If churches were to pool their efforts to pitch one message on billboards across the continent, that message might be "Send us young people who can lead."

|

Then I said, "Ah, Lord GOD! Behold, I do not know how to speak, for I am only a youth."

Jeremiah 1:6

Revised Standard Version |

As clergy shortages loom larger, seminarians grow older, and more and more North American congregations cling to survival, the cry for new blood to infuse vigor and rigor into pastoral ministries is on the rise. Strategies for recruiting such candidates, however, have been in short supply. The call to the aging Moses or Abraham is becoming more the norm than the call to the teenage David or Jeremiah.

Tapping the vocational longings of young men and women has required clergy who inspire youth to the ministry and congregations that cheer them on. Once nearly every major church body had a feeder system that, through formal and informal means, extolled the ordained ministry as a high calling for its young people, rejoiced when one of its own professed a "call" and proudly saw them off to seminary. Today in many of the largest denominations, that system has largely fallen apart. Rebuilding a delivery system that can encourage young people is the daunting task many churches now face. In an attempt to provide leadership that can inspire emulation, many theological schools have recently added courses and programs to develop interpersonal and practical skills. But the questions of what makes for exemplary clergy--and indeed what leadership is--remain difficult to answer.

At least striking exception exists among evangelicals. Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary shows a tight-knit recruiting pipeline still very much intact. Fully 80 percent of the 3,500-member student body is under age 30, most fresh from college. Kenneth Hemphill, president of the seminary, attributes the steady supply of young candidates to "staying in close contact with Baptist colleges and other sister schools who do quality recruiting." At secular schools such as the University of Texas, he added, Baptist campus ministries and local parishes alertly identify those seeking the ministry. "In Baptist tradition, they make decisions publicly at the church level."

Nothing has more influence, he said, than pastors who serve as mentors.

The overall picture looks far less youthful. In 1991, nearly four in ten master of divinity students (39 percent) were 35 years of age and over, according to the Association of Theological Schools. Ten years later the percentage had risen to 45 percent.

Several obstacles are blamed by church sociologists for slowing to a trickle the stream of fresh college graduates into seminaries. Among the most often mentioned are the collapse of a strong youth culture in many denominations--one that fostered ideals of ministry--and a decline in professional status of the clergy among young people when compared to such fields as law and medicine.

Behind the drop-off in younger aspirants is the apparent scarcity of church leaders who inspire young people to follow their own vocations to the ministry. Studies have shown that, for a variety of reasons, including reluctance to be too pushy, ministers and priests are often reluctant to suggest the ministry to their young people. The difficulty drawing young people into theological vocations is, then, entwined with the problem of clergy leadership.

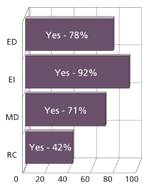

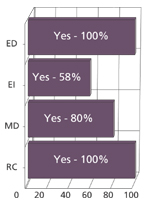

On Recruitment

We asked: Do you recruit for M.Div. candidates on a variety of college and university campuses?

You said: |

|

ED=Evangelical Denominational EI=Evangelical Independent

MD=Mainline Denominational

RC=Roman Catholic |

There is evidence that the local church is not the only garden in which future clergy can be nurtured. Increasingly, the college campus ministry has become the locus for immersion into the Christian faith and the stepping stone to seminary. Two schools as different as evangelically-oriented Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky, and mainline Lutheran Theological Seminary at Philadelphia both report a sharp upswing in candidates fresh from undergraduate colleges and universities that are mostly unrelated to churches but host lively denominational activities.

"We're getting more under 30 in the last couple of years," said Maxie D. Dunnam, president of Asbury. "It looks to me like we're exchanging second-career people for this young group. I'm hoping it's a trend. They're coming from dynamic ministries on secular campuses." Dunnam thinks the "classic Christian colleges" place too little attention on vocations. The bulk of young students, Dunnam said, are coming to Asbury from such schools as the University of Georgia, the University of Kentucky, Texas Tech, Louisiana Tech and Florida State.

