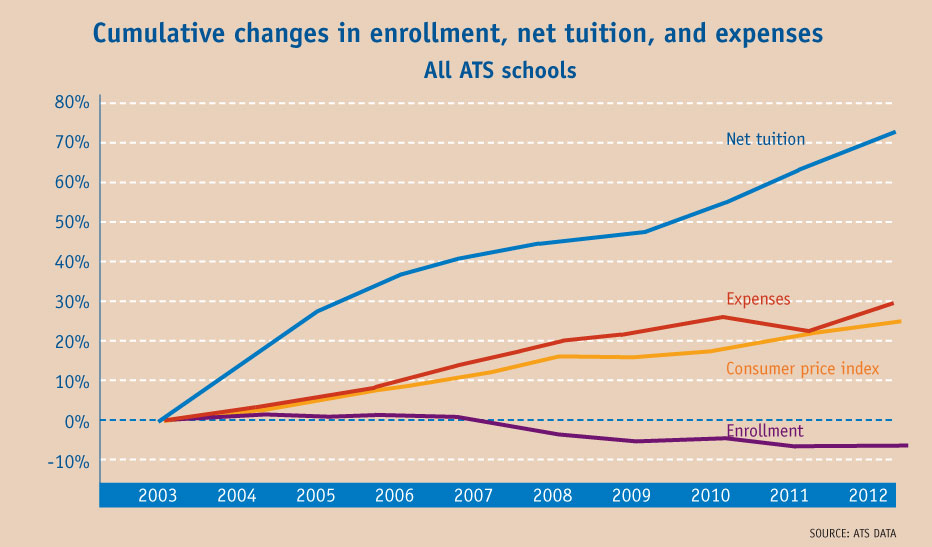

Let me describe theological education as an “industry.” We are part of an industry that has a vital mission that serves the church. But, over the last decade, our student market has been in decline. During this decade we haven’t adjusted our expenses in response to a shrinking market. Rather, expenses have risen even faster than the consumer price index.

How has this deficit been filled — the gap between bodies-in-seats and ever-growing costs? More gifts and grants, to be sure, but also dramatically higher net tuition revenue (that is, total tuition dollars minus the provision of financial aid). As an industry, we have balanced our budgets by charging fewer students ever-increasing tuition after scholarships. To finance their more costly degrees, students are borrowing more and more.

This is the storyline at my institution, Asbury Theological Seminary. And this story has been sparking important conversations about our future. We seek missional vibrancy with economic vitality. Since we’re typical of theological schools as a whole, I’m guessing that those stimulating discussions are happening from coast to coast.

If the conversations haven’t yet started at your own institution, it may be time to gather the data and share it among key stakeholders. You will be surprised at how quickly people get engaged in important discussions about your future.

The status quo is not sustainable

With data this startling, it’s easy to see why some theological school leaders are taking the initiative to create a new future for their institutions. But others are not. After all, many leaders are so focused on just getting through this year that they hardly have time to envision a future that may (or may not) come to pass. Businesses often have a difficult time realizing when their economic models are unsustainable. How much more difficult is it for leaders of theological schools!

Vijay Govindarajan, a professor at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth, offers an exercise that I’ve found helpful in visualizing my school’s plans for the future:

Pull out a stack of index cards, he says. Then write down every important initiative taking place at your school, one initiative per card. (For example, on one card you might write “Online degree programs”; on another, "on-campus bookstore.”) Next, find three boxes and label them. Box 1 is called “Manage the Present.” Box 2 is “Selectively Abandon the Past.” Box 3 is “Create the Future.” Or think of Box 1 as Luke 10:2 — harvesting the present crop of students. Box 2 is John 15:2 — pruning to allow new growth. And Box 3 is Matthew 13:3 — sowing seeds for an anticipated future harvest.

Now sit back and reflect a little bit about theological education ten years from today. Think about what kind of theological education will be needed then for church leaders, both lay and ordained. Consider all of the opportunities and threats surrounding changing student demographics, globalization, technology, delivery systems, student indebtedness, and government regulations.

