|

|

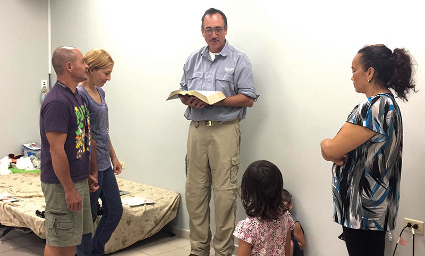

Volunteers from Princeton Theological Seminary and a local repair team in the chapel of the Evangelical Seminary of Puerto Rico. President Doris García Rivera stands in the center of the back row.

Credit: Victor Aloyo

|

For seminaries in Puerto Rico, recovery from Hurricanes Irma and Maria has proven to have layers of meaning. It’s the immediate rebuilding needed to get classes up and running, roofs repaired, libraries reopened. It’s humanitarian assistance: being a spiritual and physical presence for those in deep need, who’ve lost their homes and jobs and sometimes their hope. And it’s looking ahead to the future of theological education on the island, investigating the role of seminaries in training pastors who minister to those in need and who raise up issues of systemic injustice.

The physical recovery

Last September, Hurricanes Irma and Maria left homes and businesses flattened. The storms washed away roads and forced millions of Puerto Ricans into survival mode, struggling without adequate food, shelter, water, or electricity.

Leaders of the Evangelical Seminary of Puerto Rico, a Protestant theological school in San Juan that is affiliated with six denominations, were determined to resume the first semester’s classes despite the difficulties, says Palmira N. Ríos-González, acting dean of academic affairs.

Because of damage to the seminary’s buildings, the administration relocated classes to a temporary space at another school, and the faculty began teaching without electricity, changing the schedule to hold all classes in the daylight. “People worked very hard to make sure we could continue the first semester,” Ríos-González says. Even after the electricity was restored, “there were many blackouts.”

The spring semester brought more rebuilding. The seminary’s library, with a historic, 99-year-old collection of theological documents, is being restored, in part with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities. And phone service is “slowly coming back,” says Ríos-González.

“As long as the transportation system remains damaged here, it is difficult for our students, who come from all over the island,” she says. “In some areas, roads are damaged and traffic lights are not working.” Many students face crises in their own congregations, families, and communities. “It is a very challenging time for our students.”

The Inter-American Adventist Theological Seminary also suffered physical damage from the storm, but its academic schedule was largely unaffected. The seminary offers classes at multiple campuses across Mexico, the Caribbean, and Central and South America; at the Puerto Rico campus, most classes are summer intensives held in June and July, so there has been time to repair before classes resume.

The Adventist seminary’s property in Mayagüez, on the western side of the island, took a physical hit from the winds, including damage to the roof and to the seminary’s book collection, says Efraín Velázquez, the seminary’s president. Testing revealed that, because of water damage, the walls between some of the offices were full of mold.

The Adventist church has been very supportive in providing funds for the repairs, Velázquez says. “We don’t have to do fundraising” or rely on government assistance, he adds. As a result, “it was a great opportunity for us to do service.”

The humanitarian response

Velázquez lives about an hour from the seminary, in northwest Puerto Rico, near where Hurricane Maria departed the island and where the Guajataca Dam was in danger of failing.

Within the first 24 hours after Maria, “I went to the shelter because I knew many people from my church were there,” says Velázquez. What he encountered first was fear. “I spent a couple of nights there at the refugee compound. People were scared,” worried about what would happen to their homes, their jobs, their families. “But at the same time, I saw a lot of resilience. People were very resourceful. They were not waiting for the government to come.”

|

|

Efraín Velázquez, president of the Inter-American Adventist Theological Seminary, performed a wedding in a refugee center in the days following Hurricane Maria.

Courtesy Inter-American Adventist Theological Seminary

|

Coincidentally, Velázquez had been in New Orleans when Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005, helping his mother who was in the hospital preparing for a liver transplant. As a result of what his family experienced during Katrina, Velázquez planned ahead for what might happen someday in Puerto Rico: stocking up enough food and water for two months and installing a diesel generator and two 800-gallon cisterns.

