it manages a successful food service with one full-time employee and part-time student help. The food service offers breakfast and lunch five days a week, and all students are required to purchase the 10-meal plan. Faculty members are encouraged to join students for breakfast and lunch and are not required to pay for their meals.

“It’s a Benedictine model; it’s considered part of student formation,” says Phil Cunningham, associate dean for administration. “We start the day with chapel, and then breakfast and classes, and then lunch together. Eating together, rather than grabbing something when you feel like it, is an essential part of the day.”

Cunningham adds that eating together is “very much part of what we do.” “Generally, a lot of discussions and further learning take place at meals. I don’t think it would work if we didn’t have meals together. It would be just a ‘show up and take classes and go home’ type of environment,” he says.

“Right now, our enrollment is down a little. When we have enough students, we break even and maybe make a little bit of money. If we don’t have enough students, we lose a little. It’s never too dramatic; maybe make $10,000 or lose $10,000,” says Cunningham.

St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary in New York trains priests for all Eastern and Oriental Orthodox traditions and charges a required board fee for all single, residential students. About half of the seminary’s full-time students are single. Married students and faculty pay by the meal. The seminary uses a local caterer, who prepares 40 or 50 meals three times daily except Sunday.

Orthodox Christians practice a strict regimen of fasting from meat and dairy products on Wednesdays and Fridays and daily during Advent, Lent, and holy days. That makes food services a real challenge for the caterer, and the most frequent complaint is “too much pasta,” says Father Chad Hatfield, St. Vladimir’s president. “Food service — what students eat — is kind of at the heart of their happiness.”

Ted Bazil, senior adviser for systems and operations at St. Vladimir’s, says that students are assigned to community service as part of their formation. “So they are also doing dish crew, set-up, and clean-up,” he says. “That’s a big part of our food service since the caterer is essentially a one-man operation. If we had to hire staff to do that, it would add a lot to the cost,” says Bazil.

It’s clear that no one-size-fits-all food arrangement works for every campus. A small seminary makes it work with one full-time employee, while some large seminaries use providers who still require a subsidy to break even. Pat Cecil from Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary sums up the dilemma. “Dining services are a challenge, but it’s a critical component of community building,” he says. “We have to be creative in finding solutions to provide that service.”