With all this in mind, look back at the cards on which you've written your initiatives, and then toss each one into the appropriate box. If the initiative benefits current students or those you anticipate enrolling within the next three to five years, drop the index card in Box 1, “Manage the Present.” Take all of the index cards that deal with stopping something, or changing structures or policies that can free up resources, and put those cards in Box 2, “Selectively Abandon the Past.”

Finally, take those initiatives that prepare your school for the long term (i.e., five to ten years in the future), and place those cards in Box 3, “Create the Future.”

This simple assessment exercise gives you some clues as to whether your school might have the right balance in managing the present, selectively abandoning the past, and creating the future.

Why do institutions spend too much time managing the present?

Most organizations — whether businesses, government agencies, nonprofit organizations, or schools — spend a lot of energy managing the present. Of course it’s essential to do that — a school must manage the present with excellence so that resources are focused with laser-like intensity on all the school’s goals — all with an eye to preparing current students for a lifetime of quality ministry or scholarship. It is within Box 1 that schools optimize their core competencies, seek quality improvement efforts, benchmark their performance with peer schools, assess student learning outcomes, and allocate resources.

There are other reasons, though, why schools may find it easier to live primarily within Box 1, managing the present. Some educational leaders may determine that their schools cannot effectively manage or cope with the conflict caused by adapting to changing market demands. Let’s face it — stories abound of presidents who have lost the confidence of their faculty and other key constituents when instituting big changes. Furthermore, some leaders are risk averse by nature or simply unwilling to consider any departures from historic educational models. As a result, presidents can retreat toward the relative comfort of Box 1 initiatives.

Abandon the past? Are you crazy?

If you’re serious about visionary innovation that will keep your school’s mission vital, remember this axiom: “A school cannot create the future if it won’t selectively abandon the past.”

You can’t if you won’t. So leaders have an important choice to make. No business or organization can afford the lack of organizational focus that comes with adding more and more programs onto existing ones. You cannot put the “new wine” of innovation for a new vision into the “old wineskins” of outdated policies and programs that were created for a former vision.

Of course, there are ethical issues to consider. In theological education, students are bearing an ever greater responsibility for helping their schools to balance their budgets, and so leaders need to be careful about raising tuition prices as they begin to prioritize the future. But if a school stays in Box 1, refusing to abandon the past or look to the future, then perhaps not only future students, but also past and present donors are being shortchanged. For example, are gifts coming in the door today being used to subsidize the status quo? How much more faithful would it be to use these gifts to adapt to the future!

This is even more likely to be the case with the gifts of faithful friends of the past, which are now invested in the school’s endowment. Donors to the endowment who passed away long ago, don’t need to be kept informed about what their gifts are accomplishing! In many cases, these endowed gifts are supporting programs that are no longer “mission-centric” and could never support themselves. But, the money is available, thus deferring tough choices about refocusing the use of those endowed funds to serve the changing needs of the church.

If your school is ready to get serious about selectively abandoning the past, then it’s time for its leaders — board, president, and faculty — to work through some questions. With the mission of your school clearly in mind, ask:

• Which programs are underperforming and need to be phased out?

• Which programs are underperforming and need to be redesigned?

• Which structures are outdated and need to be replaced?

• Which policies and practices are obsolete?

• Which strategies are ineffective?

• In what ways are established mindsets and biases preventing creative thinking?

This last question is perhaps the most challenging. In the Vijay Govindarajan and Chris Trimble article on this topic, “The CEO’s Role in Business Model Innovation” (Harvard Business Review, January-February 2011), the authors say that organizational memory can be one of the highest hurdles to overcome. They write: “As managers run the core business, they develop biases, assumptions, and entrenched mindsets. These become further embedded in planning processes, performance evaluation systems, organizational structures, and human resource policies” — and, I would add, in course catalogues and faculty handbooks. Govindarajan and Trimble warn that this kind of organizational memory is great for maintaining the present (Box 1), but if it isn’t held in check by some selective pruning (Box 2), then it hampers innovation (Box 3). “That’s why all Box 3 initiatives must start in Box 2,” they say. “Before you can create, you must forget.”

