|

|

Gone are the days when a trustee served a theological school because of the prestige attached to the affiliation. Gone too are the days when board membership was an “activity” for someone hoping to pad a resume. Given the legal and fiduciary responsibilities facing boards today, board service is both a type of stewardship and a serious commitment. And the best time to identify new board members is long before a term ends or an unexpected vacancy occurs. Gone are the days when a trustee served a theological school because of the prestige attached to the affiliation. Gone too are the days when board membership was an “activity” for someone hoping to pad a resume. Given the legal and fiduciary responsibilities facing boards today, board service is both a type of stewardship and a serious commitment. And the best time to identify new board members is long before a term ends or an unexpected vacancy occurs.

In my years as a consultant specializing in board development and evaluation, I have worked with dozens of governance groups that have learned the steps of what I call the delicate dance of recruitment. Just as in learning to waltz or wooing a spouse, there are sometimes a few stumbles along the way. But even when it goes smoothly, the process of recruiting new members requires surveying the field, engaging in meaningful getting-to-know-you discussions, finding common ground, and, yes, even having the right chemistry. Based on my experience, I recommend six steps for launching into a beneficial and long-term relationship.

-

Refresh the pool

Assessing prospective board members should begin months or even years before a new member’s election and first meeting. This means that the committee charged with recruiting — which may be called the “trustee committee,” the “governance committee,” or the “membership committee,” among other names — needs to be active throughout the year and not just when board vacancies occur. They should constantly cultivate potential new members, keeping a pool of names, to ensure that the required expertise is represented on the board.

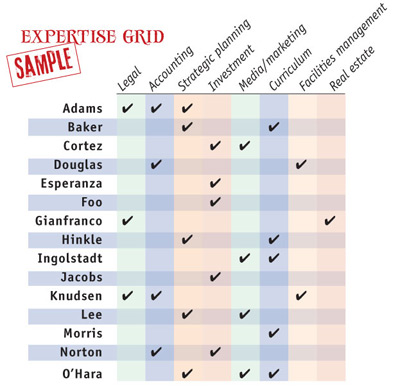

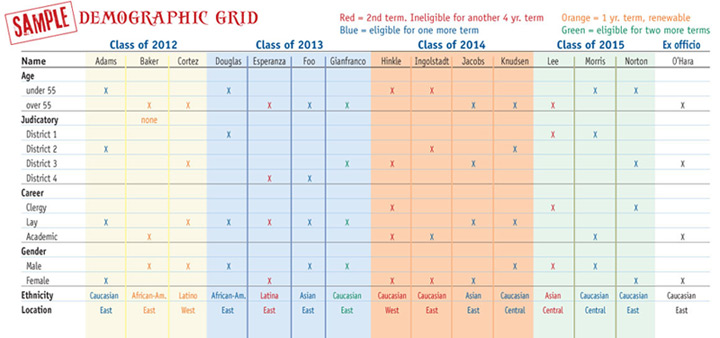

Every year or two, this membership committee should construct a board grid or two that include current board members, their demographic information, and their current areas of expertise — legal knowledge, strategic planning, human resources expertise, communications, budget acumen, and more. This grid exercise can provide an up-to-date profile of the board, illustrating members’ strengths and interests along with demographic information. Just as important, it immediately indicates what talents (and what diversity) the board may be lacking. Two sample grids are included here.

-

Look beyond professional skills

Once the grid reveals the areas of professional expertise that are needed, it is important to consider more personal characteristics that a well-functioning board needs — like the ability to collaborate with colleagues, keep information confidential, and discard personal agendas. For example, board members who represent a particular constituency do bring special knowledge about that sector to the board, but they cannot compromise their responsibility for the whole institution in favor of the particular interests of that one constituency. And every board member needs to practice discretion — prospective board members may need to be reminded from the start that they should not speak on behalf of the board outside of meetings (for example, by talking to reporters or addressing church groups).

- The importance of fit

After the president, the board chair, and the appropriate committee assess the kinds of people needed on the board, they need to strategize how to find, cultivate, and recruit those people. All board members can be invited to share the responsibility of suggesting the names of potential members, always remembering that friendship is not a primary qualification. Indeed, board members operate in many professional and personal circles, and ideally they know the school’s mission so well that the “fit” of potential members is evident.