Likewise, Lutheran at Philadelphia has witnessed a sharp rise in the number of under-30 seminarians, said Rick Summy, director of admissions, as the result of the enthusiasm generated by campus ministers. Whereas typically the candidate for parish ministry has been the product of a congregation, the student who comes to Christianity and to a "call" during college, said Summy, "has his or her strongest identity not with a congregation exactly but with something [on campus] like a congregation." Lutheran ministries at such places as Penn State and Indiana University of Pennsylvania provide a steady stream of students, Summy said.

Who Is an 'Effective' Leader?

Defining what it means to be an effective leader, a leader who can meet a congregation's needs, including the task of fostering potential ministers, has clearly become a huge concern among denominational and seminary officials. Often it arises out of the concerns of local congregations which want their clergy to receive more practical training in how to guide a parish successfully.

In an In Trust survey of 240 North American theological schools, an overwhelming 81 percent of the fifty-nine respondents said they had "taken specific steps to revise curriculum in an effort to bolster leadership." Courses in "leadership and administration" were among the most-often-mentioned revisions. One seminary president went on to define it as including "strategic planning, sociology of organizations, strategic financial management, resource development and leadership assessment." Another president said the aim was "leadership development for ministries of compassion and justice in a variety of institutional settings."

The widespread response to the appeals for nuts-and-bolts training from congregations and denominations signals an effort to bridge a gulf that has grown between seminaries and their parent church bodies in recent years. Part of the churches' unhappiness with the seminaries stems from a complaint that the schools were failing to prepare candidates adequately for the parish ministry. The difficulty in many theological schools is that classes in practical fields may detract from education in the classical fields of Bible, theology, ethics and history. Fully three-quarters (77 percent) of the survey respondents said they had experienced tension between trying to observe the traditional studies in the midst of the new demands.

From the survey and interviews with seminary officials in the wake of this response, a common core of desired leadership traits emerges among Roman Catholic, mainline, and evangelical Christians. Among them are an ability to preside at worship effectively, a life of prayerfulness and skillful shepherding of the congregation's affairs. In addition, the term "servant ministry" has become popular across the church spectrum much as volunteerism and "giving back" have caught hold with the public at large. As one capsule formula describes the test most Christians apply to their pastors: "Do they love God, do they love me, are they competent to do the job?"

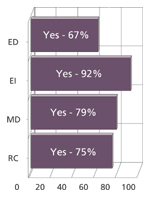

On Grade Point Average

We asked: Do you require a certain GPA minimum for acceptance?

You said: |

|

ED=Evangelical Denominational EI=Evangelical Independent

MD=Mainline Denominational

RC=Roman Catholic |

Beyond the broad agreements lie much uncertainty and confusion about what kind of leadership can bring vitality to congregations and incentive to young people. Lurking in the wings of this discussion is the corporate model. Dr. Jackson Carroll, a sociologist of religion at Duke Divinity School, refers to it as the nonprofit style by which the leader attempts to help colleagues "to discover what their abilities are."

By comparison, Carroll said, taking the helm of the congregation in his view means "being able to interpret a faith that resonates with the experience people have that promotes the vision of the church." A good leader must deal in conflict management, he added, because often congregations say they want strong leaders and may actually resist bringing in new people. "It's not simply a matter of motivating and pulling a congregation along," Carroll said. "A few are ready to be facilitated; a lot need to be pulled along."

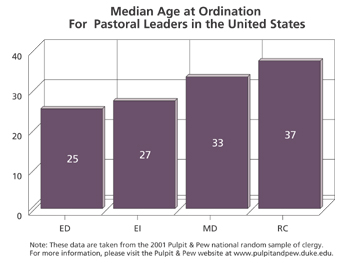

We asked: What percentage of your M.Div students are under 30?

You said: Evangelical Denominational schools had the widest range of responses (one school has 10%, another 80%), but half those schools fall in a narrow band between 40 and 55%. Roman Catholic schools, on the other hand, reported a much narrower low-high range (7-43%), but a broader middle-50% range (18-38%). One Mainline Denominational has no students under 30, while another has 56%, with most having 18-39%. Half of Evangelical Independent schools have under-30 populations of 30-52%, but one school has only 20% and another 62%.

