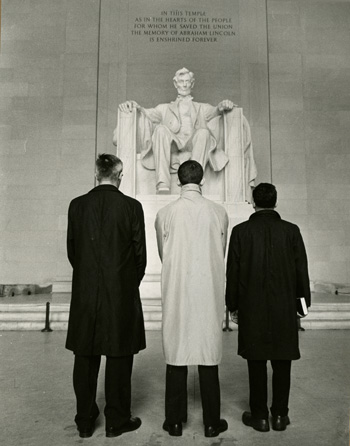

For two months in 1964, seminarians kept an around-the-clock silent vigil to support passage of the Civil Rights Act. Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary

Recent protests against the Gaza war at U.S. universities disrupted classes and commencement ceremonies and resulted in thousands of arrests. Media coverage compared the turmoil of these protests to that of the free speech and Vietnam protests on campuses in the 1960s and ’70s. But an earlier demonstration, led by theological students, offers a different example of how students have pushed for change.

On April 19, 1964, the Theological Students’ Vigil for Civil Rights began a silent, around-the-clock presence outside the Lincoln Memorial to support passage of the Civil Rights Act, introduced to Congress nearly a year earlier by President Kennedy. The bill faced fierce opposition from some lawmakers and was at that point ensnared in a filibuster in the Senate.

Jude Molnar, a Franciscan seminarian studying philosophy and theology at Catholic University of America, explained the vigil’s origins in a May 9, 1964 story in The New Yorker. “The idea started in New York, among the future ministers at Union [Theological Seminary],” he said. “They simply crossed the street and enlisted the future rabbis [at Jewish Theological Seminary], and then they invited the candidates for the priesthood down here to join them. Now more than 75 seminaries, all over the country, are participating.”

In a predominantly Black neighborhood in Washington, the Catholic Church of the Holy Comforter opened its doors to the group and became its center of operations. The New Yorker story describes the scene there. “We...found a number of young men, some in clerical collars, others in jackets and ties, arriving, leaving, sleeping on rubber air mattresses, or engaging in animated conversation.” A sheet of instructions posted on a bulletin board read: “Students should stand in silence facing the monument. At midnight the group leaving the vigil should spend a few minutes standing directly before the statue of Lincoln. We are not promoting, debating, or pushing, only witnessing. This is basically a silent prayer vigil....” Next to the instructions was a schedule for the next few days, with all slots filled and a list of alternates available if needed.

Each three-hour shift was covered by a minimum of three seminarians – one Protestant, one Catholic, and one Jew. Sometimes more students kept vigil, and sometimes administrators took a shift; they included Union President John C. Bennett; Jewish Theological Seminary Provost Bernard Mandlebaum, and George Dunne, assistant to the president of Georgetown University.

One student, Jonathan Levine of Jewish Theological Seminary, was quoted in The New Yorker after a late-night shift: “I don’t know how much this demonstration is going to accomplish for civil rights, but I know what it’s doing for us,” he said. “The exchange of ideas is marvelous, and I think that we’ve all made some friends for life among people we might otherwise would never have met.”

The vigil-keepers had some impact on civil rights – the compromise bill passed the Senate on June 19, two months after the vigil began. This July 2 marks 60 years since President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Verbatim

“It was the most challenging ministerial assignment I’ve had in almost 58 years—and also the most rewarding.”

—Robert Smith Jr., the Charles T. Carter Baptist Chair of Divinity at Beeson Divinity School, on reading the Bible for a new audio version of the English Standard Version, released by Crossway in March.