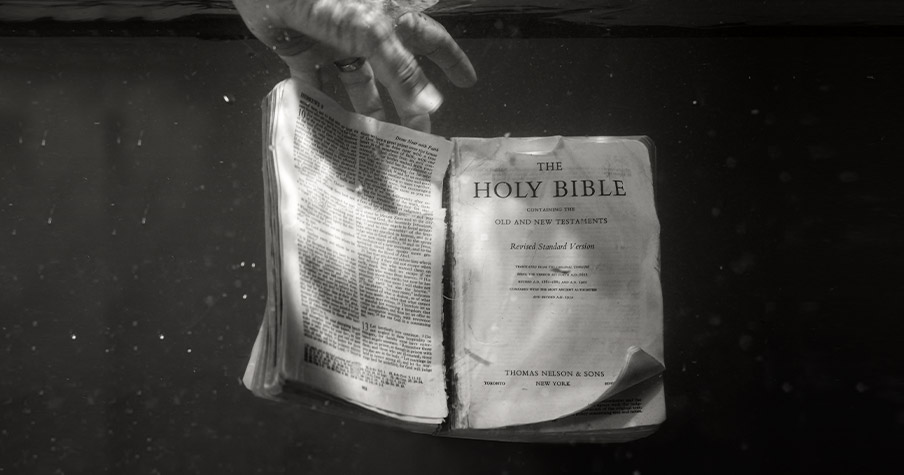

Photo illustration by Thomas Allen

In Trust magazine’s partnership with the Theological Education Between the Times project continues with the publication of an essay by Daniel Aleshire, Ph.D., the retired president of the Association of Theological Schools. It is drawn from his book for the series, Beyond Profession: The Next Future of Theological Education.

Between the Times is based at the Candler School of Theology of Emory University and funded by Lilly Endowment, Inc. Gathering diverse groups of people for conversations about meanings and purpose, it begins with the understanding that theological education is undergoing profound change, and aims to stimulate conversations about the ends of theological education that can orient later conversations about its means.

This coming fall, most theological schools will be looking back on more than a year’s efforts of adapting to distance learning and socially distanced in-person education, celebrating commencements and convocations remotely, working to keep finances stable, and recruiting prospective students with limited foresight to assure them about what, exactly, their education would look like when they have enrolled. Few think that the theological education practices in the coming academic years will return to what they were before the pandemic. What, then, will be the future of theological education?

Before the pandemic began, I finished a book, Beyond Profession: The Next Future of Theological Education, about what I think should be the future of theological education. It has been published just as hopes are building that the death, illness, and isolation that the pandemic has wrought may subside. Would the book have argued a different thesis if I had known two years ago what I know now? Are lasting changes caused by the huge, rogue wave of a pandemic that has washed ashore, and ravaged lives and property? Or, are the most durable changes the result of strong currents that are less visible but even more powerful? I choose the latter.

Across the centuries, theological education has been deeply influenced by three social forces, like deep and powerful currents. The first is the culture in which ministers and priests have been educated. Culture is not determinative, but it is profoundly influential. In the colonies, theological education contributed to the formation of what was to be the culture of a young nation, and over time, the culture itself became an influencer of theological education.

The second social force is higher education. Seminaries are special purpose higher education institutions. Theological education helped form higher education in the colonies, but over the ensuing years, higher education – like culture – has profoundly shaped the structures and practices of theological education.

The third and perhaps most significant influence on theological schools is the church – the religious communities for which theological schools educate students and advance religious understanding. As the church changes, theological schools have changed in response.

After the tidal wave of the pandemic finally washes out to sea, these three currents will continue their unseen but unreleting influence on theological education.

After the tidal wave of the pandemic finally washes back out to sea, these three currents will continue their unseen but unrelenting influence on theological education. The culture is secularizing, and theological schools will not be able to resist that influence. Higher education, perhaps for the first time in American culture, has lost some of its cultural luster, and the credibility theological schools once enjoyed as higher education institutions will wane as well. The church, as everyone knows and comments on, is changing. Denominations are less robust as organizing vectors in North American Christianity than they once were, less able to attract loyalty, and no longer able to support many of the institutions they founded. While many congregations are stable or growing, others are weaker. Religion remains strong and vital, but it is changing. The next future of theological education will be profoundly influenced by these changes. How should it change?

