Faced with harsh realities, many theological schools find they can no longer put off tough decisions. What are these realities? While they are different for each institution, for the most part, the challenges are similar: shifting student demographics; changes in educational delivery methods; denominations that no longer have the means or inclination to support theological schools in the way they once did; a more urban, diverse, and secular culture that makes recruitment more difficult; more campus space than they need or can afford, or space that simply no longer meets their needs. And then, there is the problem of unsustainable deferred maintenance on aging buildings.

How effectively a seminary navigates these all-too-common challenges depends in large part on the ability of the school’s leadership to define, share with internal and external constituents, and fulfill a compelling institutional mission — all while maintaining or building the school’s economic vitality. Sometimes, it depends on a board’s ability to make difficult, even radical changes — like selling its campus or merging its school with another institution.

How does this work out in the real world? In Trust talked to six theological schools to find out what kinds of challenges they have been facing, what they did in response, and what role the board played in addressing these challenges. Two of the schools went through a consolidation or acquisition — one with a university and the other with a church. Another school sold its suburban campus and moved to a leased facility in the city. Another sold its suburban campus and moved to a leased facility in a different suburb. And still another sold a large building and renovated a smaller, more practical nearby building they already owned.

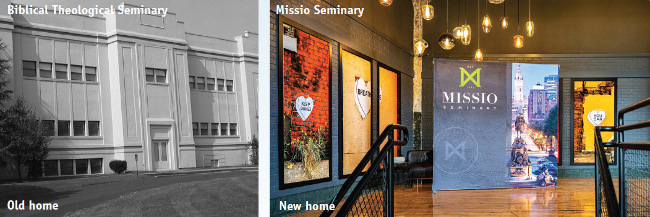

Missio Seminary - Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Biblical Theological Seminary in Hatfield, Pennsylvania, has made two major changes in the last several years. First, in October 2018, it changed its name to Missio Seminary. And then, three months later, it decided to move its main campus from suburban Hatfield to central Philadelphia, less than a mile from the Liberty Bell.

The decision to move and change the seminary’s name was tied to another fundamental change that had occurred some years earlier. Under its previous president, David Dunbar, the seminary made a significant modification to its mission, “from being more narrowly confessional Presbyterian seminary to a more missional one,” says Frank James, who was named president in 2013. James defines missional as “realizing you’re in a territory that is post-Christian — and recognizing your responsibility to engage rather than retreat.” Of the refocus, Dunbar says, “It was a DNA change. Every class [was] reconstituted for a missional perspective, only staff with that perspective [were] hired, and the board [was fully] missional as well. It was a perspective that created unity and a sense of identity.”

According to the branding expert the seminary hired — Bill Chiaravalle, coauthor of Branding for Dummies — the school’s name, “Biblical Theological Seminary,” was not in step with its new missional focus. As James recalls, Chiaravalle said the school’s “distinct difference and deep devotion to missional theology” required a new name. In 2018, they chose Missio Seminary.

The refocused mission also prompted Missio leadership to question whether the school’s suburban location was the best place to carry it out. Eventually the board decided that relocating to Philadelphia would allow the seminary to immerse itself in the culture, creativity, and community of the sixth-largest city in the United States and also increase its accessibility to current and new students.

Understanding that a big campus with classrooms and student housing is not very important to most of today’s students only made the decision to move more obvious. As board member Rebecca Campbell points out, most of the seminary’s students are urban, they don’t drive, they attend school part-time and work part-time, and all of them are used to online learning.

After an extensive search for the right location, Missio signed a lease for space on the top floor of an industrial building next to a concert venue in the heart of Philadelphia. The majority of fall 2019 classes were held in the new location, with only a few being held on the old campus in Hatfield. The president reports that he expects the move to be completed by 2020.