After Maria, his secretary’s home was filled with five feet of mud. She and her husband, a retired pastor, moved in with his family for two months — one of a group of seven families who took shelter in his home.

Velázquez began driving to nearby areas, to check on people and bring what supplies he could, some of which were donated by churches in the United States.

“This was really an adventure,” he says. “Sometimes the streets had collapsed,” the roads eroded. “We had to be careful of the cliffs.”

Velázquez saw children using chain saws. People were crying and praying amid the devastation. He stayed overnight with an elderly man who “was just too frail to move” and who died about two weeks later.

Many seminarians in Puerto Rico already serve churches, and they were on the front lines of the response, says Ríos-González, the acting dean at the Evangelical Seminary. “Too often our churches and religious organizations were the ones reaching out to communities to assure their basic needs,” rather than the government, she says. “Our churches were working very hard under very difficult circumstances to reach out to the most vulnerable, to the needy, to the elderly. There are too many elderly who are alone in Puerto Rico. Their families have left.”

According to Ríos-González, when representatives from the churches delivered food and water, sometimes weeks or even months after the storm, people often said to them: “You’re the first one who’s come to help us.”

In the aftermath, the seminary’s leaders have tried to expand pastoral care, talking to students and faculty about what they had experienced and about their own losses and pain. “These were very personal and emotional” conversations, Ríos-González says. “For people of faith, it is very difficult for them to acknowledge that they too are suffering.”

But there have also been flashes of beauty and hope.

“It was beautiful to see Catholics, Pentecostals, Presbyterians, and Adventists just working together without any concerns,” collaborating without worries about doctrinal differences, says Velázquez. He performed a wedding at a refugee center, seeing love triumph in the rubble.

“I have so many stories,” he says. “I just have to praise God for what He has done.”

The work crews

Starting early in 2018, seminaries in the United States began sending work crews to help with the rebuilding.

Victor Aloyo, the associate dean for institutional diversity and community engagement at Princeton Theological Seminary, a Presbyterian seminary in New Jersey, went in December to meet with representatives of the Evangelical Seminary and of El Guacio, a Presbyterian camp and conference center in San Sebastián, to learn firsthand what the needs were. Then he crafted an action plan.

Earlier this year, a team of skilled workers from the Princeton Theological Seminary community traveled to the Evangelical Seminary of Puerto Rico where they made repairs to the chapel, installed new lighting in the classrooms, and renovated the entrance to the administration building.

Credit: Victor Aloyo |

Princeton Seminary’s annual book sale, held during the second week of October, has traditionally been used to construct or amplify the libraries of theological institutions, often in developing countries. After Maria, the decision was made to send the funds to help with rebuilding the seminary and library in Puerto Rico and also to send work teams, to get some “hands and feet on the ground,” Aloyo says.

The purpose of that trip, which he made with German Martinez, Princeton Seminary’s director of facilities and construction, and Cathy Cook Davis, associate dean of student life, was to hear directly from the Puerto Ricans what the most urgent needs were.

Next, a nine-person work team traveled to the island from January 27 through February 4 — a team of skilled workers, including roofers, plumbers, carpenters and electricians. By night, they slept and ate at a Presbyterian church in Bayamón; by day, they worked at the Evangelical Seminary. They repaired floors, windows, and ceilings in the chapel; restored the classrooms and installed new LED lighting; and renovated the entrance to the administrative and academic wing.

The work crew donated all the materials they used, shipping some supplies ahead — including a transfer switch necessary to connect a much-needed generator — and buying other material on the island. They also made a donation to the host church, to cover their costs for meals and lodging.

Another group plans to go to the island in October, this time including six seminary students, six skilled workers, and three people trained in pastoral care.

