If you ask a theological school to tell you its mission, you might hear something like this:

- “…to prepare faithful leaders for the church of Jesus Christ…”

- “To advance Christ’s Kingdom in every sphere of life by equipping church leaders…”

- “…to be a servant of the churches of [denomination] by training, educating, and preparing ministers of the gospel…”

- “…providing, with and for the church, advanced training for strategic ministry roles.”

- “…equipping godly servant-leaders for the proclamation of His Word and the building up of the body of Christ worldwide.”

Excerpts from mission statements garnered from seminary websites.

These short, concise statements of mission help theological schools define their purpose. Most are concerned with preparing church leaders. Many include a secondary goal of preparing students for ministry “in the world” or “in every walk of life.” Seminary leaders raise funds and align programs around the vision of educating future ministers for positions of local, national, and international leadership.

But do these seminary mission statements align with what students at theological schools actually hope to do after graduation?

Fortunately, we have 17 years of data to answer that question.

The Association of Theological Schools (ATS) recently compiled data from the Graduating Student Questionnaires (GSQ) that were administered from 2001 through 2017. Our goal: To understand the vocational goals of graduates and the implication of these goals for theological education.

Expanded views of ministry

Our first pass at the data revealed that in each of the last 17 years, only about one-third of graduates anticipated serving in parish ministry — that is, as pastors, priests, or ministers in congregations.

If one of the primary goals of theological education is to prepare pastors for congregations, then these numbers should be troubling. Were theological schools not fulfilling their stated missions? Were graduates no longer interested in congregational ministry?

Next, as shown in Figure 1, we expanded our definition of ministry. We included a wider variety of vocations, including Christian educators and youth workers, hospital and military chaplains, global and local mission workers (including church planters and those working in social justice ministries), and several other types of ministry (including church administrators and musicians, pastoral counselors, and spiritual directors). Data from 2013 to the present also included associate or assistant pastor, a category added by ATS in response to the changing nature of ministry over the last several decades.

When we looked at the data in this way, we found that more than two-thirds of graduates anticipated serving in some type of ministry either within or outside a congregation.

Where else are they serving?

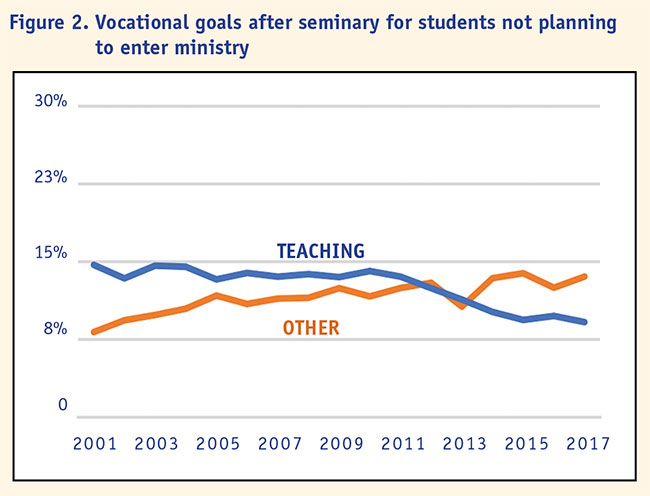

While the number of graduates anticipating serving in ministry has remained relatively stable, graduates’ other vocational goals have fluctuated over the 17-year period. For example, another core mission of most theological schools is to prepare teachers for a variety of settings, including seminaries, Bible colleges, and universities. As shown in Figure 2, the percentage of graduates anticipating going into teaching has steadily declined since 2001, with the sharpest declines in the years following the 2008 economic downturn.

While the percentage of graduates pursuing teaching has decreased, the percentage pursuing “other” vocations has steadily increased. “Other” includes those pursuing social work or social services, administration in nonprofits or for-profit businesses, medicine, engineering, law, and sales. In some cases, graduates still define their “other” vocation as ministry — for example, a nurse or doctor employed in a hospital may consider medical care to be a form of Christian ministry. In other cases, theological education helps graduates integrate faith and work, or it supports their personal spiritual growth.

What can a seminary do with this data?

Data about where graduates are serving can help boards and administrators of a theological school evaluate whether they are fulfilling their particular mission. Some of the questions that theological leaders can ask:

- If we are focused on preparing students for congregational ministry, how many of our graduates are doing that?

- If we are preparing graduates for doctoral work and teaching, how many of our graduates are actually teaching?

- If the vocations of our graduates don’t align with our mission, what do we need to adjust? Marketing? Fundraising appeals? Curriculum? Or perhaps our mission statement?

Longitudinal data on the vocational trends of graduates can help schools evaluate the impact of new programs, new curriculum, or new leadership on missional effectiveness. For example, leaders and board members may ask themselves, “If we started a social work program in 2010, has the number of our graduating students saying they want to become social workers increased since then?” And: “If we had an uptick in one area (for example, students intending to become social workers), has that been accompanied by a decrease in other areas (for example, students intending to pursue doctoral studies)?” A school may also ask, “Can we determine if a rise in social work students has shifted our school’s ethos away from congregational ministry and toward community service? If so, does this shift still meet our mission?”

Longitudinal data can also help identify emerging trends. For example, what is the long-term impact of fewer students planning to pursue careers in teaching? Will the pipeline be a mere trickle in the future when seminaries are seeking new faculty? If the percentage of graduates pursuing vocations outside of traditional ministry is growing, is that a potential new target audience for recruitment? If so, more information is needed if recruiters are to understand where graduates are working, what they hoped to learn in their theological studies, and whether they are satisfied with the education that they received.

Perhaps the most foundational takeaway from the analysis of longitudinal data is its usefulness in clarifying institutional missions. What does your longitudinal data say about your graduates? If your school’s mission is to produce graduates to work as senior leaders of congregations right out of seminary, is that reflected in your data? If a school’s mission is to form educated leaders for communities of faith and the broader public, or to develop a pipeline of people who might eventually serve in multiple ministry settings, does data from your graduates support this? Longitudinal data helps to clarify what graduates are actually doing in the world and how they are living out the mission of your institution.

All data is from the Graduating Student Questionnaire administered by the Association of Theological Schools at 65 percent of accredited institutions in the United States and Canada.