Church Divinity School of the Pacific - Berkeley, California

To train a “new generation of church leaders to get outside the parish gate and into the neighborhood,” Church Divinity School of the Pacific (CDSP) has been rethinking its curriculum over the past few years, says its president and dean, W. Mark Richardson. The campus of CDSP, the only Episcopal seminary on the West Coast and a founding member of Graduate Theological Union, is one block from the massive grounds of the University of California.

To train a “new generation of church leaders to get outside the parish gate and into the neighborhood,” Church Divinity School of the Pacific (CDSP) has been rethinking its curriculum over the past few years, says its president and dean, W. Mark Richardson. The campus of CDSP, the only Episcopal seminary on the West Coast and a founding member of Graduate Theological Union, is one block from the massive grounds of the University of California.

While the CDSP board and administration were thinking about how to best educate their students, they were also faced with double-edged assets — specifically, a 100,000-square-foot administration building that wasn’t being used efficiently and a 23,000-square-foot parking lot. They were also behind the curve on the technology they needed to meet the increasing demand for online education.

“We felt our assets could be better used,” says Richardson. He wanted to use the property — especially the big parking lot, coveted in crowded Berkeley, to add value to the neighborhood and also to support the mission of the school. But he was no real estate expert.

Fortunately, Richardson knew people who were. He thought of contacts at Trinity Church Wall Street, an Episcopal parish in New York City that manages a $6 billion investment portfolio, including a majority stake in a dozen Manhattan buildings with 6 million square feet of commercial space. “They were considered the real estate gurus,” explains Richardson. “It was logical to call them for advice.”

Richardson’s call ended up leading to much more than just advice on land management. Indeed, it soon became clear that the highly resourced parish and the seminary shared a common vision for developing neighborhoods and assets, and most importantly, a common vision for how to most effectively prepare leaders for the church. Trinity Church wants to create a globally focused Anglican/Episcopal leadership institute, says Richardson, and together, the two organizations hope to develop nonaccredited programs for Anglican leaders around the world.

In April 2019, the two institutions announced that Trinity Church had acquired CDSP, and that its governing board (called the parish vestry) will serve as the seminary’s governing board. However, Trinity’s vestry will not actively manage CDSP, according to William Lupfer, the rector of Trinity Church since 2015. “We will have staff members supporting the folks who are currently managing CDSP.”

The announcement, which came after more than a year of confidential negotiations, hinted at some of the reasons the parish decided to acquire the school. “CDSP’s curriculum, which focuses on mission, discipleship, and evangelism, along with community organizing and core leadership skills, shows a clear understanding that the church needs to prepare leaders in a substantially different manner than we have in the past,” wrote Lupfer in the official news release about the alliance. “Trinity is committed to a strategic focus on leadership development and to growing our global partnerships — commitments that align with CDSP’s mission.”

According to a CDSP press release, the church and the seminary “expect to maintain the current management, faculty, and staff at CDSP for the near future.”

In the meantime, the seminary will be able to renovate, upgrade, and build over the next 5–10 years. Basic deferred maintenance at CDSP is now being addressed, says Richardson. As a start, they installed a new elevator and a new boiler and fire safety system.

Vancouver School of Theology - Vancouver, British Columbia

Vancouver School of Theology (VST) has an affiliation agreement with a larger university — the massive University of British Columbia (UBC), with its nearly 65,000 students on two campuses. But affiliation doesn’t mean financial support, and 10 years ago, VST was facing the same challenges as dozens of other theological schools: old buildings in need of repair, a changing student body, and a shifting educational model that required more technology and less student housing.

At that time, VST occupied the historic Iona Building on the leafy UBC campus, a 100,000-square-foot structure on a parcel of land VST had been leasing from UBC since 1927. But, following a comprehensive review of its programs, the VST board concluded that the seminary required different facilities. For nearly one and a half years, the VST board, faculty, and senior staff reviewed how the institution could best fulfill its mandate. They decided to approach UBC with an offer to sell the Iona Building.