The diaspora

As Puerto Rican seminaries look ahead to the future, one financial and spiritual reality is that Hurricane Maria added exponentially to the island’s economic difficulties and has accelerated the migration of many Puerto Ricans to the mainland.

Aloyo spoke to members of the seminary community who told of deaths among their own families and friends following the hurricane. Schools have been shut down, costs are high, and some seminarians have lost their jobs. Some “are wrestling with staying in Puerto Rico or going to the States to take care of their families,” says Aloyo.

Ríos-González indicates that an ongoing challenge is the “massive migration of Puerto Ricans to the United States as a result of the hurricane,” and of economic policies that are constraining needed social services. It’s estimated more than 100,000 Puerto Ricans have left since Hurricane Maria slammed ashore. For many, those departures may be permanent.

On the island, conditions remain difficult, and the Evangelical Seminary’s finances are tenuous. After the hurricane, shortages developed and the prices for food and materials needed for rebuilding shot up. With congregations hit hard, students who are already serving churches can’t afford to pay their tuition, according to Ríos-González.

“I am hoping that as we are able to continue our classes, our students will be able to stabilize their situations and be able to come back,” she says. “We really need financial aid for our students. Many of the denominations are not in the situation to support all of their candidates as they were able to in the past.” She says that they need to raise funds both for tuition and for living expenses.

The Evangelical Seminary of Puerto Rico had an enrollment of about 230 in the second semester, but enrollment may drop soon. “Many families will wait for the school year to end to leave,” Rios-González says.

The futureDespite the difficulties, seminary leaders look ahead with hope.

The Adventist seminary is moving ahead with a plan for construction of its new facility, with offices and classrooms, which was already in the works when the storm hit — a $2 million project Velázquez hopes will be completed by the summer of 2019. The seminary hopes to begin offering a doctoral program in Spanish by 2020.

With the construction project — which will be part of the Antillean Adventist University campus in Mayagüez — “permits are an issue,” with speculators and a trade war driving up the cost of steel, Velázquez says. “Politics have been worse than Maria for us.”

Both the cost estimates and the architectural plans also have changed as a result of the storm, including adding fewer windows and using glass that can sustain winds of 175 to 200 miles per hour.

There also are opportunities to build new alliances. Princeton Seminary, for example, is exploring the opportunity of developing a January term course in Puerto Rico, enrolling students from both Princeton and the Evangelical Seminary.

There has never been a more important or difficult time for theological education in Puerto Rico, says Joanne Rodriguez, director of the Hispanic Theological Initiative, an organization that offers mentoring and other support to Latino graduate students in theology. With few seminaries on the island, “there are not a lot of opportunities for theology scholars to return to Puerto Rico and find jobs.”

Aloyo believes that with so many Puerto Ricans leaving the island and with a growing Hispanic and Latino population in the United States, seminarians need training in intercultural work. As Puerto Ricans make new lives far from home, “we as people of faith must support and accompany those brothers and sisters,” Ríos-González says.

According to Ríos-González, the faculty at the Evangelical Seminary also has been sustained by making space for critical thinking in difficult times.

Following Maria, an entire edition of the Evangelical Seminary’s journal focused on “how to reconstruct faith after the hurricane,” she says.

Continuing migration leaves the most vulnerable people behind on the island, Rodriguez says. “Right now there’s a need not just for rebuilding structures, but helping people have hope. There are high rates of depression going on in Puerto Rico right now — anxiety, ideas of committing suicide because of the devastation and the help not coming. Sometimes in these difficult situations, people come up with new theology that is important for people to take on, an understanding of suffering and hope. We need both.”

At the Evangelical Seminary, scholars are discussing the responsibility of Puerto Rican theologians and pastors to address systemic inequality, says Ríos-González.

“It is now becoming more urgent than ever that we address inequality and the high levels of poverty in Puerto Rico,” she says. “It was there before Maria. It was there before Irma. Too often people deny or ignore it. Now we see it. We are people of faith, and we need to try to transform this inequality.”