The present cultural and religious moment is calling theological educators to accept more responsibility for attending to the characteristics that Christian ministers and priests will need in coming decades. These characteristics are quite ancient – “temperate, sensible, respectable, hospitable, an apt teacher, not a drunkard, not violent but gentle, not quarrelsome, and not a lover of money” – as they are enumerated in the Pastoral Epistles. Along with being “a lover of goodness, prudent, upright, devout, and self-controlled… (with) a firm grasp of the word that is trustworthy…,” the qualities authorized religious leadership in a culture that was adversarial to the Christian project, when congregations were more likely to gather in homes than in stately buildings, when the church proclaimed its faith to friends and neighbors who had never heard of it.

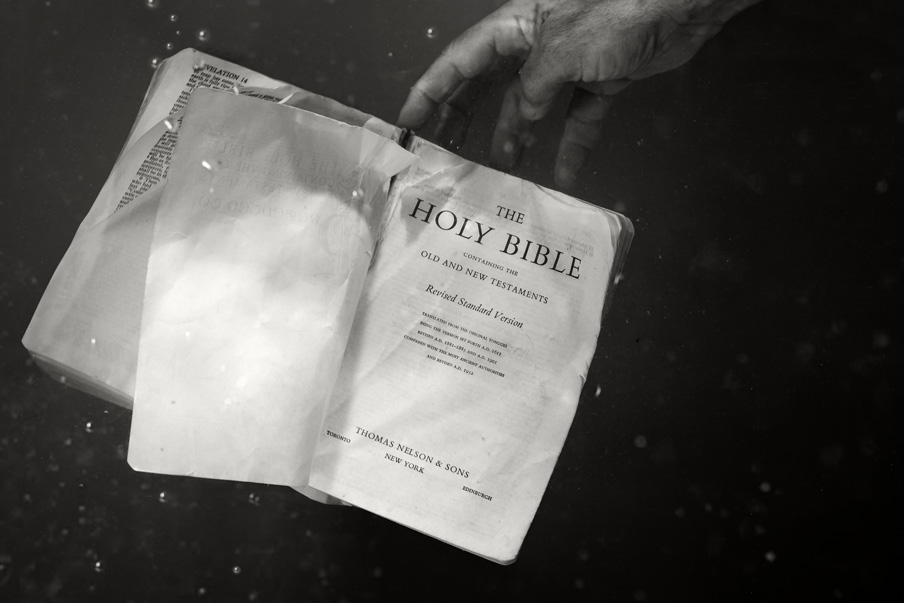

Photo illustration by Thomas Allen

Theological education has had many futures, and I think its next future will require patterns of education that are as intellectually rigorous and pedagogically sophisticated as present ones, and also will incorporate a wider vision of educational aims and purposes. It should continue its attention to the content of theological studies and the skills needed for ministerial leadership while giving increased attention to the spiritual, moral, and relational character of Christian life. It is not as if no attention has been given to these qualities. Many schools are giving them increased attention, but more needs to be done by locating them more centrally in the curriculum and developing the pedagogical practices that will contribute to their cultivation. Good theological education has always been formational; the next theological education will need to be even more intentionally formational.

I finished writing this book 50 years after I entered seminary. I grew intellectually as a seminary student as much or more than I did in a Ph.D. program. I cherished the years that I was a professor at a seminary working with students and the years that I was an administrator at the Association of Theological Schools working with presidents, deans, and faculty. The professional model of theological education I received was right for me personally and right for the church and its location in the culture.

The proposal I am forwarding does not emerge from a sense that theological education has been done wrong or that something is broken and in need of repair. The times, however, are changing, and the professional model of theological education will not be as good in the next century as it was in the last one. Theological education, if it is to be as good for the future as past versions were for an earlier day, must change. And that change will require a formational theological education that expands the canvas on which education of ministers and priests is painted.

Some people want to get rid of all the furniture of theological education and start over while others want to refinish a few pieces and keep everything just as it is. Maybe, just maybe, the task the future will most need will be to go to theological education’s attic and retrieve things put in storage that had stopped being used, even though their usefulness was undiminished.

Formational theological education involves retrieving the qualities that the early church saw as crucial for its leaders, incorporating them into the goals of theological education, and modifying the practices to place greater focus on these characteristics. The future will require all the study of text and tradition that the professional model has provided as well as all the skills that are currently being taught, but it will also require theological education practices that cultivate moral maturity, relational integrity, and spiritual maturity. These changes will make theological education different in subtle but profound ways.

As my career in theological education closes, I find myself simultaneously experiencing an old beginning and a new one. The old one is memory of the goodness of theological education as I experienced it, and the new one is a confident hope that the next theological education will be as right for its time as the last one was for my time.