The course titles of leadership courses are often vague, and the exact duties expected of a good church leader are rarely precise, in part because the nature of effective ministry is, by its own nature in Christian tradition, a personal gift clothed in mystery. In seminary parlance, leadership training can mean anything from supervised field-work to workshops conducted by clergy who have mastered the complexities and oddities of parish life. The connections often show pragmatism and imagination. At Lutheran at Philadelphia, for example, students are asked how the Augsburg Confession and other historic statements of faith apply to real-life situations. One problem posed the question of what this core of beliefs would say about someone in the congregation who was entering the military.

From the survey returns, the mainline seminaries appear to be placing renewed emphasis on the fundamental importance of the institution; Catholic schools are underscoring lay ministry; and evangelical seminaries have become more attuned to cultural pluralism as preparation for spreading the Word in a more diversified setting. The differences are relative, however. What stands out is that all groups have vowed to do something. Themes and strategies overlap and struggle to find their way into the curriculum. Church traditions such as a strong sacramental life or a stress on winning souls exert a powerful effect on the kind of leadership that becomes the goal. And as Summy of Lutheran at Philadelphia says, "Lots of congregations aren't as viable as they ought to be--and that raises questions in areas like stewardship and evangelism."

Heritage Theological Seminary, the training ground for pastors of the Fellowship of Evangelical Baptist Churches of Canada, illustrates the degree to which even church groups that already have a clear mission and consistent models of leadership see the need for sharpening the effectiveness of their future pastors.

Marvin Brubacher, president of Heritage, said seminarians at the school interact with a steady stream of "gifted leaders" who come to the school and oversee internships. Brubacher lists four kinds of leadership Heritage attempts to instill. One is charismatic, expressed though such activities as preaching and otherwise "articulating beliefs"; the second is visionary, helping a church plan strategies for achieving change; the third is transformational, enabling people to reach their spiritual potential; the fourth is the role of the servant, placing others before self.

A major national survey by Carroll and his team at Duke indicates the urgency of developing such skills. Initial findings from the "Pulpit & Pew" study of Christian clergy from a wide assortment of denominations found 70 percent felt they did poorly at "discerning and promoting the congregation's vision, administering the congregation's work, and training congregational members to exercise their own ministries." The report identifies all three functions as critical, along with the ability to resolve conflict (two-thirds of the respondents reported significant frictions in the previous two years), to being a successful leader.

From the evidence, it seems clear that if leaders don't believe they can do a good job of leading, young people are unlikely to find themselves excited about careers in the church. Many deterrents already stand in the way. For mainline youth, in particular, the picture can look bleak as churches shrink (50 percent or more have fewer than 100 members; a higher percentage than that in certain parts of the country), the influence of churches fades (Why climb aboard a sinking ship?); and the clergy almost invariably belong to their parents' generation or older. David J. Wood, associate director of the Louisville Institute, commented on this discouraged mood in an article in the Christian Century (April 11, 2001). In it he quoted a pastor friend:

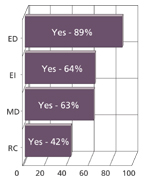

On Leadership

We asked: Does your school feel tension between a mission to provide classical theological education and a desire by local congregations for concrete leadership skills?

You said: |

|

ED=Evangelical Denominational EI=Evangelical Independent

MD=Mainline Denominational

RC=Roman Catholic |

"The reason that young people do not want to be pastors is that they see all too clearly the limitations of the pastoral life, not the opportunities ? Why in the world would a talented young person commit to a life of low salary, low prestige, long hours, no weekends, and little room for advancement?"

Efforts at Turning On the Young

In the face of such gloomy views, programs aimed raising the possibility of ministry with young people have taken shape during the past decade. Preliminary studies of the oldest of them for high school students, at Candler School of Theology of Emory University in Atlanta, indicate that these strategies may offer at least a partial remedy. Since 1998, forty-eight seminaries have received funds under a Lilly Endowment incentive to bring teenagers to campus for study, worship, and discussion of how faith applies to their life purposes. Roughly an equal number of programs will be supported at other seminaries soon.

