Last year, Inside Higher Ed highlighted findings from a study by the College and University Professional Association for Human Resources (CUPA-HR) focusing on troubling findings: There is a stubborn gender pay gap, and women administrators make 80 cents for every dollar made by men.

We expected to find a similar pay gap among theological schools, and we did. But not in every sector.

Salary comparisons done last year focusing on differences between women and men employed at members of the Association of Theological Schools (ATS) show that women made about 94 cents for every dollar made by men, up from 91 cents 10 years ago. This is good news — the average gap is not as wide as in higher education as a whole, and the change is going in the right direction over time. These are reasons to celebrate.

At the same time, we must keep in mind that this is an aggregate figure for all schools and all levels of employment in the ATS institutional database. Aggregate comparisons, while important for noting overall patterns, can often hide underlying challenges and opportunities for conversation and change. Disaggregating the data enables us to see that parity or near parity has been reached in certain areas, but not in others.

For example, last year, on average, women in Roman Catholic and Orthodox schools made $1.11, women in mainline Protestant schools made 88 cents, and women in evangelical schools made 80 cents for every dollar made by men. These amounts are for all levels of employment and all types of schools within the ecclesial family. Keep in mind that in certain Roman Catholic schools, particularly those with connections to dioceses or religious orders, compensation levels are lower than the average for all ATS schools. The fact that some employees are priests who are paid nominal stipends is undoubtedly a factor in the impressively high $1.11 women-to-men ratio.

Disaggregation shows another disparity. Female faculty (including upper-level administrators who retain faculty status) made $1.03, and female nonfaculty made 83 cents, for every dollar made by their male counterparts. If we were to look at comparisons of women and men within these groups — for instance, administrators at the managerial and professional level and staff in support roles — we would see even more complexity.

In a recent survey of female constituents at ATS schools, we included a question about whether participants thought they were paid less than men at the same level/rank in their school. Of the 520 women currently serving in ATS schools, 40 percent said yes, 30 percent said no, and another 30 percent said they didn’t know. So we decided to check perception against reality.

First, perceptions …

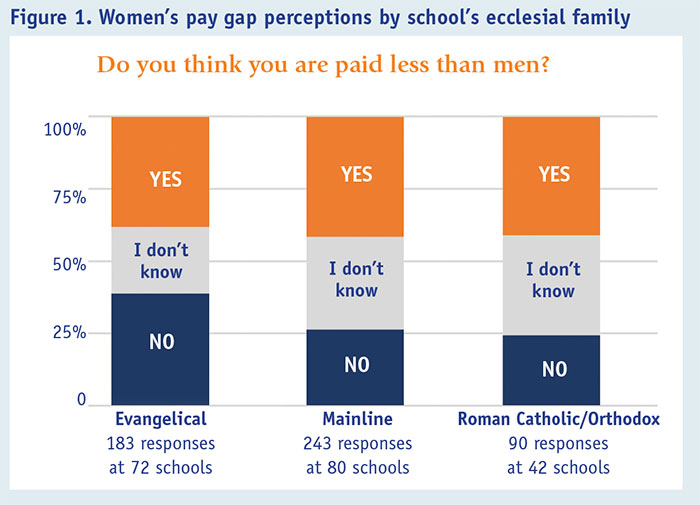

Pay gap perceptions differed by the ecclesial family of the school (see Figure 1). Responding to the question about whether they thought they were paid less than men, about the same number of women serving at evangelical schools answered no as answered yes. Of those serving in mainline Protestant or Roman Catholic and Orthodox schools, for every two who said no, three answered yes (they were paid less than men). Note that the question was worded in the negative. The larger the dark blue section of the column in Figure 1, the more positive the perception of respondents.

Many more women at evangelical schools believe they are not paid less than men at the same level/rank. This does not mean that they believe gender parity has been reached, but it may be an indicator of it. Note that the percentage of “yes” responses is about the same across the board; it is the “I don’t know” response that is significantly lower for those serving in evangelical schools.

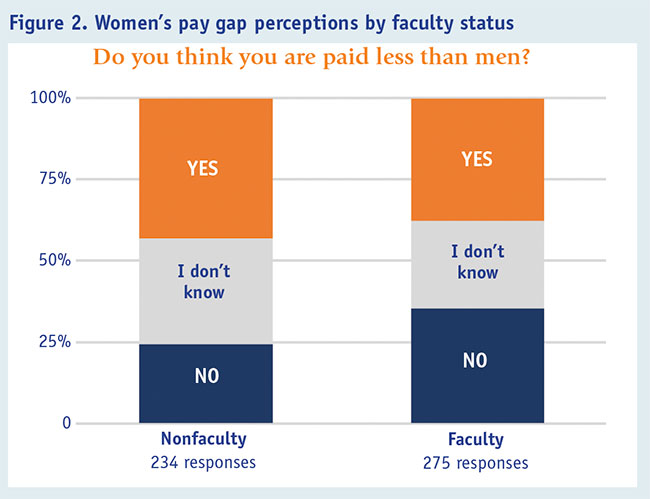

As Figure 2 shows, perceptions also differed according to whether the respondent was a faculty member. More female faculty than female nonfaculty believe they were not paid less than males at the same level or rank. Among faculty, about the same number responded no as yes; whereas, nonfaculty who responded yes outnumber the no responses almost two to one. Again, it is the number of “I don’t know” responses that is significantly different; a much larger percentage of nonfaculty were unsure.

