It's not an easy time to be the CFO of a theological school—or a seminary board member, for that matter. Those entrusted with the financial care and well-being of theological schools seem to get only two kinds of news these days: bad and worse. Seminaries are feeling the effects of the global recession, and those that rely on income from endowments and other long-term investments are taking a serious look at their financial future.

How bad is it? "Probably the worst since the Great Depression," says Anthony Ruger, senior research fellow for institutional resources at Auburn Theological Seminary's Center for the Study of Theological Education.

The fourth quarter of 2008 ended dismally, and most prognosticators are not predicting a bounceback anytime soon. Higher education endowments fell 23 percent in the first five months of fiscal year 2009, according to a survey by the National Association of College and University Business Officers. This follows a 3 percent decline in FY08, according to the 796 colleges and universities in the United States and Canada who responded to the survey.

It may be little comfort to know that many seminaries, educational institutions, and nonprofit organizations are in the same leaky boat. Virtually all investments—whether donor-restricted endowments, board-restricted investments (sometimes called "quasi-endowments"), or other long-term investments—have been hit by the market's decline.

Even responsible investors with diversified portfolios have not escaped the deep losses in both the stock and bond markets in the past year. "There was no place to hide," says Ruger, a respected financial adviser to theological schools. "Even those boards that did a very careful and thoughtful job of investing got hit. People did not see this coming in its severity."

Schools that don't rely heavily on their investments may sit sympathetically on the sidelines (although the economic downturn has likely affected their sources of funding too), but a third or more of the schools accredited by the Association of Theological Schools in the United States and Canada have significant endowments and thus need to get a handle on how the market is affecting one of their major income sources. Ruger suggests schools do the math to find out how bad their losses will be—and when to expect them.

The writing on the wall

Many seminaries follow the common wisdom in higher education to spend no more than 5 percent of their long-term investments, based on a three-year rolling average of their accumulated market value. But using this average can hide the seriousness of the losses. "With a three-year average, next year doesn't look so bad," Ruger says. Of course, the deep declines in the value of most portfolios over the past four quarters will mean 5 percent of a much smaller number in future years.

Cautious schools that have been spending less than 5 percent may have provided themselves with some protection. For example, imagine a school that spent 4 percent of a $10 million endowment in FY08—that means the endowment contributed $400,000 to the school's budget during FY08. If that endowment dropped by 20 percent between July and December 2008, it's now worth only $8 million. If the school raises its endowment draw from a prudent 4 percent to a still-healthy 5 percent, then the $8 million endowment can still contribute $400,000 to the annual budget.

Of course, those schools that have been spending more than 5 percent of their three-year average will be hit even harder, Ruger points out.

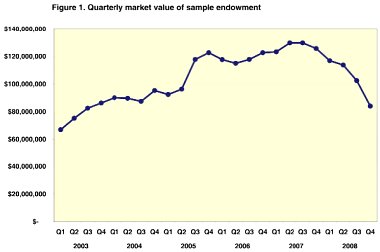

To determine the scope of those losses, Ruger starts by simply plotting a sample endowment's market value over the past five years to show the ups and downs graphically (Figure 1). It is not unusual to see losses of 25 percent or more in the past year, although the amount varies from school to school, depending how their assets have been invested.

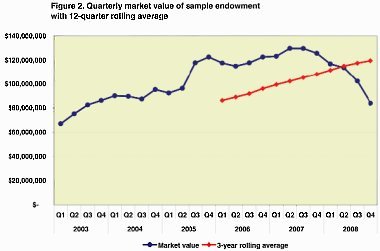

Next, Ruger calculates the spending rate, using an average market value based on the past 12 quarters. When the market fluctuates normally, that average value still slopes smoothly upward (Figure 2), as does the spending rate. "It responds to the market but it still increases, because even if you have two bad quarters, they're only two of the 12," says Ruger.

But today's economic crisis means steeper losses from a longer period of time, forcing schools to increase their spending to 7 or 8 percent of their investment portfolios—or even more—to make the same income. Overspending from investments can have serious consequences, especially if the market does not bounce back quickly.

But will it bounce back quickly or not? Ruger has no crystal ball. "Some say it's going to get worse, and others say it's going to get better."

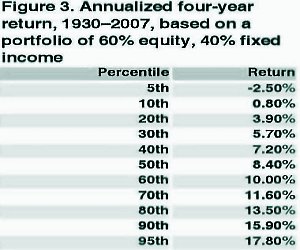

For the sake of planning, he recommends using data from annualized four-year returns from the past 70-plus years, based on portfolios invested 60 percent in stocks and 40 percent in fixed-income investments, like bonds (Figure 3). From this he calculates two projected market values and spending rates—one using an average return of 10 percent (which nearly any CFO would love to have right now!) and the other a more conservative rate of 3.9 percent.

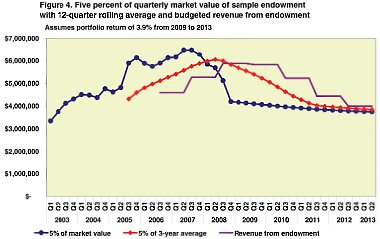

For this sample school, Ruger finds that the more conservative rate means that while 2009 will not be critical, the institution faces major losses in the following three years. A 5 percent spending rate combined with a mere 3.9 percent return means that the portfolio's value will continue to shrink (Figure 4). Revenues from the portfolio would decline by 32 percent over three years, if the school were to maintain its 5 percent draw. "That's a big cut," Ruger says. "It's why people are losing sleep."