VST sold the building to UBC for 28 million Canadian dollars (about $21 million USD), the proceeds of which provided the school with the resources to do a gut renovation of another building it already owned — a 25,000-square-foot student residence called Somerville House which they would use as an administrative building repurposed for the delivery of theological education to both on-site and distance education learners. “Using an existing building helped speed up the permissions required and expedited the finished project,” says Richard Topping, VST principal. According to the VST website, the sale “also enabled the establishment of the VST Foundation, which now holds the bulk of the assets from the sale, guaranteeing a financially robust future for VST students for many years to come.”

Since reducing its footprint — moving to a smaller building and eliminating the library and student housing — programs have increased, enrollment is up, and distance learning now represents a greater percentage of its course registrations than before the move.

[EDITORIAL CLARIFICATION, January 28, 2020: After publication, In Trust received the following note from Richard Topping, principal of Vancouver School of Theology, regarding the last paragraph above: "There are two details about VST that are not quite correct. VST hasn’t eliminated either our library or student housing. We downsized the physical collection and have significantly increased our electronic resources – journals and ebooks in particular. This allows us to support the research and learning of our growing body of online and commuting students. While we no longer have a residence of our own, our partner, St. Andrew’s Hall, provides residential accommodation for our students.”]

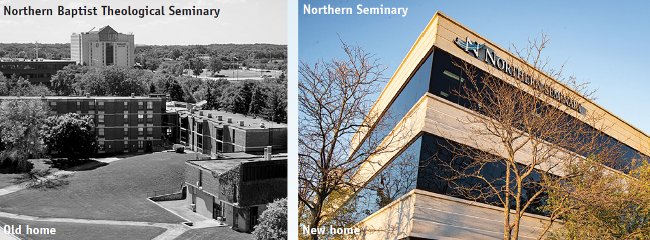

Northern Seminary - Lisle, Illinois

In 1963, when Billy Graham gave the keynote address at the dedication of the new suburban campus of Northern Baptist Theological Seminary in Lombard, Illinois, the school boasted a brand new administration building, a library, a building for classrooms, and another for student housing. The move from Chicago to Lombard was a unique opportunity for Northern to make room for growth.

But 50 years later, the Lombard campus had so much deferred maintenance that a financial analysis suggested the seminary could save $7 million by giving away its campus. That analysis went a long way in persuading the board that the seminary had to move, says Bill Shiell, president of Northern since 2016.

But there was also another reason to relocate: the seminary’s decision to offer new models of educational delivery. Increasingly, seminary students were living off campus, taking classes online, and working full- or part-time. This new delivery model allowed Northern to fulfill its goal of training pastors where they live – without leaving their homes and faith communities. The result was an underused campus with high overhead, especially the student housing building.

A refocused mission statement helped drive subsequent campus changes, Shiell says. “We didn’t need a big campus and student housing — we needed modern facilities and infrastructure tech to let us do the business of seminary.”

After looking at various options, the board decided to sell the campus and move to leased space 6 miles away that was located, conveniently, right on an interstate highway. Also, at about the same time, the seminary opened the Center for Urban Leadership on Chicago’s South Side to serve students ministering in an urban context.

Lexington Theological Seminary - Lexington, Kentucky

Not so many years ago, Lexington Seminary, affiliated with the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), had a traditional downtown campus with mature trees and wide walkways. Spread over more than 7 acres were 44 apartments, 22 townhouses, an administrative building, and a chapel with a large fellowship hall — all of which were underused. With shrinking enrollment and challenging deferred maintenance costs, the seminary was operating in the red. And then the 2008 recession hit. The board decided it had to act quickly.

“Those stark realities meant we didn’t have the luxury of going through a long decision-making process,” says Charisse Gillett, the seminary’s president since 2011. “Raising money wasn’t going to solve the problem because that wouldn’t resolve the low enrollment.”