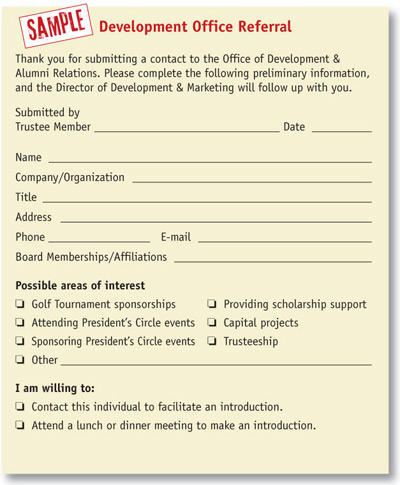

Some boards distribute a contact sheet from time to time, like the sample one shown here, asking current board members to suggest names, qualifications, and other relevant information about possible recruits. But not all smart people embrace the mission and culture of a theological school, and not all “good church people” have the expertise to understand the legal, educational, and fiduciary issues and policies that routinely come before a board. It’s critical that the president, chair, and committee think strategically and critically about candidates before they start issuing invitations.

- Conduct onsite interviews

Most boards expect the school president and the board chair to meet with potential members — sometimes including in the discussion the member who offered the recommended in the first place. Face-to-face meetings are critical: Potential members need the opportunity to articulate their qualifications and motivations for service, and the president and board chair need to discuss the school’s needs and outline their expectations for good board membership. This is also the time for the president and chair to disabuse potential board members of misperceptions about the school.

All schools have institutional cultures that set them apart, but the culture of a theological school can be especially hard to communicate to someone unfamiliar with theological education. The mission statement is a helpful first step, and the bylaws will fill in some of the blank spots on the map, but in a face-to-face meeting, the president and chair can continue to color in the gaps, answering questions that a potential board member may not even know to ask. For example, are meetings more formal or more informal? Is the school “conservative” or “liberal” within its denomination or religious tradition — and how are these designations defined? Does the school look to history and heritage for patterns of institutional behavior and policy, or is it more cutting edge? How does the school relate to the wider culture — neighborhood, town, and country? Is it known for being friendly or aloof, political or spiritual (or both), more practical or strongly academic? Is the campus a community gathering place or a quiet haven? Are events open to the public? It is incumbent upon those who are recruiting new members to make these aspects of the school known.

- Great expectations

Some theological school boards have statements of expectations for board members, and some do not. In general, however, every board should expect that its members are fully committed to the school’s mission and are willing and able to attend full-board meetings and serve on one or more committees. While the giving of time, talent, and treasure may strike some as clichéd, these three attributes remain critical. Time means the willingness and ability to attend general and committee meetings as well as a desire to take active part in varied seminary events. Talent means that a member shares expertise and abilities generously. Is this potential board member willing to work hard?

Generosity also encompasses that third T — treasure. Every board member must contribute to the annual fund and other development efforts generously, according to his or her own means. Whether expectations for personal giving are explicit or implied, the president or chair should make those expectations absolutely clear before the newcomer joins the board. At the same time, board members should recognize the importance of making introductions and accompanying the president or board chair on solicitation visits when appropriate.

Potential board members also need to know that they will occasionally engage in strategic planning, evaluate the school’s governance structures and its president, and participate in board self-evaluation. Schools embedded in a university structure, and those answerable to a denomination, diocese, or religious corporation, present a special complexity that must be explained carefully to future board members.

It is important, too, that potential members educate themselves about the needs of the church, the needs of the theological school, and the relationships — internal and external to the school — that are crucial for the institution’s ongoing health. A serious interest in, and understanding of, the broader religious landscape should be a long-running quest for board members. And it goes without saying that all members should learn basic knowledge of all functional areas of the seminary.

- Pursue diversity, avoid tokenism

Most board members will nod in agreement that diversity is a good thing, but it’s not always clear what diversity even means. The old ways of building a board included slots such as “two women, one Hispanic, two African Americans, one recent graduate.” Such efforts may smack of tokenism and may not be helpful. While racial, ethnic, and gender diversity are important, it is incumbent upon a school to consider more—age, geography, and, in some cases, perhaps even religious affiliation. Taking care to improve a board’s diversity enhances the benefits that accrue to the board from serious consideration of the skills, talents, and experiences revealed in the grid.

My experience with boards over the years has shown me that the above considerations contribute to ensuring healthy board functioning and fine relationships. Finding and welcoming new members is an exciting and important process — indeed, it is a courtship that can and should lead to meaningful long-term relationships. Like courtship, it is not something to take lightly or do sporadically. The health of the school, and its happiness, depends on this.

|

|