Not all board members are savvy when it comes to crunching numbers. But a seminary can’t achieve its mission without strong financial leadership, and the whole board is responsible for the school’s economic vitality, even if they don’t sit on the finance committee.

Not all board members are savvy when it comes to crunching numbers. But a seminary can’t achieve its mission without strong financial leadership, and the whole board is responsible for the school’s economic vitality, even if they don’t sit on the finance committee.

Below are four gutsy ways that chief financial officers can help boards and senior staff members make wise bottom-line decisions.

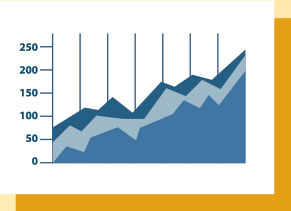

Track net revenue per student across time

It takes moxie for a CFO to dampen a board’s euphoria by showing how an increase in tuition, or even a bump in enrollment, can make costs rise and net revenues dip. For example, if you raise the sticker price of tuition, but increase student aid by the same amount, there’s no net gain from the increased tuition. Similarly, if you can rent out your campus apartments on the open market for a higher rate than students pay, then each new on-campus student is costing you extra. In sum, if you are losing money on every student, then more students = greater losses.

Keep deferred maintenance front and center

Once I knew a board that designed a successful campaign to upgrade campus buildings — but that was literally one time. Everyone knows that it’s hard to raise funds to maintain older buildings. That’s why every year schools should spend a minimum of 2 percent of the replacement value of the campus to keep the physical plant in good order. Too often schools delay maintenance because it’s easy to do, and nobody notices until a boiler dies or a wall buckles. The tough CFO reminds the board at every meeting of the need to allocate funds for bricks and mortar renewal. Even if it can’t be squeezed into this year’s budget, the board needs to stay aware of the dollar amount of maintenance being further deferred.

Once I knew a board that designed a successful campaign to upgrade campus buildings — but that was literally one time. Everyone knows that it’s hard to raise funds to maintain older buildings. That’s why every year schools should spend a minimum of 2 percent of the replacement value of the campus to keep the physical plant in good order. Too often schools delay maintenance because it’s easy to do, and nobody notices until a boiler dies or a wall buckles. The tough CFO reminds the board at every meeting of the need to allocate funds for bricks and mortar renewal. Even if it can’t be squeezed into this year’s budget, the board needs to stay aware of the dollar amount of maintenance being further deferred.

Put the budget in context

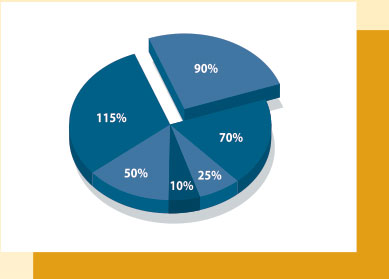

It’s critically important for a board to see next year’s budget as part of a continuum that includes actual annual results from the three previous years and projections for the next two or three years. The past and present financials should be presented in detail, and the projected budgets should take into account likely trends and possible changes. This continuum tends to flush out wishful thinking. If enrollment for the last three years has been flat, but this year’s budget predicts an enrollment increase of 40 students, and next year’s predicts 60 more, a board member might ask for a reality check: “What’s going to make that happen? Who are these new students and where are they coming from? What will it cost us to get them here? What resources will it take to educate them?”

It’s critically important for a board to see next year’s budget as part of a continuum that includes actual annual results from the three previous years and projections for the next two or three years. The past and present financials should be presented in detail, and the projected budgets should take into account likely trends and possible changes. This continuum tends to flush out wishful thinking. If enrollment for the last three years has been flat, but this year’s budget predicts an enrollment increase of 40 students, and next year’s predicts 60 more, a board member might ask for a reality check: “What’s going to make that happen? Who are these new students and where are they coming from? What will it cost us to get them here? What resources will it take to educate them?”

Strike the right balance

CFOs do more than balance the budget. They also strike a tenuous balance between being Dr. “No” and rubber-stamping every pie-in-the-sky idea floated by a board member or senior staffer. It’s critical for a CFO to think of him- or herself as a partner of the president. The CFO needs to model the president’s dream in hard facts and run the numbers to determine if the dream is feasible.

The challenging part comes when the CFO must deliver the news that an idea can’t be pursued for financial reasons. My best advice to a CFO in that situation: Never say, “No, we can’t do that.” Instead, because you have access to all of the puzzle pieces, do an analysis and explain the repercussions of the idea. Then you can honestly say, “Your idea looks like it doesn’t have a sustainable outcome, but I like the way you’re thinking.” Then propose an alternative: “What if we did it this way instead?”

The challenging part comes when the CFO must deliver the news that an idea can’t be pursued for financial reasons. My best advice to a CFO in that situation: Never say, “No, we can’t do that.” Instead, because you have access to all of the puzzle pieces, do an analysis and explain the repercussions of the idea. Then you can honestly say, “Your idea looks like it doesn’t have a sustainable outcome, but I like the way you’re thinking.” Then propose an alternative: “What if we did it this way instead?”