To improve the preparation of students for parish ministry, Gillett and the faculty started restructuring the curriculum and educational delivery method. Gillett says that the data they had been looking at suggested a need for pastors who are well equipped to teach and preach, but who are also able to lead a board and take care of parish finances. Eventually, the seminary embraced a competency-based education model that required students to achieve multiple learning goals like “leading the church” through worship, care, formation, and more, “interpreting Scripture to the church,” and applying the Gospel message to varying sociocultural contexts.

In 2013, Lexington Seminary sold its campus and buildings to the nearby University of Kentucky for about $13.5 million. By the next year, the seminary completed a move to a more practical location — 16,000 square feet of leased space in a commercial office setting, with room for classrooms, a library, a chapel, and administrative offices, but no apartments or dorms.

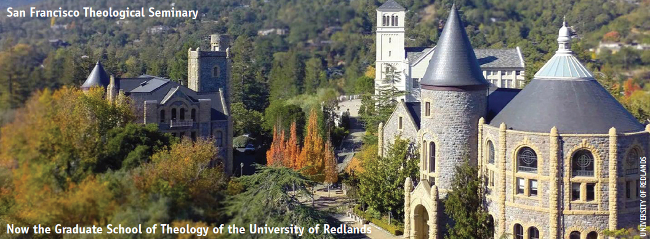

San Francisco Theological Seminary - San Anselmo, California

In 2015, James McDonald, president of San Francisco Theological Seminary (SFTS), was facing a host of problems. The seminary, which he had recently been appointed to lead, was challenged with low enrollment and high deferred maintenance costs. In other words, he was grappling with how to remain relevant in a rapidly changing world.

So, the school cut expenses — even though McDonald knew that would only take them so far — and began to offer more distance learning. Yet despite the challenges the seminary was undergoing, two years ago, when Jim McDonald introduced himself to Ralph Kuncl, president of the University of Redlands, he was not thinking about a merger. After all, the two schools are 450 miles apart — one in Northern California’s Bay Area, and the other in Southern California’s Inland Empire. Still, half an hour into their conversation, realizing how much they had in common, the two decided it seemed logical to start a conversation about possibly merging the two institutions. Talks advanced quickly and the merger between the two schools was completed in 2019, with the seminary becoming a graduate division within the larger university.

Today, post-merger SFTS looks the same as it did before, with the only apparent change being the sign on its San Anselmo campus that reads: University of Redlands, Home of San Francisco Theological Seminary. SFTS does not yet have a presence on the university’s campus in Redlands — that will happen later, when some of the faculty and certain programs and classes move there.

The board’s role

What did these schools do to focus on their missions while building economic vitality? They started by facing the facts and understanding their challenges.

First, develop a strategy based on reality

Once the board of Missio Seminary made the decision to move from the suburbs to the city in 2015, they developed a strategic five-year plan (covering 2015 through 2020). In 2018, the board appointed a relocation task committee from within the ranks of the board and hired a consultant with experience in real estate and law.

Location scouting was the first step. Even though Missio board member Rebecca Campbell has extensive real estate experience, she didn’t feel qualified to make final real estate decisions for the seminary. So the board hired a commercial real estate consultant who provided a framework to start with, using criteria such as proximity to public transit, highway access, local activity, general safety, and appearance of the neighborhood. The consultant “encouraged us to envision a location that embraces the message we want to convey in our brand presentation,” Campbell explains.

After scouring the city for the right spot, they found several promising locations. One, near the Philadelphia Museum of Art, was such a serious contender that the board asked for renderings from an architect and cost estimates from an engineering firm. But the prices “caught all parties off guard,” Campbell says. “Even with value engineering, the excessive construction cost completely stalled the process on that location.” Ultimately that site was dropped.

Once again, the relocation committee met and reviewed their needs, wants, and finances, ultimately deciding they could manage with less space than they originally anticipated. The next site they looked at was in the same Art Museum neighborhood and was within their price range. Furthermore, because it only needed minor renovations, turnaround time promised to be quick. Negotiations were well underway when the whole deal fell through. A tenant of the building they were interested in had a rental contract that allowed them to screen new tenants and reject them if they were an educational institution. That was the end of that.