Pruning demands energy, analysis, sensitivity, and resolve. To cut programs wisely, you must first develop clear goals and objectives while prioritizing collaboration and transparency. And afterwards, you have to employ clear processes for evaluation and decision making.

What ought to be abandoned?

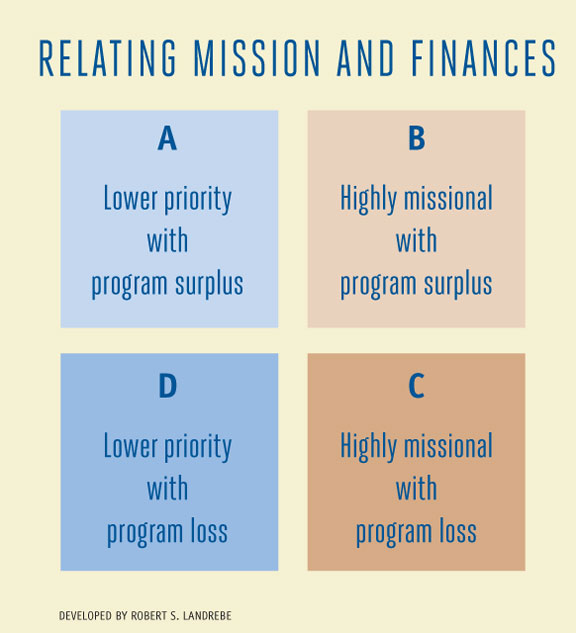

Let’s take a deeper look at one of the six questions listed above: “Which programs are underperforming and need to be phased out?” One way to approach this is to use the “Relating Mission and Finances” framework that I've adapted from business leaders (facing page).

To do this analysis, your school must be able to determine how much each of your programs costs, and whether each program is generating a surplus or requiring a subsidy from general operating expenses. Your chief financial officer should be able to do this, using an appropriate “cost accounting” basis to credit revenues to a program and attribute related costs to it. At a minimum, credit all revenues directly related to a program and subtract from those revenues the direct costs of operating the program. If your accounting systems allow for it, you’ll also take into account indirect costs, charging them to all programs on a consistent and fair basis.

Now, to use the framework on “Relating Mission and Finances”:

1. First, list all your school’s major programs.

These programs might include each of your master’s degree programs, doctor of ministry programs, Ph.D. programs, and lifelong learning programs, as well as student housing, food services, and bookstore operations. If you are a larger school, you can approach this exercise by evaluating campuses, extension sites, and distance learning programs and then drilling down to specific degree programs within each location.

2. Next, using an established, objective basis to evaluate how important the programs are to your school’s mission statement and vision, rank the programs from “highly missional” to “low priority” with regards to your school’s critical mission.

3. Then, using that same group of programs, determine which ones generate a surplus to support general operations. Then calculate which ones operate at a loss, requiring institutional subsidies.

4. Finally, based on this assessment, place each program in one of the four boxes in the framework. Programs on the upper right — those in Box B — are necessary if you’re going to subsidize any programs at all. Box D programs are prime targets for abandonment.

But, the analysis is the easy part. Next, leaders must give attention to a thoughtful plan of action. In many instances, leaders know that discontinuing a long-standing program has human costs. Faculty members may be invested in a program that needs to be phased out. Support staff may feel the threat of losing their jobs. Other constituencies may cry out that leadership is not giving proper respect to legacy programs loved by hundreds of alumni. Experienced leaders know the importance of gaining institution-wide understanding and acceptance of the need for pruning. They celebrate the past when programs are phased-out, honoring those who were part of it. When necessary, they also provide for those who will no longer play a part in the school’s future.

How do strategic thinkers instruct us to create the future?

