Student learning assessment isn’t rocket science, but it is a kind of collective brain surgery: It requires a school to peer into the minds of students and determine if they are learning what the school says it is teaching.

Good student assessment shows how well a school is delivering on its mission to provide students with the knowledge, skills, and aptitudes for Christian ministry. If a seminary says, “We teach Bible, church history, and pastoral care,” it’s focusing on what is being taught. But student assessment asks about outcomes — how much have graduates learned about the Bible and church history? How improved are their skills in pastoral care?

Student assessment is a form of accountability for the seminary itself, and it’s essential.

The Association of Theological Schools (ATS) — along with other accrediting agencies — requires seminaries and theological colleges to evaluate student learning and use the results of those evaluations to improve learning levels within degree programs. Student assessment can also serve as motivation for change. As Cardinal Newman once noted, the path to holiness for an individual Christian requires constant change. Applied to higher education, change also is the path to improving the quality of teaching and learning.

Unfortunately, according to ATS, some seminaries are not meeting assessment requirements. Perhaps the evaluation of student learning seems to run counter to many organizational habits.

The heart of program-level assessment

All theological schools have a vision for shaping students in specific ways, and most describe their visions in their academic catalogs. The heart of learning assessment lies in the ability to answer two questions:

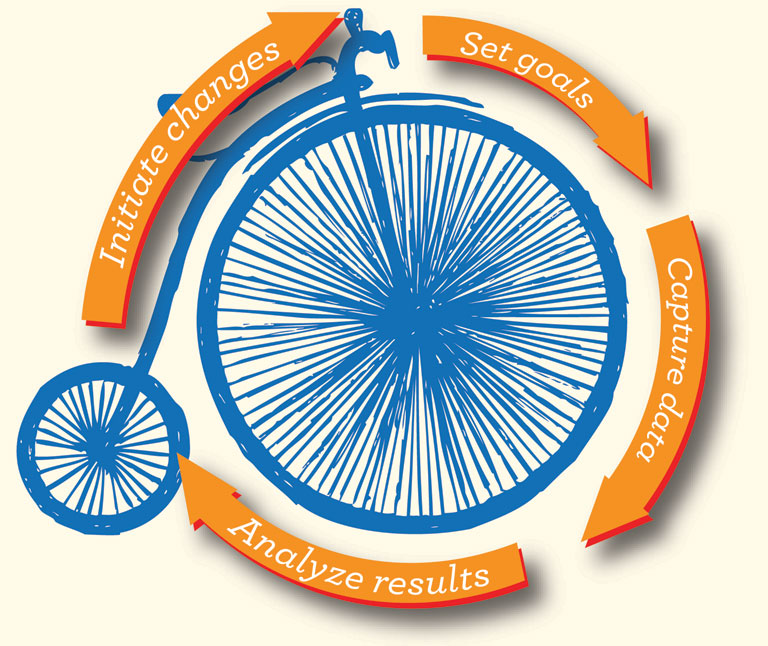

In order to answer these questions truthfully, a school must engage in a something I call a “virtuous assessment cycle.”

Phase 1. Set goals and outcomes for each degree program.

Phase 2. Use both direct and indirect measures to capture data about student performance related to these outcomes. An example of a direct measure is a juried review of a student preaching a sermon. An example of an indirect measure is the Graduating Student Questionnaire (GSQ) administered by ATS, which asks students about their growth in skills and attitudes as a result of completing a degree program. [Editor’s note: For more information on the GSQ, see "From Data to Decision" by Greg Henson, In Trust Summer 2015.]

Phase 3. Analyze the results of the data collected in Phase 2. This analysis is compiled so that it clearly relates to the program-level outcomes the school established in Phase 1.

Phase 4. Initiate changes based on the analysis of results, so future students will have the opportunity to perform better.

This cycle of assessment is “virtuous” because it is not a “make work” exercise, with the sole purpose of justifying the salaries of administrators. Rather, the virtuous cycle enables an evaluation of what matters the most to a school’s faculty: that students learn the specific things that the curriculum is intended to teach them. It is virtuous because it presupposes the possibility of learning from experience (i.e., student performance) and making changes in teaching that will help the next cohort of students learn better than their predecessors.