Missio finally found its new location in January 2019: the top floor of an industrial loft building in the Callowhill neighborhood — adjacent to the previous home of the famed rock music venue, the Electric Factory. Campbell says the upside of their very long search was that “when we finally found our location, we had our game together.”

Even though the relocation project took years to complete, the Missio board decided to keep using the assistance of the real estate consultant. As Campbell reports, he helped the seminary navigate each surprise. She says that “a flexible mindset was vital in this relocation process.”

In advance of the move, the board also formed an advisory council of urban clergy to foster connections in Philadelphia. The council helped spread the word that the seminary would be moving to the city. News of the relocation of Missio may have prompted the mayor of Philadelphia to invite Missio’s president, Frank James, to join the Overdose Prevention and Harm Reduction subcommittee of the Mayor’s Task Force to Combat the Opioid Epidemic in Philadelphia. James thinks that his participation on the task force was a signal that the seminary is concerned with social justice and urban challenges, not just with its own students, James says.

Get to know the players and partners

The prospect of incorporating Church Divinity School of the Pacific into Trinity Church Wall Street — a California school into a New York City congregation — required time to discern whether the “two institutions had sufficient complementarity to work together,” says CDSP’s dean, Mark Richardson.

Countless videoconferences, phone calls, face-to-face meetings, and sharing of publications and papers helped each side learn about the culture of the other. Trinity Wall Street, as its name suggests, lies in the heart of New York’s high-flying financial world. Its governing board includes financiers and business executives, and its culture is professional and even corporate. CDSP, on the other hand, is at home in Berkeley, where community organizing, pluralism, and social justice have been longstanding key values.

The integration process, initially led by a consultant, included a steering committee with working groups in finance, academics, and others. Eventually, the two organizations drew up letters of intent and then a final contract of acquisition, which were signed by both boards in March 2019. The CDSP board voted to dissolve itself effective on the date of the formal agreement.

The consequences of being acquired by a multi-interest institution like Trinity Church — with its formidable real estate portfolio, multiple outreach programs, Connecticut conference center, historic cemeteries, and its three landmark church buildings — is a bit of an unknown for CDSP. “We are now under the governance of a body that has multiple interests, whereas before our former board had as its sole interest the school,” says Richardson. They have yet to see what this will mean for the seminary down the road.

Retain one’s identity

Even when a sale or merger will give a school a much better chance of thriving, to part ways with a much-loved campus, or to drop programs or lay people off, is painful. The seminaries we spoke to made it clear that, when in such a position, retaining a school’s unique identity was important. When San Francisco Theological Seminary and the University of Redlands merged, the SFTS board was dissolved, but three of its board members were incorporated into the 39-member Redlands board. University president Ralph Kuncl says that this was a way of “integrating two cultures.” He adds: “If you don’t incorporate the two boards in some way, you risk losing all the best aspects of [SFTS] history, and also not being good stewards of what’s there.”

Engage people with the right skills

Having a board that is composed of people with different kinds of expertise is important at all times, but it can be especially valuable in times of change. For example, the Vancouver board was able to use the expertise of the architect and accountant on its board when they were selling a building and renovating another.

But as important as internal expertise is, so too is recognizing when you need outside expertise. The board of Missio Seminary hired a branding expert to help with the name change. Even though board member Rebecca Campbell has plenty of commercial building expertise through the company she and her husband run, the board also hired a real estate consultant to help find a new location. Campbell says they would have been lost without him. “He gave hundreds of hours. I learned more from him sitting there in our meetings in the last four years than I would have learned in an MBA program.”