There are many exceptional strategic thinkers who provide some useful tools and processes for seminary leaders to consider as they create the future in Box 3. Here are a couple:

There are many exceptional strategic thinkers who provide some useful tools and processes for seminary leaders to consider as they create the future in Box 3. Here are a couple:

» Clayton Christensen’s groundbreaking book The Innovator’s Dilemma includes business theories on “sustaining innovations” and “disruptive innovations” that can serve seminary leaders well. Christensen himself has applied his business theories to higher education. He writes:

The way we learn doesn't always match up with the way we are taught. If we hope to stay competitive — academically, economically, and technologically — we need to reevaluate our educational system, rethink our approach to learning, and reinvigorate our commitment to learning. In other words, we need disruptive innovation.

» Business Model Generation, by Alexander Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur, describes a “business model canvas” that is very compelling. The book’s final chapter, “Outlook,” describes how their principles can be applied to nonprofits, including schools. The authors also outline describe nine “building blocks,” with which schools can evaluate various scenarios incorporating new economic models.

Five of Osterwalder and Pigneur’s building blocks focus on the value they offer students through an analysis of (1) student segments (e.g., residential and non-residential students), (2) student value propositions (e.g., designing with the student in mind), (3) student relationships (e.g., self-service, “high touch”), (4) channels (e.g., residential campuses, extension sites, hybrid learning, online learning) and (5) resultant revenue streams.

The four remaining building blocks focus on cost efficiencies and effectiveness including (1) key resources (e.g., faculty and staff, buildings, technology, endowment funds), (2) key activities (e.g., academic programs, co-curricular programs, instructional design, admissions, student services, etc.), (3) key partners (e.g. denominations, outsourcing of food services, adjunct faculty) and (4) resultant cost structures.

Osterwalder and Pigneur set the table for a creative, Box 3 mode, in which seminary leaders can follow the entire “enterprise model canvas” to discern how to create the optimal future with collaborative efforts, while relying on God’s help.

Are you tinkering or setting sail?

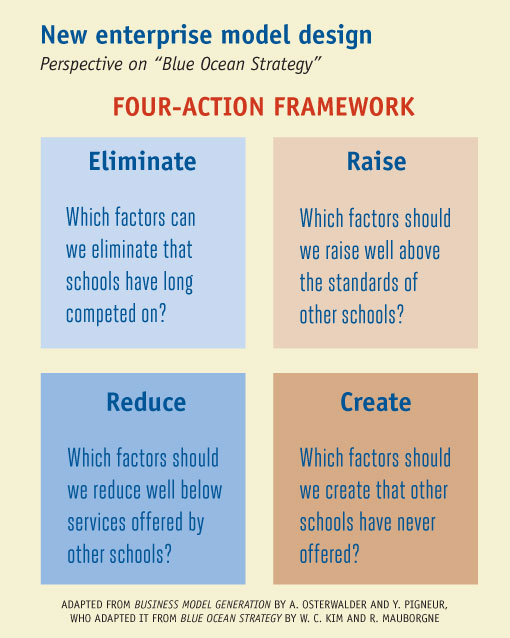

The nine building blocks described by Osterwalder and Pigneur come into play if a theological school chooses a conservative strategy of tweaking incumbent models, which is a valid strategy so long as it achieves the school’s long-term mission with long-term economic viability. But it’s even more useful if the school is pursuing a more risk-taking, “Blue Ocean Strategy,” seeking a new approach to meeting students’ needs through fundamental differentiation from what is currently offered.

How to do this? The four-action framework on the facing page asks strategic questions that address both abandoning the past (left hand side in blue shades) and creating the future (right-hand side in brown shades). On the left side of the diagram are questions about what to eliminate or reduce, targeting Osterwalder and Pigneur’s “cost efficiencies and effectiveness” building blocks. The right side asks questions about what to raise or create, which are associated with Osterwalder and Pigneur’s “value” building blocks.