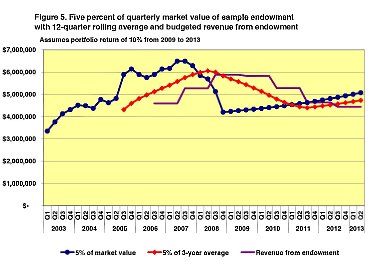

But what if stock market values improve? Looking at a more optimistic rate of 10 percent growth over the next three years, the portfolio's three-year rolling average will continue to decline through 2011 (Figure 5). A budget allocation based on spending 5 percent of the portfolio's three-year average will decline about 25 percent over the next three years. "So even if things go pretty well, people will still face a serious loss of endowment revenue," Ruger says.

Good news for the prudent: Schools that have been using formulas that restrain spending and help smooth out volatility in the market, such as the "snake in the tunnel" rule or the "Yale formula," may rebound more quickly. "Obviously, if you were underspending, you do better in the lean years," he says.

But while these strategies offer some protection, during the current recession, "no matter what formula you've been using, you're going to lose revenue," Ruger says.

Where to go from here?

Armed with realistic estimates of how the economic downturn will affect their schools' long-term investments, boards can turn to the sobering task of bridging the funding gaps, whether with other sources of revenue or by cutting expenses.

"Here's where schools vary greatly," says Ruger. "Some schools are very dependent on their endowments and may be looking at a 12 to 16 percent gap in overall revenue. That's a hard challenge when a school has a lot of fixed costs."

The scale of the problem may dictate the speed with which it is dealt. A relatively modest deficit may be dealt with quickly, though not painlessly, Ruger says. More significant losses may take longer to rectify, especially if the cuts drastically compromise the school's programs. Many institutions are already living leaner, putting faculty searches on hold or curtailing unnecessary travel.

Strategies for cutting expenses or raising revenue usually fall into five categories:

-

Shrink. Resizing or downsizing can mean reducing programs or even, as a last resort, reducing faculty.

-

Sell. Real assets can be a source of revenue. Some schools have sold the president's house. Others have taken the drastic step of putting the entire campus on the market.

-

Review. A careful review of programs may mean dropping or scaling down some programs but adding or expanding others.

-

Share. Partnering - even formal mergers - can save money by sharing costs, especially on facilities.

-

Borrow. But borrowing money sometimes merely postpones the inevitable, Ruger says.

Fundraising can help relieve financial stress, especially if the school already has a donor base. "If schools are doing a good job of telling their story, helping people understand the good that they are doing, then there are people who still have money to give," says Rebekah Basinger, one of In Trust's Governance Mentors.

In the end, after doing this financial analysis, boards must ask the hard questions facing their institutions. Given the pessimistic predictions about the market, when can an institution expect to be back on track with previous rates of income? How much cutting can a school do without sacrificing its mission? If a seminary overspends its endowment, what will that do to its financial stability in the future?

"This is where board members are crucial," Ruger says. "They have the vision, but they are also dispassionate and clear-eyed enough to make the hard choices. With their steady hands, they can help steer schools into the future."

"The rainy day for which we prepared"

"This is the rainy day for which we prepared," says David McAllister-Wilson, president of Wesley Theological Seminary in Washington, D.C. "This is the rainy day for which we prepared," says David McAllister-Wilson, president of Wesley Theological Seminary in Washington, D.C.

For years, the administration and board of the 500-student United Methodist school had operated with balanced or even surplus budgets. They had spent their endowment conservatively according to the "snake in the tunnel" strategy and had increased their planned giving donations.

"We were on the right track, doing everything we were supposed to do," McAllister-Wilson says of the school's strategic plan to decrease dependence on tuition by increasing their long-term investments.

Now those investments have shrunk from $36 million to $24 million, and McAllister-Wilson doesn't expect them to return to their earlier values for years.

"It's certainly going to affect us," the president says. "There's no way to avoid the pain, and we've already taken a lot of the pain this year."

But Wesley is ready to ride out the financial storm. McAllister- Wilson and his board decided to cut program funds and didn't fill some positions, yet they have continued their faculty searches and funding financial aid. And, thanks to years of good endowment management, a strong surplus, and good gifts, they have decided to take the risk of having an operating budget deficit for a few years.

McAllister-Wilson draws on another water analogy: "When a ship is in rough seas, you do three things: bail, keep moving, and keep the bow up," he says. "We're bailing as much as possible, but we're keeping moving and keeping the bow up."

He doesn't want to rely exclusively on bailing or cutting, lest those cuts damage the school's competitiveness for student recruitment. "We're willing to live with several years of operating budget deficits, if by doing so we're able to keep moving forward as an institution with our strategic mission."

At Providence College and Theological Seminary in Otterburne, Manitoba, belt-tightening is nothing new. At Providence College and Theological Seminary in Otterburne, Manitoba, belt-tightening is nothing new.

With 150 seminarians and 350 undergraduates, the evangelical institution has an operating budget of only $7.5 million and annual revenues of $35,000 from a small endowment. Still, with losses of 5 to 10 percent in their portfolio and declining overall institutional enrollment, the school has not escaped the effects of the economic crisis.

"A lot of Christian schools in Canada have been affected by enrollment downturns in the last two to three years," says August Konkel, the school's president. "The economy definitely has something to do with it."

Providence had to make $1 million in cuts over the past two years, including reducing staff and faculty and cutting professional benefits. Increased seminary enrollment actually helped the bottom line.

After operating with a $250,000 deficit this year, the school has balanced its 2009-10 budget, as advised by its board. Getting a handle on their financial picture has helped Konkel make some tough decisions. "We feel we've been able to get into a position of relative stability," he says.

|