At the same time, the cycle only becomes helpful when a school completes each phase in order and then repeats the cycle year after year. This ongoing assessment demonstrates a commitment to constant improvement.

Schools that successfully implement the cycle evaluate key student assignments in ways that reveal mastery of several program-level outcomes at once. For example, a recorded student sermon from a capstone course in an M.Div. program may show student competency in biblical knowledge, theological reflection, awareness of audience’s life experiences, and the ability to share the Gospel in creative ways. In other words, the same assignment can be evaluated for four program-level outcomes, not just one. Such a thrifty approach to data collection and analysis makes a school able to complete the assessment cycle year after year without exhausting the scarce resources of faculty time. This lean approach makes the assessment program sustainable.

Missing the mark in assessment

Accrediting agencies consistently find that some schools miss the mark in assessing student learning. They cite three common errors.

Confusing grading with program-level assessment. Assigning students a grade for each course is a way to signal that students have passed a course, but program-level assessment takes a high-level view of the overall pattern of student learning within degree programs.

Unfortunately, some schools confuse the two. “We must be doing a good job of teaching,” they reason, “because 80 or 90 percent of students get grades of ‘B’ or better in courses. By definition, these students have learned what we want them to learn.” This misses the mark because course grades do not offer evaluators any specificity about what students have learned well or poorly. As a result, it is not possible to make changes to help future students learn any particular thing better.

Endlessly refining assessment techniques. Some schools focus on improving their techniques for assessment rather than on gathering data and making judgments based on them. Such schools report to accrediting agencies that they have changed the number of assignments directly assessed, or they have reworded survey questions used in indirect assessment, or they have refined the number of faculty committee meetings to discuss the assessment program. These schools appear to be stuck in Phase 2 of the assessment cycle.

If a would-be athlete buys new golf clubs every year but never uses them to hit a ball, that person is not a golfer. Similarly, schools that exert energy on finding the perfect survey questions or ideal set of rubrics do not move through all four phases of the assessment cycle. Continual refining of assessment techniques misses the mark for program-level assessment.

If a would-be athlete buys new golf clubs every year but never uses them to hit a ball, that person is not a golfer. Similarly, schools that exert energy on finding the perfect survey questions or ideal set of rubrics do not move through all four phases of the assessment cycle. Continual refining of assessment techniques misses the mark for program-level assessment.

Not taking action based on data analysis. Finally, some schools establish clear program-level outcomes (Phase 1), collect good data about student performance (Phase 2), and analyze these data (Phase 3), but neglect to take action to change pedagogy. For instance, a school may have a program-level outcome stating that “students will communicate effectively both orally and in writing.” After five years of data collection, the school may learn that two out of five students struggle to make coherent arguments in academic papers. If the school holds faculty meetings to discuss the problem but the faculty make no changes in instruction to help students make better arguments, this school has not completed the assessment cycle.

Accrediting agencies don’t expect schools to make expensive, complicated changes based on assessment results—it’s not necessary to create a campus writing center and staff it with newly-hired writing teachers. Rather, agencies look for modest changes such as redesigning assignments and providing more coaching for students. For example, a professor might change a 30-page “term paper” assignment into three smaller assignments: an outline, a one-page summary of the paper’s thesis, and the finished document. Faculty feedback on the outline and summary may improve a student’s ability to write and submit a final paper that meets the professor’s standards. Strategic small changes in instruction can lead to improved student performance.

In the final analysis

Accrediting agencies want to see theological schools go through all four phases of the assessment cycle. Schools then can answer the key questions: How well have students learned what the catalogue promises that they will learn from the faculty? And how is instruction being modified so that learning improves?

Accrediting agencies are not alone in wanting to know the answers to those questions. Since theological education matters so much, we’re obligated to do it well. Assessment is the best way to determine the success of our programs, and to ensure that we improve them for the students — and the church — of the future.