When the board of Northern Seminary decided to move, internal debate over the new location led the board to seek outside assistance. They talked to leaders at other seminaries who had been through the same thing. Those discussions “demonstrated the need to decide where you’re going first, before selling the campus,” says President Shiell. “That took away the mystery in the timeline and lowered the anxiety of our community. The board also decided to hire temporary relocation staff which helped with the stress levels.”

When San Francisco and Redlands considered merging, they hired Wells Fargo to conduct an independent financial analysis, an audit firm to look at past financial data, and a law firm to draw up the merger agreement, says Kuncl, the university president. To oversee the process, the board appointed a four-person committee, including two past chairs and two people with special expertise in real estate and finance.

Much depends on character

While having the right expertise at the table is important — on the school’s staff, on the board, or in the Rolodex — so too is the character and personality of these key players. “You need to be flexible to navigate such times of change,” says James Stellwagen, a member of Northern Seminary’s board. “Human nature is resistant to change, and that’s even harder when you’re a group. So it takes a lot of faith and confidence with each other and staff.”

Missio’s Rebecca Campbell agrees. “When you’re hit with obstacles, you need people who are able to pivot. Hitting an obstacle doesn’t mean you’ve gone in a wrong direction,” she adds. “The things that stopped us were unforeseen — like a location that appeared perfect at first but wasn’t.” But she points out that board members need to keep the bigger goal in sight. “The Lord doesn’t ever take us in a straight line,” she says. “Our faith is built and becomes more robust with obstacles.”

She also thinks board members have to be “graciously assertive.” “If you want me on the bus, you have to be willing to hear what I have to say, or I’m not getting on your bus.”

When Lexington’s board was reconfiguring itself, board members spent considerable time looking for specific qualities in additional members. “They had to be stakeholders — serving congregations that contribute to the school,” says Gary Kidwell, a member of the board since 2000 and board chair for six years. Just as important, though is “good chemistry” and “good negotiating skills.” Grace plays a part too. Kidwell recalls that some board members felt called to serve when the seminary was at its most unstable. Some of these volunteers then stepped down once the school was on more solid footing.

Handling dissent within the board

When faced with the need to make major changes at a school, it is not uncommon for there to be some disagreement among board members about what direction to take. It’s a situation that requires careful navigation, especially for Christian institutions, where people tend to avoid conflict and place a premium on fairness and equality.

Most schools report very little disagreement within the board about how to face big changes, although Kuncl, the president of Redlands, admits that there was sometimes “a little strategic maneuvering in the background, [when you’re] trying to inform and educate resistant trustees.” To address the concerns of some of the University of Redlands trustees that the school might be acquiring a “money pit,” the board met and “those who went had their hearts changed within 15 minutes,” he says.

When Missio embarked on both a name change and a move, “some questioned the wisdom of it being simultaneous,” says President James. “But we had to move forward with our strategic plan.” That included doing many things at once.

Board member Rebecca Campbell confesses that she was sometimes the dissenter on the board. “We looked at one place, and when I walked in I said, ‘Absolutely not,’” she recalls. “I see a roof unrepaired, unprofessional management, and other things that made me question whether we would be represented well by these landlords.” The board passed on that particular space.

According to Dean Mark Richardson, when CDSP was considering its partnership with Trinity Wall Street, the board discussed whether a merger would move CDSP in the right direction and help them achieve their mission. “The major concerns were how to hold on to the legacy of the school and to secure CDSP’s future integrity,” he says.

Richardson says the hard work was “getting the board to understand our school would be better than before, and to understand that the current financial pressures wouldn’t allow us to be as creative alone as we could be in partnership.”

If it hadn’t been couched in terms of “a mutual larger mission,” he adds, “it would have been just a transaction, which wouldn’t have been acceptable to our board of trustees, alumni, or students.”

What helped at CDSP was a history of “candid board conversations about the seminary’s future long before Trinity was involved,” Richardson says. “We had already honed our skills in discussing difficult things. Not surprisingly, there were sometimes disagreements, but it was a step everyone agreed had to be taken to ensure CDSP would have a strong future.”