It’s worth clarifying that Box 3 initiatives to “create the future” are not student driven. The mission of theological schools is not primarily to enroll more students, but rather to enroll the right kinds of students at sufficient numbers to meet the needs of the church. Yet with students paying an increasing portion of their educational costs, and with ever more cost effective and accessible alternatives emerging, schools that ignore “student demand” factors do so at the peril of their mission.

My encouragement to seminary leaders

Take the appropriate steps that fit your school’s culture, faith community, size, and context to ensure that you are giving adequate attention to Vijay Govindarajan’s three boxes. Remember that you cannot get to Box 3 without strong initiatives and execution in Box 1 and Box 2. And take to heart the words of Mike Myatt in his new book, Hacking Leadership: The 11 Gaps Every Business Needs to Close and the Secrets to Closing Them Quickly: “A lack of innovative thinking is a precursor to a brand in decline.”

Our brands, like promises, must grow stronger, and theological schools must be capable to deliver on those promises. The church needs us. So, with God’s help, let the innovation begin!

+++++++++++

How we’re using this model at Asbury Seminary

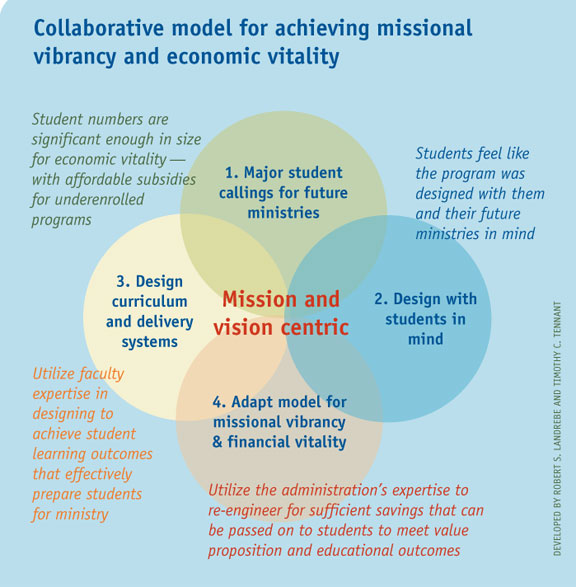

Perhaps one of the most challenging responsibilities for seminary leaders is to foster collaboration and trust in the Box 2 and Box 3 initiatives — those programs that we need to “abandon” and “create.” At Asbury, we designed the collaborative process shown here, loosely derived from the key features of the “nine building blocks.”

At the center of the design is our school’s mission and vision, but rotating round them are four commitments:

1. Major student callings for future ministries (i.e., student segments).

2. Design with students in mind (i.e., student experience).

3. Design curriculum and delivery systems” (i.e., student learning).

4. Adapt the model for missional vibrancy and financial vitality (i.e., economic model).

In order to use this collaborative design in our strategic planning work, we have identified a cross-functional team of faculty and staff to develop Box 2 and Box 3 initiatives through the use of four task forces. The task forces have been charged with providing quality input for a long-term “strategic enrollment management plan” that will envision the seminary’s future. The four task forces correspond to the four areas of commitment:

1. Student Segment Task Force

Primary objective: Develop strategic recommendations for the seminary to match the current and future needs of the church. This requires current and future student segments of significant enough size to warrant the investment of seminary resources.

2. Student Experience Task Force

Primary objective: Develop strategic recommendations for how the seminary can optimize the design and implementation of programs with students and their future ministries in mind.

3. Student Learning Task Force

Primary objective: Develop strategic recommendations and implications related to changes in degree and non-degree programs, cohort style for non-residential students, hybrid delivery model with intensives and online courses, and master teacher model with the use of instructional designers.

4. Economic Model Task Force

Primary objective: Develop strategic recommendations for how the seminary can re-engineer for sufficient savings that can be passed onto students to meet the desired value propositions and educational outcomes.

Each task force will share results on an ongoing basis with other task forces. We hope this process will let our shared governance shine, getting the best ideas from our governance stakeholders (board, administration, and faculty) and facilitating the collaboration that is essential for effective strategic planning.