According to Mark Winstanley, director of the Candler program, 15 to 20 percent of the 500 teenagers who have participated in it have go on to enroll in graduate theological education. Others, Winstanley said, have found the meaning of vocation in a wide variety of professions and ways of life.

A similarity among these experiments is that they bring young people together for thought, study and talk with members of the clergy and seminary professors who provide that quality of leadership distinction that has sometimes been lacking in their previous church experience. It is also a setting that allows many to talk openly and searchingly about religion with their peers for the first time in their lives. Likewise, the subject of vocation to the ministry can become an open, live option for many who had never thought of it before.

The summer routine is often a challenging plunge into the leadership provided by serious theological study. Dr. Carol Lycht, coordinator of the teen programs for the Fund for Theological Education, described a day she observed during last summer's six-week session at Duke. The morning began with prayer, continued with an interactive lecture by the noted ethics professor Stanley Hauerwaus, followed by worship. Academic, church and social activities culminate in meetings between students and mentors before lights out at 11:30.

Scattered reports suggest that these seminary sojourns have generated remarkable excitement in the young people, roughly two-thirds of whom are female. Some programs receive twice as many applicants as they can accept. But recruiting new candidates for the ministry tends to be a soft-sell in most of these programs. "The problem is that we've neglected to touch individuals to say we think you may be called to the ministry," Lycht said. "We need to do this more, being forthright about service to the church." At Catholic institutions, meanwhile, the situation is more complex owing to the church ban on women's ordination or even discussion of the subject. Young girls feeling called to serve the church can be encouraged, however, to seek lay ministries within the present structures of authority.

An equally promising venture has enlisted about 100 church-related colleges in broad-based plans to initiate the vocations discussion on campuses among students, faculty and administrators. It is also funded by Lilly: $40 million already awarded and another $50 million in the pipeline. Grants of up to $2 million have been made to a wide variety of institutions such as Wake Forest University, Earlham College and Furman University. Through these means, the institutions hope to place religion and vocation at the center of intellectual life on campus and to awaken students to new paths for their lives. Judging from the proposals, these ambitious efforts will rely on the ability of professors and officials to display a new level of leadership that can give religion greater credibility and the ministry stronger appeal.

On Leadership

We asked: Has your school taken specific steps to revise curriculum in an effort to bolster leadership skills?

You said: |

|

ED=Evangelical Denominational EI=Evangelical Independent

MD=Mainline Denominational

RC=Roman Catholic |

Some of the college programs contain the even larger agenda of helping restore a religious presence that has dimmed. The broad youth culture that once permeated mainline churches has largely disappeared, including its visibility on campus. The emphasis on vocations, some say, has the potential to bring religious people from a variety of faiths together to enhance religion's influence and to highlight the desirability of ordained ministry. Under this assumption, the infrastructure that fell apart decades ago would be at least partly restored. "We're breaking the culture of silence," said Christopher Coble, the Lilly program director in charge of the new projects. "Faculty are talking about faith with each other and with students. Most schools were floating. We've given them something to take hold of."

Simply drawing together students who have felt stirrings of faith only in isolation can liberate them. They thought they were alone, Winstanley said, and discover, somewhat whimsically, "'Maybe I'm not that crazy.' They come here and have deep relationships that continue." Example: On the first day Candler's listserve enabled former summer students to e-mail one another, a day in 1997, the volume of response crashed the system.

In some quarters, there is little apparent need for innovation, only allegiance to the tried and true. Nazarene Theological Seminary regularly harvests a bounteous yield from its network of nine church-related colleges. Seminary officials take nothing for granted, however, devoting weeks during the school year to visit the campuses to talk up vocations with faculty and students. Once at the seminary, said Dean Edwin H. Robinson, the future ministers receive "theological classics guided by practical application." The aim, he said, was "to teach them to know what the questions are. The district superintendents want our graduates to be able to lead a meeting. We care about that kind of leadership, but it's not more important than being a spiritual leader."

Source: Unless otherwise indicated, data underlying charts that accompany this article were gathered in an In Trust survey of 240 North American theological schools, 2002. There were

fifty-nine respondents.