Any comparisons made between perceptions collected in the survey and actual salaries reported in the database must be made with caution because we are not comparing per person; we are not able to identify individual respondents in this anonymous survey. However, it is interesting to note that, while perception appears to align with reality in the case of faculty versus nonfaculty, they do not align with respect to the ecclesial family of the school.

In reality …

Since 2007, the pay gap for female upper administrators has closed and moved in a positive direction — from 94 cents in 2007 to $1.06 in 2017 for every dollar made by male upper administrators in Protestant schools). The Chronicle of Higher Education last year made a similar observation: women’s and men’s salaries were closest in positions where women had the lowest representation — the top executive position. It has been suggested elsewhere that salaries have been used in higher education to recruit and retain women in roles where they are underrepresented. Perhaps this is an effective strategy that ATS schools are using to bolster the representation of women in upper leadership roles as well. Although we cannot say which came first — higher pay or more women — the same 10-year period did see a 24 percent increase in the number of women in upper-level administrator (president and dean) roles in ATS schools.

At the same time, women in other cabinet-level roles continue to make less than their male counterparts. For example, women chief financial officers of ATS schools last year made 89 cents for every dollar made by men. This is up from 76 cents 10 years ago.

Another way to look at the status of women’s pay industrywide is to consider the percentage of ATS schools where women are making more, less, or the same as men. For administrators, nearly all schools have only one person in that role (e.g., one president, one dean of students), which makes meaningful salary comparisons impossible. So in order to make apples-to-apples comparisons, we looked only at faculty (at assistant, associate, and full professor ranks). We found that, last year, 33 percent of all ATS schools had a higher average salary for female faculty, 51 percent had a lower average salary for female faculty, and 16 percent had about the same average salary for female and male faculty. (Schools with no female faculty were not included in these figures.) That women had lower salaries in half of the ATS schools may have something to do with the ranks that faculty occupy by gender, the length of service of faculty by gender, the number of faculty in each rank or tenure status, and other characteristics of the school, aspects of which could be seen as part of the culture that perpetuates existing pay gaps.

In the survey, 60 schools were identified by respondents as committed to increasing the representation of female leaders. The majority sentiment of female faculty from these schools was that they are not paid less than men. In actuality, while the difference is not as pronounced as perception, salary differences (as compared to schools not identified in this way) do appear. For these schools identified as committed to increasing female leaders, 37 percent had a higher average salary for female faculty (vs. 32 percent for schools not identified), 48 percent had a lower average for female faculty (vs. 52 percent for schools not identified), and 15 percent had about the same average salary for female and male faculty (vs. 16 percent for schools not identified). Again, to reference the strategy for recruiting female leaders in higher education, what may also be contributing to this overwhelmingly positive perception is the growth in representation of women in ATS schools: since 2007, there was a 58 percent increase in upper-level administrators among the schools identified as committed to increasing female leaders versus a 10 percent increase among the schools not identified in this way.

Concluding reflections

What can we conclude from these data? In general, the direction of change, where it can be measured, is positive. Women are increasingly well represented in senior positions and the pay gap in many instances is decreasing. But the findings about pay gaps in different sectors and about the differences between perception and reality are complicated, so care should be exercised in applying overall conclusions to individual schools.

What decisions can be made from these data? We offer a few considerations:

- Collect your own data about salary over time. To be sure, there are unique historical, confessional, political, financial, educational, and missional decisions that have shaped each school’s culture. Some of these decisions have confirmed the need for the school to maintain existing structures; other decisions have sparked necessary and productive change. In all situations, however, schools would do well to collect actual salary data and perceptions of gaps and to analyze their compensation, evaluation, and professional development strategies in order to ensure equitable salary practices.

- Disaggregate the data. Underlying inequities are often missed when data are presented only in the aggregate. It is important to slice the data into different categories of women at your school — by faculty status, rank, levels of administration, demographics, and others.

- Develop robust mechanisms for evaluating the school’s compensation strategies, regularly examine them, and communicate the processes clearly. Does your school have a mechanism to evaluate compensation? Some ATS schools, for example, have hired outside human resources agencies, established well-represented compensation committees, or published compensation schedules of salary ranges. Given the fact that situations change over time, has the mechanism been evaluated recently? Does it need an overhaul? What are the means for communicating information about compensation policies? Perceptions, whether accurate or not, also contribute to the school’s current climate and culture over time, and getting perceptions to align more closely with actual conditions requires clear communication. Greater clarity and transparency about how compensation decisions are made will be beneficial in many situations.