(Reprinted with permission from Commonweal, written by Lawrence S. Cunningham.)

(Reprinted with permission from Commonweal, written by Lawrence S. Cunningham.)

Kathleen Norris’s Dakota (1993) was to become an unlikely word-of-mouth best seller. I say “unlikely” because the work was difficult to classify beyond the author’s own subtitle: a “spiritual geography.” In meditative prose, Norris reflected lovingly on her life in Lemmon, South Dakota, through the lens of her long connection with Benedictine monasticism. Despite the fact that she is a Presbyterian lay preacher and a well-regarded poet, she saw nothing curious about such an oddly ecumenical approach to life.

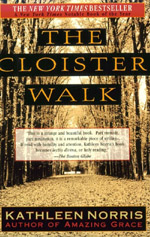

Her more recent work, The Cloister Walk, reflects her still intense connections to monasticism. She spent the better part of a year at the Ecumenical Institute at St. John’s Abbey in Collegeville, Minnesota, and her deep love for monasticism has also been acknowledged by the many invitations she receives to read to monastic communities. This book, in fact, reflects her participation in the liturgical life at St. John’s, her visits to other monastic houses, and her inevitable return to small-town life in South Dakota. It is a pastiche (some of the chapters have been previously published) of scriptural meditation and reflections on her monastic experience, along with sharply edged reflections on her own life and closely observed vignettes of the several communities within which she has found herself.

The revelatory character of Norris’s prose is best found in the fresh eye she brings to elements of the Catholic tradition that may be overly familiar to those who were born into the tradition. Our hoary reactions to virgin saints, celibacy, the misogynist streak in our ascetical tradition are “deconstructed” by the author’s angle of vision, which looks with new but hardly naive eyes. More than anything else, Norris is a contemplative reader of Scripture who follows the liturgy and reads in a manner known in the monastic tradition as lectio divina. The psalms live as poetry and the acid voice of Jeremiah (she has a splendid chapter on the latter) is heard afresh. Her reading of Scripture serves her well when called upon to preach at her own church in South Dakota.

It is one of the graces of our time that the best of our contemporary spiritual writers are women who are also poets. Among that number one must include, conspicuously, Kathleen Norris, who can bring alive the old desert fathers and mothers, the saints of the calendar, the idiosyncrasies of community, the travails of small-town living, the joys and pains of marriage and old age.

Thomas More once said that the world needed more monks and more housing for the poor. To which I would add: more poets who appreciate both those needs. Poets like Kathleen Norris who understand, as she says of Gregory of Nyssa, that “with God there is always more unfolding.”