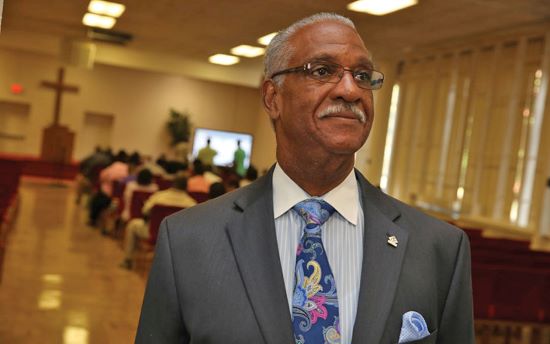

Courtesy Interdenominational Theological Center

You are not a leader if nobody is following you. You cannot lead if you are so far ahead of the people you are leading that they cannot see you. And you cannot lead if you are behind everyone else.

Dr. Gardner C. Taylor made these statements during a preaching class I took at Colgate Rochester Divinity School in 1970. I do not know if they were meant to be profound, nor if they originated with him. However, they had a profound impact on me at the time, and they have continued to affect my thinking and leadership style.

I do not have any critical or unique insight into the art of leadership. I have not studied leadership as an academic discipline and I have not read widely on the subject. Instead, the insight I bring comes from the reality of my experience. For most of my life, I have been a leader, whether this happened intentionally or whether I was thrust into the role. Because of this, I have found myself musing about how one becomes a leader. Are they born or are they made?

What follows are some insights that I have recently been reflecting on:

1. Leaders are born and leaders are made.

I believe that God gives some people the gift of leadership. That is, they are born with personalities that attract others. Perhaps it is their ideas that draw people to them, perhaps they have a way of encouraging and affirming people, or perhaps they have courage and strength of character. Like any gift from God, the ability may come naturally, but when it is exercised and used with the tests that are part of leadership, over time, the skill can mature and develop.

I also believe that leadership skills can be developed by people who are not natural leaders. Introverts who find it difficult to be with other people, those who are not compassionate by nature, and those who hate speaking to crowds can all become excellent leaders. It may be more difficult for them, and they may need to make adjustments, but it is entirely possible.

2. Leadership, and the skills needed to lead, are in and of themselves morally neutral.

Leadership can be used benevolently or malevolently. Because leaders are human, they often blur the lines between these two extremes. Even the best leaders can make terrible mistakes that destroy lives, and the most heinous leaders are capable of benevolent acts that have a positive impact on people.

This is not how people like to think about leaders and leadership. We like the lines between good and bad to be clear and distinct, but life has taught me that there are many shades of gray. It’s better to evaluate the qualities of a leader over time than to form a judgment based on one particular act, regardless of whether we believe that act was grace-filled or demonic.

3. It is essential to cultivate leaders who have a moral compass.

Even persons with strong moral values can make serious mistakes, but when confronted with their errors, they don’t persist or repeat them.

People who lack a moral compass and who allow themselves to be the sole determiners of good and evil will continue to make decisions based on self-interest. Over time, this proves detrimental to the wider human community. Yet even the most demonic leaders in the world may demonstrate leadership skills. It’s possible to be an “outstanding leader” with a moral compass that is out of sync with truly moral values.

4. Effective leadership is difficult and requires courage.

Sometimes leaders must stand alone and make difficult decisions that are misunderstood by, and may alienate, friends, supporters, and followers. However, leaders who have done the work needed to inform their decisions are obliged to do what must be done, no matter the personal cost. That takes courage.

It may mean charging into enemy fire or retaining all of the company’s employees despite the advice of the CFO. It may mean remaining silent when under public attack to protect the reputation of the institution and individuals who would suffer unfairly if the leader were to break the silence for face-saving explanations.

5. True leaders own their mistakes and do not allow Monday morning quarterbacks to undermine their self-awareness or confidence.

It takes great courage to make important decisions, and to take responsibility if decisions turn out to be wrong. Leaders are human and they will make mistakes even when they have done all they could to make the right decision.

Many of the lessons I have learned about and from leadership came from painful experiences.

I have been blessed to be a leader. I do not claim to know all I need to know to be a leader. Indeed, I continue to find myself wondering about my role. Because I have often been thrust into situations in which I was the first African American in a particular role, I have not had many mentors. So I’ve learned from watching others at a distance, trying to figure out what I needed to do. And, of course, I have learned by making mistakes.

Benjamin Franklin wrote in Poor Richard’s Almanac: “Experience keeps a dear school, but fools will learn in no other, and scarce in that.” I bear on my body and spirit the marks of mistakes I made as a leader. I also bear others that I got when I dared to do the right thing.

6. One of the greatest gifts of leadership is the ability to help others recognize their gifts and provide space for them to develop those gifts.

A mutually respectful relationship with those you lead, and an appreciation for collaboration whenever possible, allows for both individual and institutional growth. As a leader, there will be times when expectations must be clarified and corrective measures implemented, but the goal is always improvement so that both individuals and organizations may fulfill their potential. This is, after all, what leadership — benevolent leadership, moral leadership — ought to aspire to.

An earlier version of this article appeared in the February 2019 issue of ITC Now, the newsletter of the Interdenominational Theological Center in Atlanta.